Surmounting the color bar, racial heckling and obnoxious nicknames, some 50 enrolled members of American Indian tribes have played professional baseball since the start of the major leagues.

Although Indians didn’t face the official segregation that shunted great black players into the Negro Leagues, the integration of indigenous people was a painstaking process marked by race-baiting and hazing, similar to the ordeal faced by Jackie Robinson and the first African Americans to enter the major leagues after 1947.

Indian players did have the benefit of a feeder system from the powerful athletic program at Carlisle Indian Industrial School. (Early players also came from the Haskell and Chilocco Indian Schools and the lapsed Indian institution, Dartmouth College.) In fact, the number of Indians in the Major Leagues dried up after the demise of Carlisle in 1918, reviving only in present times. But their main advantage was their great natural ability.

In the early 1900s New York Giants catcher John Tortes Meyers (Cahuilla) wrote in a newspaper column about his teammate the great Jim Thorpe (Sac and Fox), “It would be false modesty on my part to declare that I am not thoroughly delighted with the fact that my race has proven itself competent to master the white man’s principal sport.”

There was no watershed moment, but fifty years before Robinson officially became major league baseball’s first African American player, Louis Sockalexis (Penobscot) arrived on the scene as the big league’s first high-profile American Indian.

Born on the Penobscot Indian reservation near Old Town, Maine, on October 24, 1871, Sockalexis was the son of an influential elder of the Bear clan. He was educated and played baseball at the Jesuit’s St. Ann’s Convent School. He later excelled in baseball, football and track at the College of the Holy Cross and then transferred to Notre Dame.

Sockalexis made his big league debut with the Cleveland Spiders on April 22, 1897. Defenders of the use of Indian mascots or titles often argue that the name of the Cleveland Indians originated as a tribute to Sockalexis. But the attitude of his day was hardly respectful. The sportswriter Elmer E. Bates described it in an 1897 column in the Sporting Life newspaper:

War whoops, yells of derision, a chorus of meaningless “familiarities” greet Sockalexis on every diamond on which he appears. In many cases these demonstrations border on extreme rudeness. In almost every instance they are calculated to disconcert the player…All eyes are on the Indian in every game. He is expected not only to play right field like a veteran, but to do a little more batting than anyone else. Columns of silly poetry are written about him, hideous looking cartoons adorn the sporting pages of nearly every paper. He is hooted at and howled at by the thimble-brained brigade on the bleachers. Despite all this handicap, the red man has played good steady ball.

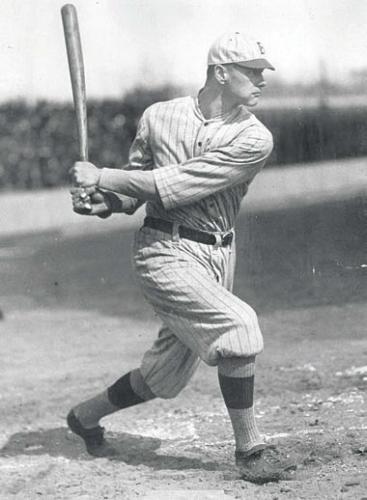

Sockalexis was the first of many Indian players to be called “chief” inappropriately. But perhaps the best known was pitcher Charles Albert Bender (Ojibwe). Bender was born on May 5, 1884, in Crow Wing County, Minn., and is one of seven major leaguers to emerge from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa. Bender spent 13 of his 16 big-league seasons with the Philadelphia Athletics, and his 212 wins rank him third in franchise history.

One of two American Indians in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Bender would have preferred to be called Charlie or even Albert, which is how his manager Connie Mack referred to him, but the nickname “Chief” stuck and he took it all the way to his grave.

Like Sockalexis, Bender was also on the receiving end of racially motivated taunting, rattling him enough to yell back at hecklers: “You ignorant, ill-bred foreigners. If you don’t like the way I’m doing things out there, why don’t you just pack up and go back to your own countries.”

Bender also felt that being a major league baseball player afforded him more opportunity than he might have found in any other profession.

“The reason I went into baseball as a profession was that when I left school, baseball offered me the best opportunity for both money and achievement. I adopted it because I played baseball better than I could do anything else, because the life and the game appealed to me and because there was so little of racial prejudice in the game. There has scarcely been a trace of sentiment against me on account of my birth. I have been treated the same as other men,” he said to the Chicago Daily News in October 1910.

