Imagine that it’s 9,000 years ago. The ice sheets have retreated, and it’s time to move your family northward to better hunting grounds as the climate warms. You are a member of a nomadic tribe. Whether you are in what would become Europe, the Mideast, Siberia, China or North America doesn’t matter. What you take with you is not so important. You are indigenous and resourceful. You can make whatever it is you need when you get to where you are going. But one portable thing that is definitely going with you is your song – perhaps many different songs that you learned from your ancestors.

Maybe you will take that one drum that sounds so good, or your stringed instrument or the rattle your grandfather gave you. When you finally arrive at the promised land you seek, there will be a celebration, a thanksgiving, and there will be singing and storytelling. The beat of the drum, the vibration of strings and the sound of percussion will match the tempo of your heartbeat, and you will be one with creation. All will be well.

As a professional musician making my living in the performing arts, I think about these things and about how far we have all come. In the 1950s when I was born, the “Beat Generation” began to break away from swing jazz and other “conventional” art forms to seek more tribal ways of approaching music and storytelling. The poets inside the coffee houses of Paris, Greenwich Village and North Beach, San Francisco only needed a set of bongos and a pen to get their point across. Then the radio stations in the south began to broadcast African-American influenced “race music,” and the white suburbs first heard the beat of the drum and the twang of the “tar” in a whole new way.

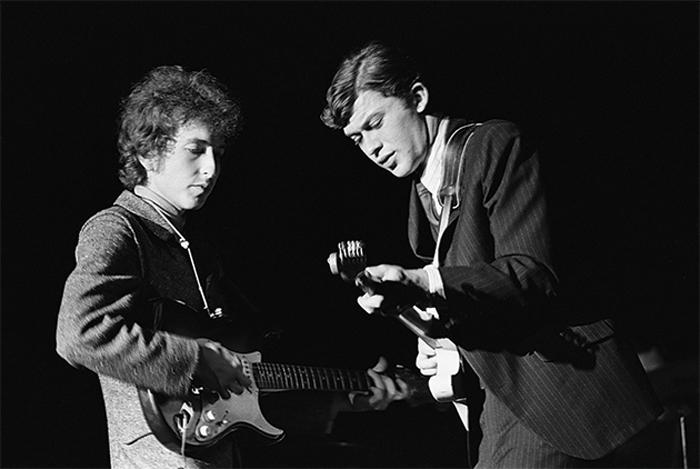

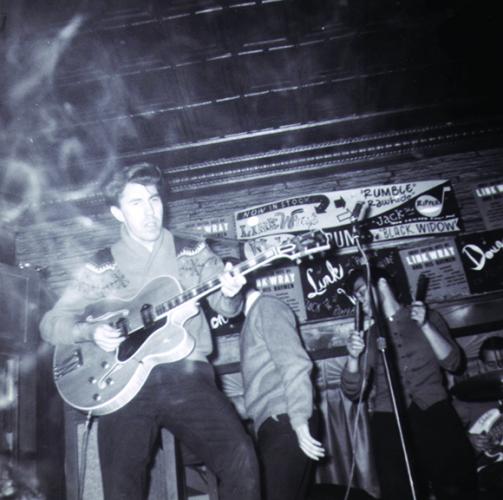

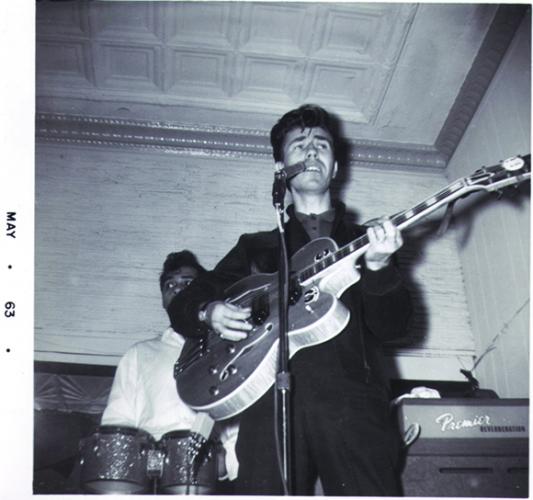

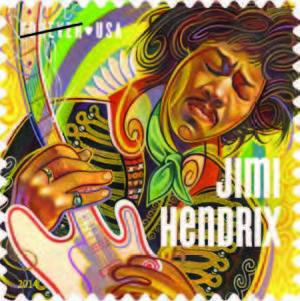

Native artists such as Link Wray took that tribal drumbeat and augmented it with his primitive electric guitar style, adding his name to the foundations of the “Rock Pile.” Later, Jimi Hendrix, who had Cherokee blood, wrote and recorded songs during his amazing and all too brief career that transformed rock music. Mark Lindsay, of Paul Revere and the Raiders fame, signed me to my first record deal. He told me how he had become a record company executive only after the success he had with his song “Indian Nation,” which honored his Native bloodline with a realistic story of the plight the Cherokee peoples had endured. And who can forget the amazing guitar solo on Jackson Browne’s “Doctor My Eyes” by Cherokee Jessie Ed Davis, alongside whom I had the pleasure of working on a Taj Mahal record years ago? Founding member of The Band and fellow Mohawk bloodline brother Robbie Robertson has become not only a well-known rock guitarist, but also a fine composer of movie soundtracks and record producer. Native musicians are interwoven directly into the heart of rock ‘n’ roll.

While all these changes were going on in pop culture, the indigenous peoples of North America were doing the same thing they had been doing for thousands of years. Bending and carving wood into deep hoops and stretching animal hides over the edges. Filling gourds and horns with seeds. Singing melodies with catchy, repetitive phrases that everyone could learn and pass down from generation to generation. Telling the stories of life’s trials, romance, beauty, hunting successes and so on. By the 1960s, this nation had finally caught up to the ways the indigenous American had expressed him- or herself all along. The powerful driving beat of the drum and the song in their heart was not only for celebrations and special events, but sustained daily cultural lifestyles that continue right up to modern times.

The Baby Boomer generation of today is immersed inside this musical and cultural revolution and won’t let go. Everywhere you look someone is bopping along under their earbuds, a slave to their iPod. Popular music drives the very heart of advertising and commerce, and is the soundtrack and tapestry of our memories and day-to-day lives. Rock ‘n’ roll has endured longer than any other contemporary musical art form. Swing music (1935–1950) only lasted 15 years. Disco (1975–1980) only five. But rock ‘n’ roll (1955–present) is now 60 years old and still going strong. Why is this? The drumbeat, the storytelling, the vibration of strings and the catchy melodies have been around since the Ice Age. It’s inescapable. It’s become a part of our DNA. North America is where rock’s fusion took place – and with good reason.

Kenny Lee Lewis has been a writer, producer, guitarist, bassist and vocalist for The Steve Miller band for more than 34 years. He has a drop of Mohawk and Cherokee blood, and is not afraid to use it.