During the wave of 1970s activism that produced the occupations of Alcatraz, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Wounded Knee, Indigenous people learned the power of media to convey their message to the world. The first Native film festivals emerged to present nascent Native moviemaking. From a start in San Francisco in 1975, these conclaves have burgeoned into major forums allowing Native peoples to tell their own stories in their own voices.

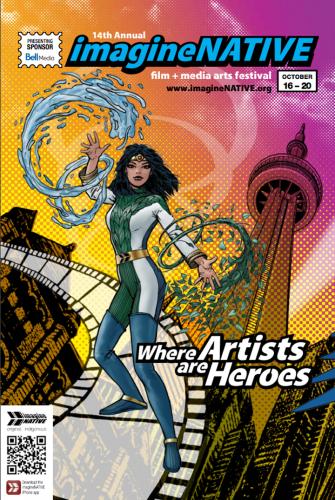

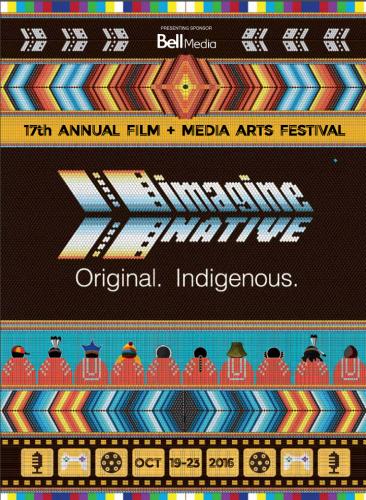

The major showcase is now the imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival in Toronto, Ont. Now in its 18th year, it presented more than 115 film and video works from 16 countries in a five-day run in October. Artistic Director Jason Ryle (Salteaux) says, “These works need to be seen, and oftentimes our festivals are really the only one presenting this work.”

Festivals this year are strongly engaged with current issues like the wave of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada and elsewhere. In fact, this season has been called the year of women’s empowerment. More than half of the films at this year’s Native Cinema Showcase in Santa Fe, N.M., this August were by or about Native women. At the imagineNATIVE festival, 72 percent of the works were by Indigenous female directors.

Three stand-out films chronicled the lives of prominent women leaders, Mankiller, about Cherokee Principal Chief Wilma Mankiller, 100 Years: One Woman’s Fight for Justice, about Eloise Pepion Cobell (Blackfoot), and Dolores, about Dolores Huerta, co-leader with Cesar Chavez of the first farm workers union. Among the long list of prominent and on-the-rise female directors were Alethea Arnaquq-Baril (Inuk), for Angry Inuk, Razelle Benally (Navajo/Oglala Lakota), for Raven & He Walks with Thunder and Kayla Briët (Prairie Band Potawatomi) for Smoke That Travels.

Ryle emphasizes the therapeutic effect of the films. “This work is still a real healing force for us,” he said. “To create this work is a healing mechanism for ourselves and certainly for individual artists but also for the community.”

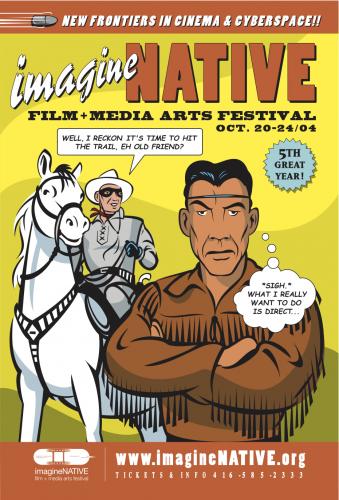

Ryle’s own showcase has been in the forefront of breaking the festival formula with innovative programming and international outreach. Launched in 2000, the festival grew out of the Aboriginal Film & Video Alliance, founded by Cynthia Lickers-Sage (Mohawk) and Vtape, a not-for-profit distributor of video art, along with other community partners. ImagineNATIVE is now the world’s largest presenter of Indigenous screen content.

Ryle says the festival started out as an artistic and cultural drive for Indigenous media in Canada. “imagineNATIVE was born out of a direct need because we didn't have a platform where the [Indigenous] artists can tell their stories and perspectives they wanted to.” He adds, “at the time all these others festivals were prescribing…what they believed was a genre, like Indigenous Cinema. Most of the films that were being presented at these places were created by non-Indigenous filmmakers.”