Bender and the New York Giants catcher John Tortes Meyers (Cahuilla) are jointly responsible for an indigenous milestone. They played opposite each other in the 1911 World Series, just the eighth fall classic to be played between the American and National leagues and the first to feature American Indians on each team. Bender won two of his three starts in the Series, including the clincher in game six, while extending his streak of seven consecutive complete games in World Series play (he would set a still-standing record of nine straight).

Opposing Bender’s Athletics was New York Giants catcher Meyers. Born in Riverside, Calif., on July 29, 1880, Meyers attended Dartmouth College in New Hampshire (an Ivy League school originally intended to educate Indians.) He played his way through semi-pro teams in Arizona and New Mexico and the minor leagues before making his major league debut in 1909. During the month-long spring training season, he hit an astonishing 29 home runs. Meyers batted .332 in 1911, .358 in 1912 and .312 in 1913, and the Giants reached the World Series in all three seasons. Manager John McGraw called him, “the greatest natural hitter in the game.”

Outspoken on Indian affairs during and after his playing days, Meyers chronicled his own career as a columnist for the New York American newspaper from 1912 to 1914. Two years after his death in 1971, Meyers was inducted into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame at Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kan.

Bender’s alma mater, Carlisle Indian School, is much maligned these days for its original policy of suppressing tribal identity, but by the turn of the 20th century it had become a major force in American athletics. Baseball entered its curriculum in 1886. It also fielded championship football teams and sent contenders to two Olympics. Seven alumni advanced to Major League baseball.

The most famous, of course, was the great all-around athlete Jim Thorpe, whose Olympic achievements are detailed elsewhere in this issue. After being driven out of amateur athletics, Thorpe signed with the New York Giants as an outfielder. As a baseball player, Thorpe did not live up to the lofty expectations of Giants manager John McGraw, who complained that Thorpe couldn’t hit curve balls. The two also clashed personally. Thorpe struggled through three seasons in New York. He fared much better in the minors, compiling a .320 batting average during seven seasons. In his final major league season with the Giants and Boston Braves in 1919, he hit .327.

Other Carlisle baseballers made their mark in the majors and minors. Bender’s teammate at Carlisle, Louis Leroy (Seneca), born in Omro, Wisc., on February 8, 1879, enrolled at the Haskell Institute in Kansas when he was 16 and transferred to Carlisle three years later. Leroy pitched only briefly in the major leagues (New York Yankees, 1905–06, Boston Red Sox, 1910) but enjoyed a distinguished 18-year career in the minor leagues.

Other Carlisle major leaguers include Frank Jude (Cincinnati, National League, 1906), Mike Balenti (Cincinnati, 1911, St. Louis, American League, 1913), Charles Roy (Philadelphia, American League, 1906) and George Johnson (Cincinnati, National League, Kansas City, Federal League, 1913–15).

Not all the great names came from Carlisle. Zachariah Davis Wheat was born in Hamilton, Mo., on May 23, 1888, to a Cherokee mother and a father descended from Puritans who founded Concord, Mass., in 1635. Wheat made his big league debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1909. Even though he retired from the major leagues in 1927, he still holds Dodgers team records for hits (2,804), singles (2,038), doubles (464), triples (171), total bases (4,003), at-bats (8,859) and games played (2,322). Wheat hit higher than .300 in 14 of his 19 major league seasons, and finished his 19-year career with a .317 career mark. In 1959, he became the second American Indian elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

George Howard Johnson (Ho-Chunk) from Winnebago, Neb., achieved a bit of baseball fame on April 23, 1914, as the pitcher who gave up the first home run at Chicago’s Wrigley Field when he played for the Kansas City Packers of the Federal League. Johnson racked up 125 wins during eight minor league seasons with a 2.02 ERA. He threw a no-hitter in his final professional season in the Pacific Coast League in 1917.

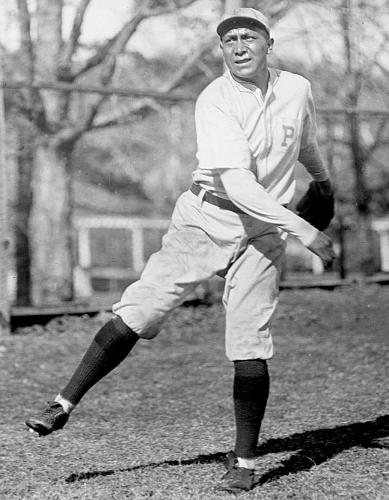

Although Moses J. Yellow Horse (Pawnee) pitched only two seasons for the Pittsburgh Pirates, from 1921 to 1922, he retained a cult-like status among fans in Pittsburgh for decades to follow. From Pawnee, Okla., Yellow Horse was educated at the Pawnee Agency School and the Chilocco Indian School. Possessing a blazing fastball, he made his big league debut on April 15, 1921. Excited by their newfound star, Pirates fans whooped and hollered at the prospect of Yellow Horse appearing in games. The chant “Bring in Yellow Horse” would resonate in the Pirates bleachers for decades after his brief career was over. Yellow Horse was inducted into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame in 1971 and the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame in 1994.

