Many cultures honor their warriors, but some give even greater praise to the warriors who help make peace, or even better, avert war. Some of the greatest American Indians rank in the second group. The role of diplomat, negotiator and promoter of peace has always commanded the highest esteem among Native peoples.

As we honor veterans who have served in the U.S. Armed Forces, we must also honor the American Indians who have promoted peace and protected their people in other capacities. Some were leaders, taking their people away from danger. Many were diplomats, seeking to resolve conflict through negotiations. In our own day, activists and litigants have fought a different fight, using protests and courts to change the laws of the land.

Tribal diplomacy operated by formal protocols long before arrival of the Europeans. Official delegations carried wampum belts as credentials. Exchange of gifts continued in dealings with colonial powers. Each meeting produced a round of official presents, notably numerous Indian peace medals that European monarchs and then the U.S. government gave to chiefs and members of Native delegations.

From the time of George Washington in the late 1700s, tribal delegations journeyed to the nation’s capital in often unsuccessful efforts to end hostilities on the frontier. During the 19th century, tribal delegations were wined, dined and often cheated, leaving a trail of disadvantageous dealings. But, as Herman Viola observed in “Diplomats in Buckskins,” many famous tribal leaders made the trip more than once, gaining in skill and sophistication with each visit. Over time, the diplomacy built up a record of government-to-government relations that is now the bedrock of Indian law.

Following are some outstanding Indigenous leaders who sought to make and keep peace.

A Delaware Visionary

White Eyes, a Unami-speaking Delaware (Lenape), was a chief in the Ohio Country during the American Revolution. In the early 1770s, violence on the frontier between whites and American Indians threatened to lead to open warfare. White Eyes unsuccessfully attempted to prevent what would become Lord Dunmore’s War in 1774, fought primarily between the Shawnee and Virginia settlers. However, he served as an emissary between the two sides and helped negotiate a treaty to end the war.

Although most Delaware people opted for neutrality in the Revolutionary War, Chief White Eyes favored the American colonials. In April 1776, the chief addressed the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In order to end the violence on the frontier and bring peace between Native peoples and the “Long Knives,” he pushed for the creation of a separate Indian state, one set apart for the benefit and protection of Indian nations.

In 1778 at Fort Pitt, he completed an alliance with the United States, the first federal–Indian treaty in the new nation’s history. The sixth article of the treaty gave the Delaware people the right “to join the present American confederation [Articles of Confederation] and to form a state [the 14th state] whereof the Delaware Nation shall be the head and have a representation in Congress.” The treaty also provided for White Eyes to serve as guide for the American confederates when they moved through the Ohio Country to strike at their British and Indian enemies near Detroit.

In early November 1778, White Eyes and his warriors joined a U.S. expedition as a guide and negotiator. Soon after, the Americans reported that White Eyes had died. The cause of his death remains open to question. Yet, Herbert Kraft, a distinguished anthropologist and authority on the Delaware people, insists that while White Eyes was reported to have died of small pox, he was actually assassinated by white settlers in the Ohio Country. After the chief ’s death, the alliance with the United States eventually collapsed along with the idea of a Delaware people–lead state. Thus, despite White Eye’s efforts to protect his people, the Delaware Treaty of 1778 also marks the first in a long history of broken accords between American Indians and the federal government.

Haudenosaunee Diplomats

The Iroquois, or Haudenosaunee Confederacy of the Six Nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora), was deeply riven by the Revolutionary War, pitting some of these nations against others. The Oneida and Mohawk even fought each other in a pitched battle. In a heroic attempt to end the bloodshed, two Mohawk and two Oneida leaders traveled to the British-held bastion of Fort Niagara in 1779. These aged chiefs, one well into his 70s, carried a letter from American General Philip Schuyler requesting a truce to initiate a prisoner exchange. The letter guaranteed safe passage for the British to attend a future meeting in rebel-held Albany. However, the four Iroquois emissaries had a different objective: to restore peace in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. All four—Oneida chiefs Good Peter and Skenandoah who were allied to the Patriot cause and Mohawk chiefs Little Abraham and Johannes Crine who espoused neutrality—were arrested and incarcerated in the dismal military jail at the fort. Little Abraham, the apparent leader of the delegation, perished as a prisoner of war in Fort Niagara’s black hole, a 4-by-4-foot underground, windowless cell.

The four Haudenosaunee were not the first or last to act as spokesmen for peace. Indeed, this role is set forth in “Gayanashagowa,” the Great Binding Law of the confederacy. In traditional beliefs Deganiwidah, the prophet known as Peacemaker, came from his home in Huronia to stem the internecine bloodshed among Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca villages. Through the Peacemaker’s efforts and the great oratory of his disciple Hiawatha, they were able to establish the Haudenosaunee Confederacy on the principle of peace.

Indeed, the Haudenosaunee—who span both sides of the United States–Canada boundary—have frequently brought their complaints before international forums such as the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland. In the 1920s, Chief Levi General, known as Deskaheh, was from the Grand River Territory in Canada and attempted to bring action against the Canadian government. Among other issues, Deskaheh insisted that the Canadian government had interfered in Haudenosaunee traditional affairs, specifically in its efforts to impose an elected council on the people of the Six Nations Reserve (which was ultimately done in 1924). Canada, complained Deskaheh, had also violated Indian border-crossing rights guaranteed in the Jay Treaty of 1794. From Deskaheh’s death in 1925 onward, the Haudenosaunee have continued to bring their concerns before international organizations such as the United Nations.