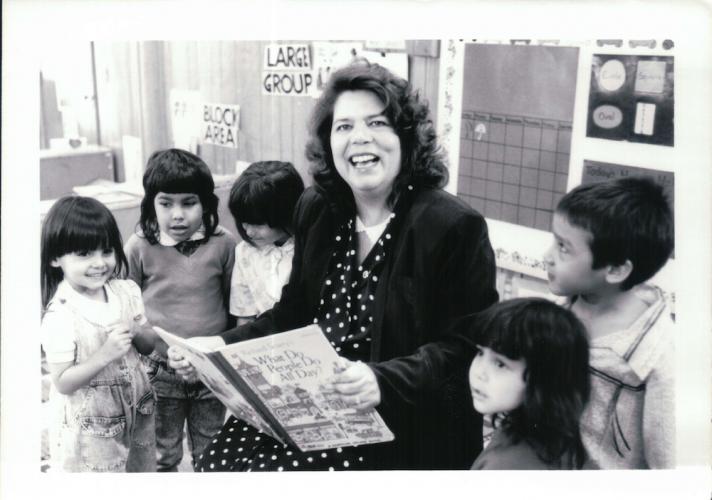

But Ryle was building on a quarter century of Native film festivals. The American Indian Film Institute (AIFI) was founded in 1975 by media analyst Michael Smith (Sioux) and actor Will Sampson (Creek). AIFI runs the oldest film festival in North America, the American Indian Film Festival in San Francisco, Calif. The Museum of the American Indian (MAI) followed in 1979 with the Native American Film + Video Festival, which continued under founder Elizabeth Weatherford when the MAI was taken over by the Smithsonian Institution as the National Museum of the American Indian in 1986. The Museum presented the Native American Film + Video Festival biennially in New York City until 2011. In 2000, it also founded the annual Native Cinema Showcase, which is still ongoing in New Mexico in conjunction with the Indian Art Market. Weatherford often observed that the festival was older than its Smithsonian affiliation.

In the late 1970s, Weatherford was the anthropology professor at the School of Visual Arts, and the idea for a festival grew out of screenings of ethnographic films. In 1978, she said, the MAI was lobbying for a relocation from its out-of-the-way 155th Street building to the U.S. Customs House in lower Manhattan, current location of the NMAI George Gustav Heye Center. The MAI proposed a film program downtown as the first step. Weatherford expanded the proposal to a fullscale festival, showing both 16-mm films and the then-new medium of video and using the richly appointed Collector’s Office of the Customs House as a theater. “We were the first festival that was international and indigenous,” she says.

The biggest increase in festivals took place in the 1990s and 2000s. The Sundance Institute added its Native American and Indigenous Program to the annual Sundance Festival in 1994. Each Native film festival has redefined Indigenous cinema storytelling with its own brand of approach; they range globally from Montreal First Peoples Festival in Quebec, to Skabmagovat Film Festival in Inari, Finland, to the L.A. Skins Festival in Los Angeles, Calif. An International Film + Video Festival of Indigenous Peoples rotates across Latin America under the auspices of CLACPI, the Coordinadora, Latinoamericano de Cine y Comunicacion de los Pueblos Indigenas (Latin American Council of Indigenous People’s Film and Communication).

As new festivals emerge each year, they create an ever-expanding community for Native and Indigenous filmmaking worldwide. To support that initiative many Native festivals have begun to tour their programming content to universities and tribal communities. ImagineNATIVE has its Film + Video Tour and American Indian Film Institute its Tribal Touring Program. The National Museum of the American Indian is in talks to tour Native Cinema Showcase to museums and eventually to tribal communities.

Establishing lasting relationships with other organizations can be key for any fledgling festival. When imagineNATIVE was in its beginning stages, it reached out to the NMAI and its Film and Video Center. The relationship has shared new thoughts and formed dialogues as either party invited panelists, guest programmers or co-presenter for films. Ryle called it a “natural bridge” between both institutions. “That was a natural fit really, where we at least got to the position where we were able to build those partnerships a little more concretely.”

imagineNATIVE has continued creating partnerships with other festivals and artists, creating a global network for Indigenous cinema. Canada has set up an Indigenous Screen Office to support the development, production and marketing of indigenous content.

In his 16 years at the festival, Ryle has seen a parallel between the growth of Indigenous cinema and Native film festivals. “The more indigenous film festivals there are, the stronger our industry is. I really believe that. And that was the case for the early years. Especially at a time when the level of production wasn’t as high as it is now.

“Probably the biggest impact I think that our festivals have,” he says, “is that it really presented that perspective and did the work of bridge building, community building, educating, entertaining and enlightening, that really wasn’t happening elsewhere.”

The growth of an Indigenous cinema has given Native film festivals a scope of programming content that has diversified each year. Topics range from environmentalism and activism to politics and cultural preservation. Audiences have begun to take notice. Where once Native cinema was a niche genre in larger festivals, it is now in the forefront of international cinema. The heightened interest has brought significantly higher audiences to many Native festivals. NMAI’s Native Cinema Showcase this year, its 17th annual, drew the largest numbers ever, with more than 2,700 people. In its six days, it featured 50-plus films from seven countries.

So how do Native film festivals like imagineNATIVE maintain their success within an industry that is continuously growing? imagineNATIVE created its own structure, a sort of DNA that helps continue the success of the festival. “Success as an organization is our adherence to the original mandate that Cynthia and others helped instill within the structure of imagineNATIVE,” says Ryle. “An imagineNATIVE DNA, is to be an Indigenous artist focused festival, to present the works of Indigenous artists and their screen culture, their visions and creativity on the screen, rather than one that’s programmed solely on content.”

As for the future of Native and Indigenous cinema, Ryle says, “Over the past 10 years these artists are creating such a huge body of work that you and I never had growing up. If you look at our nieces and nephews, what this is going to leave them is incredibly profound, not just them too, but non-native kids as well. I mean this is something that just never existed before. And I'm really excited how that will inspire generations of filmmakers and storytellers, but how that will really impact the fabric of our society.”