Most commonly referred to as “Pepper” Martin, St. Louis Cardinals outfielder John Leonard Roosevelt Martin (Osage) from Temple, Okla., was also known as the Wild Horse of the Osage, for his aggressive base running and all-out style of play. He was inducted into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame in 1992.

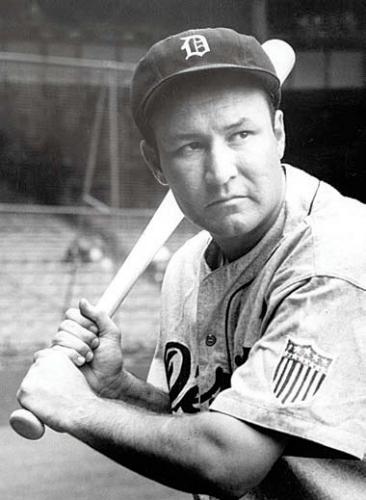

Slugging first baseman Rudy York made his major league debut with the Detroit Tigers in 1934 and hit 277 home runs with 1,152 RBI in his 13-year big league career. Born in Ragland, Ala., York’s fractional Cherokee ancestry and inconsistent fielding contributed to making him an object of derision to sports writers, who called him “part Indian and part first baseman.” However, his skill with the bat earned him seven All Star game appearances and garnered MVP votes in nine seasons. York led the American League with 34 home runs and 118 RBI in 1943.

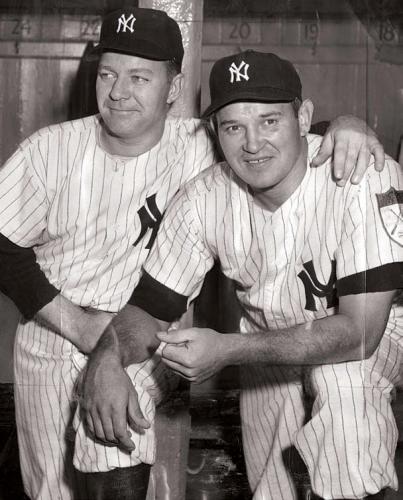

New York Yankees’ hurler Allie Reynolds (Creek) ranks among the most successful pitchers in World Series history. His seven Series victories are second only to Whitey Ford’s 10. He was born in 1917 on the Muscogee reservation in Bethany, Okla., to a mother who was a member of the Muscogee (Creek) tribe. During his time with the Yankees he was known alternately as “Chief” and “Superchief,” a double entendre reference to his Indian origin and a railroad train of the time.

Former teammate Bobby Brown, said it was meant as a flattering term.

“Some of you are too young to remember, the Santa Fe Railroad at that time had a crack train [Superchief] that ran from California to Chicago, and it was known for its elegance, its power and its speed. We always felt the name applied to Allie for the same reasons,” said Brown. He added that Reynolds did not necessarily appreciate the nickname. Reynolds is honored with a bronze bust at the Bricktown Ballpark, home of the AAA Oklahoma City Redhawks.

The Indian tradition in baseball is currently having a revival. Three Natives are now playing in the major leagues. When St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Kyle Lohse (Nomlaki Wintun), from Chico, Calif., took the mound in game three of the 2011 World Series, it was the first time a Native pitcher started a Series game since Yankees hurler Reynolds won game six in the 1953 Series.

Prior to Lohse, Yankees relief pitcher Joba Chamberlin (Winnebago) from Lincoln, Neb., was the last Native pitcher to appear in the World Series, making three relief appearances against the Philadelphia Phillies in the 2009 Fall Classic.

Third on the list, Boston Red Sox outfielder Jacoby Ellsbury (Navajo) from Madras, Ore., finished second in American League MVP voting last season.

Chamberlin says his Native heritage “was always a part of my life and it’s always been significant, and as I’ve gotten older, it’s become more significant. As I got older, I appreciated it more. I think we all play a part from the beginning to the players playing now.

“Opportunities on the reservation are few and far between, so… it’s good to see that there are some current players right now that can give hope and faith to those kids on the reservation.”