“We serve this country because it’s our land. We have a sacred purpose to protect this place.”

- Jeffrey Begay, Diné [Navajo] veteran

American Indians have served in our nation’s military since colonial times. In recent decades, they have served at a higher rate in proportion to their population than any other ethnic group. Why? For many, military service is an extension of their warrior traditions. Others serve to reaffirm treaty alliances with the United States. Still others serve for sheer love of home and country.

Throughout Indian Country, servicemen and women are some of the most honored members of their communities. Yet they remain unrecognized by any landmark in our nation’s capital. That will soon change.

The United States Congress has charged the National Museum of the American Indian with creating a memorial on its grounds to give all Americans the opportunity “to learn of the proud and courageous tradition of service of Native Americans.” Their legacy deserves our recognition.

Why Do American Indians Serve?

It doesn’t seem to make sense: why would American Indians serve a government that overran their homelands, suppressed their cultures and confined them to reservations? The reasons are complex.

For thousands of years, American Indians have protected their communities and lands. A warrior’s traditional role, however, involved more than fighting enemies. Warriors cared for people and helped in any time of difficulty. They would do anything to help their people survive, including laying down their lives. Many American Indians view service in the U.S. armed forces as a continuation of the warrior’s role in Native cultures.

World War I

When the United States entered “the war to end all wars” in April 1917, Native Americans signed up to fight in and support it. Some 3,000 to 6,000 Native men enlisted and another 6,500 were drafted. About two-thirds served in the infantry, winning widespread praise for bravery and achievement. But the cost was high: about five percent of Native combat soldiers were killed, compared to one percent of American forces overall.

American Indians supported the war in other ways. At home, some 10,000 Indian women joined the Red Cross, donating time, money and clothing. Native people also bought war bonds. By the war’s end in November 1918, American Indians owned $25 million in bonds, about 75 dollars for every Native man, woman and child.

After fighting for democracy in Europe, many Native veterans expected that the United States would reward their patriotism by granting all of their people citizenship and recognizing the right of tribal self-determination.

Code Talkers

During World War I and World War II, a variety of American Indian languages were used to send secret military messages – codes that enemies were never able to break.

In World War I, Choctaw and other American Indians transmitted coded messages by telephone in their tribal languages. Although not used extensively, the telephone squads were key in helping the United States win several battles that ended the war.

Beginning in 1940, the army used American Indian recruiters to find Native-language speakers who were willing to enlist. The Marine Corps recruited Diné [Navajo] code talkers in 1942 and very soon established a code-talking school.

World War II

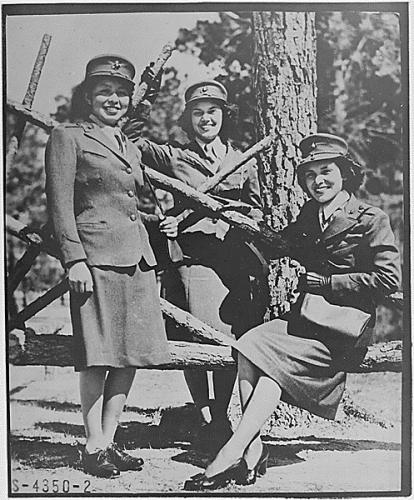

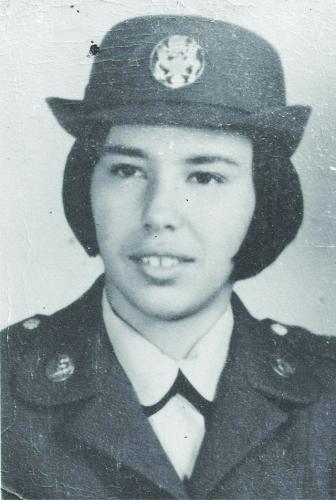

American Indians enlisted in overwhelming numbers after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Forty-four thousand of a total Native American population of 350,000 saw active duty, including nearly 800 women. For this service they earned at least 71 Air Medals, 34 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 51 Silver Stars, 47 Bronze Stars and five Medals of Honor.

“People ask me, ‘Why did you go? Look at all the mistreatment that has been done to your people.’ Somebody’s got to go, somebody’s got to defend this country. Somebody’s got to defend the freedom. This is the reason why I went.”

— Chester Nez (Diné [Navajo]), World War II and Korean War veteran

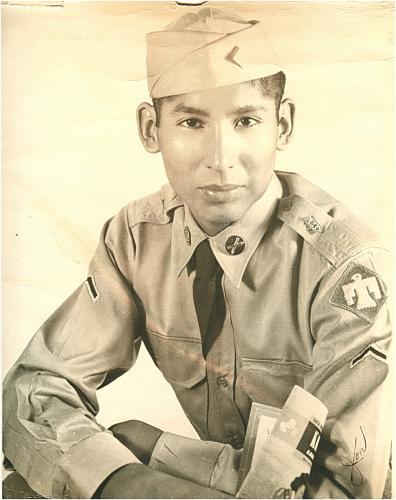

Korea

The Korean War began in June 1950, when Communist North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel dividing the Korean Peninsula. For the next three years, American forces – including approximately 10,000 American Indian soldiers – along with troops from 15 other nations, fought to prevent a Communist takeover. Considered a “police action” because Congress issued no formal declaration of war, the Korean War was nevertheless bloody and brutal. Some 33,739 American soldiers died in battle, including 194 Native Americans.

Vietnam

Of the 42,000 American Indians who served in the U.S. armed forces during the Vietnam conflict (1964–75), 90 percent were volunteers. Approximately one of every four eligible Native people served, compared with one of 12 in the general population. Of those, 226 died in action and five received the Medal of Honor.

Like many other Vietnam veterans, American Indians were often deeply traumatized by what they experienced. Some noticed similarities between the Native and Vietnamese colonial experiences. As one veteran observed, “We went into their country and killed them and took land that wasn’t ours. Just like the whites did to us. We shouldn’t have done that. Browns against browns. That screwed me up, you know.”

When the veterans returned, many found solace and healing in their communities’ ceremonies and honors. Many also joined political organizations, such as the American Indian Movement and the National Indian Youth Council, to work for social justice and change.

Global Conflicts in the 21st Century

Since the Gulf War (1990–91), the United States has been engaged in an ongoing series of conflicts, primarily in Afghanistan and Iraq. American Indian men and women continue to serve in high numbers at home and abroad. According to the Department of Defense, more than 24,000 of the 1.2-million current active-duty servicemen and women are American Indians.

Be Part of a Historic Moment: The National Native American Veterans Memorial

“This is a tremendously important effort to recognize Native Americans’ service to this nation. 3We have so much to celebrate.”

– The Honorable Ben Nighthorse Campbell (Northern Cheyenne)

Native Americans have participated in every major U.S. military encounter from the Revolutionary War to today’s conflicts in the Middle East, yet no landmark in our nation’s capital recognizes this contribution.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian will create that landmark: the National Native American Veterans Memorial. The anticipated dedication of this tribute to Native heroes will be on Veterans Day 2020.

The National Museum of the American Indian is depending on your support to honor and recognize these Native American veterans for future generations.

![Diné [Navajo] code talkers kneeling in leaves](/sites/default/files/styles/media_style_for_slider/public/2017-12/banner_7.2.jpg?itok=mvhrDMsJ)