At times, the Haudenosaunee were joined by the Hopi of the Southwest, whose pacifism is rooted in their religious beliefs. The Hopi have long maintained that humanity now lives in the “Fourth World,” its last chance to get things right and save the planet. These efforts and the work of other Indigenous peoples around the world culminated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People adopted by the General Assembly in 2007.

Fighting Through Law

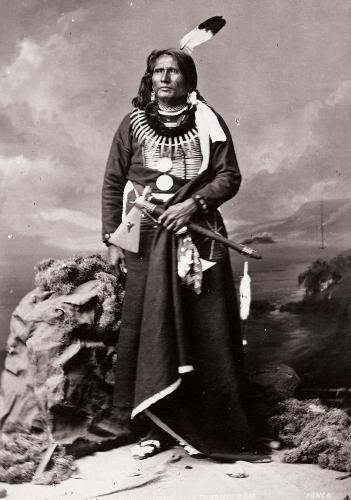

Standing Bear, a Ponca chief also known as Ma-chú-nu-zhe, chose another path to defend his people—U.S. law. In the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, the U.S. government illegally gave Ponca lands in Nebraska to the Santee Dakota as part of its negotiations to end Red Cloud’s War. The Ponca were removed to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. Many lost their lives to starvation, malaria and overall governmental mismanagement. One of these victims was Bear Shield, Standing Bear’s eldest son. Standing Bear had promised his son to bury him in the Ponca homeland along the Niobrara River valley. In January 1879, Standing Bear left Indian Territory for Nebraska with his son’s remains. Under orders from the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Brigadier General George Crook arrested the chief for having left the reservation without permission.

At the trial of United States ex rel. Standing Bear v. Crook in Federal District Court in Omaha, Standing Bear spoke on his own behalf. Raising his right hand, he said, “That hand is not the color of yours, but if I prick it, the blood will flow, and I shall feel pain. The blood is of the same color as yours. God made me, and I am a Man.” On May 12, Federal Judge Elmer Dundy ruled that “an Indian is a person” within the meaning of “habeas corpus,” a writ that brings a person before a court. The decision was a landmark, recognizing that an American Indian is a “person” under the law and entitled to its rights and protection.

Standing Bear returned to the land by the Niobrara River and buried his son alongside his ancestors. When the chief died there in 1908, he was buried alongside him. In 2019, in a formal ceremony in the U.S. Congress, a statue of this remarkable Ponca replaced one of William Jennings Bryan in Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol, in accordance with a resolution passed by the Nebraska State Legislature.

Defending Fishing Rights

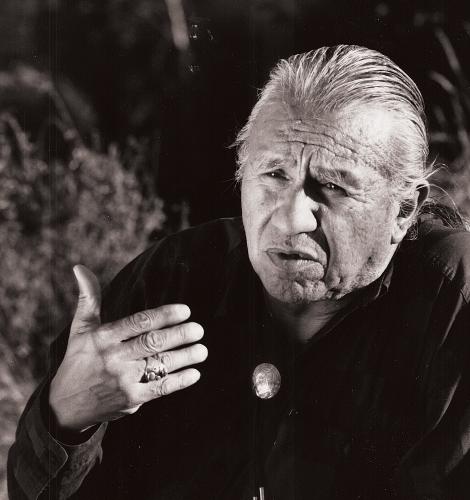

During the social protests of the 1960s, Billy Frank Jr., a Nisqually, led Northwest Indians in the fight for the recognition of their fishing rights. Hydroelectric power development and increasing commercial fishing had taken its toll on Northwest salmon populations. In 1965, as the region’s salmon continued to decline, the tension between Native and non-Native sportsmen and commercial fishermen turned violent. Frank, who had been arrested in protests more than 50 times since 1945, maintained that the Nisqually and other Native Nations in the state of Washington had been guaranteed their rights to fish by treaty. His actions attracted national attention and support from noted Hollywood actors.

Ultimately, like Standing Bear, Frank chose a legal path to achieve his objective. In 1974, Federal Judge George Boldt made a historic decision in U.S. v. Washington that held that the 20 tribes of western Washington had rights to half of the harvestable salmon and were co-managers of the salmon resources in the state. This decision transformed Frank into a leading advocate of regional cooperation and a highly respected mediator. He became chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission in 1981.

By the time of his death in 2014, his career as an activist culminated in a major movement mobilizing both Natives and non-Natives in the Northwest to preserve and protect the environment. His long-time friend Hank Adams (Sioux-Assiniboine), a noted behind-the-scenes peacemaker in his own right, says, “Billy readily gained everyone’s trust, relying on a mutuality of respect.” Adams places Frank’s legacy in the long tradition of Native diplomacy. “Indian treaty-makers of nearly 200 years ago gave voice to the voice of Billy Frank Jr. and he to theirs for a lifetime.”

In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded Frank the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously. Soon after, the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge was named in Frank’s honor.

They Also Served

American Indian service to the United States and Canada went well beyond serving as warriors on far-off battlefields. Some Native leaders chose a different path, to fight for their own people’s rights. White Eyes served as a go-between to promote peace and the dream of an Indian state. Iroquois diplomats such as Little Abraham, Johannes Crine, Scanando and Good Peter hoped to end the violence of the Revolution. Deskaheh tried to get international recognition for Haudenosaunee in their grievances against Canada. Standing Bear and Billy Frank Jr. both changed American law on behalf of Native people. All exemplify the other great Native traditions of diplomacy and peacemaking.