Rick E. Bartow, the Mad River Band Wiyot artist and sculptor, never saw combat when he served in Vietnam, but his experiences were still harrowing. Drafted after college and assigned to a signal unit, he spent his afterhours as a rock musician. His group played at firebases, for frontline units with morale problems and at hospitals for the severely wounded.

The U.S. Army awarded Bartow a Bronze Star for his musical service to injured soldiers, but it couldn’t help his own wounds. When the medal arrived back home in Oregon, he threw it out. (His mother retrieved it.) Badly in need of healing, he turned to art. For the next four decades, themes of recuperation and survival kept recurring in his prolific outpouring of drawings and in his monumental carvings.

Bartow’s most recent work, two large carved poles entitled We Were Always Here, will be raised at the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall this September 21, the eighth anniversary of the Museum’s opening. The dedication will be the first time they will be upright.

The two red cedar poles are topped with animal figures, and they add layers of meaning to the work’s title. Bartow says at one level his work refers to the animals, such as the ones in the carvings, who still live in the region and in the museum’s native habitat. In another, it is a testament to indigenous people, past, present and future, who have remained strong despite insurmountable challenges. Thirdly, it is an offering of respect to the spirits who reside within the baskets, textiles and other artifacts in the Museum collection.

This will not be the first time Bartow has brought his healing art to Washington, D.C.

In 1997, he was one of 12 Native artists included in the exhibition Twentieth Century American Sculpture at the White House: Honoring Native America, displayed in the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden. Bartow contributed Cedar Mill Pole, a 26-foot-tall pole incised with a ribbon-like pattern and a human head peering from the top. As the artist explained, it told “a story [about] the tree, of grief, of people who lost their land. Yet it also speaks of embracing the future.” He carved it to heal an Oregonian community divided over a road expansion project that razed a grove of cedar trees. The pole came from one of the removed trees and now stands in that town’s new green space.

Another sculpture, From the Mad River to the Little Salmon River, or the Responsibility of Raising a Child (2004), is in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian. It features a coyote with a basket carrying a child on its back. Animals like an eagle, salmon and raven surround and guard the child. The work is a personal story about “pride of place, love, lost and found, [and] survival,” Bartow says. The trickster Coyote can create chaos and harm. Consequently, parents may need help, especially from the love and support of community members, in raising a child.

Bartow was born in 1946 in Newport, Ore., a seacoast town more than 100 miles southwest of Portland. Even as a child he was an incessant doodler, and his sister encouraged him to earn a bachelor’s degree in art education from Western Oregon State University in 1969. When the draft and Vietnam disrupted his life, he returned home to a hard fight with drink and post-war stress. Support from friends and family, and his omnivorous interest in art, helped him recover, but a viewer who is so inclined can see signs of the struggle in many of his large output of pastels, drawings and prints.

Charles Froelick, who represents Bartow through the Froelick Gallery, notes the wide range of influences on his work, but adds, “The content is very often guided by his personal experiences.”

Bartow draws heavily on the teeming wildlife of his Pacific Coast home. A keen observer of the ravens, coyotes, eagles and ospreys around his home and studio, he takes great interest in the animals’ movements and respects them as teachers of life and behavior. His drawings sometimes incorporate a human face in the animal’s head or body.

The animal mentors the Bear and the Raven have a strong presence in We Were Always Here, commissioned for the Museum, as does his human community. The Raven sits atop one of the two 20-foot poles carved from western red cedar, and the Bear sits on the other. Says Bartow, “the Bear and Raven, Healer and Rascal, sit atop the sculpture poles: one, slow and methodical, fiercely protective of her children, the other a playful, foible-filled teacher of great power.” The Bear also represents Walter Lawrence Klamath, a Siletz elder who passed away in 2010 and will watch and protect from high above.

Since October 2011, Bartow and others have been working on the poles in a Newport studio where they can be carved flat. The poles have been “a product of the spirit,” Bartow says. Many people have assisted. Bartow asked Jon Paden, of the Pilchuk Glass School, to bring his expertise in woodworking, especially old-fashioned joinery without using glue or nails. Bartow says, “I make things and [Paden] finds out how to put them together.”

The tops of the poles have extending parts, such as the Raven’s wings and the Bear’s arms. Paden designed joinery mechanisms to secure everything to the pole bases. He explains, “the wings of the Raven and the extra parts are not held together by glue or nails. The entire work consists of a series of interworking [parts] – mortise-and-tenon joints – that lock together.” Paden says, “I have done my job right if you don’t know I have done anything at all. My work is unseen.”

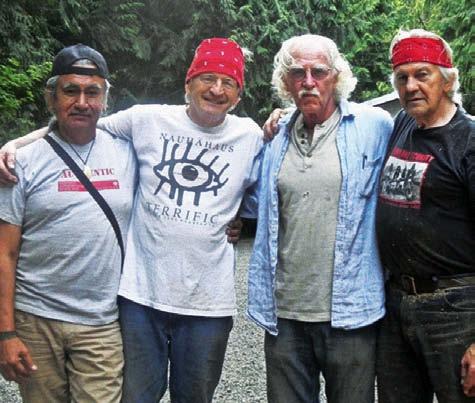

The cedar tree was secured from renowned carver Duane Pasco, who had the 400-year-old fallen cedar on his property. Pasco and his friends helped transport it from Poulsbo, Wash., to Newport. Then Pasco and fellow expert carvers Loren White and Joe David (Nuu-chah-nulth) stripped the bark and helped dress the logs. White spent two days hollowing out the backs of the poles. Paden explains that the core is removed because “a tree grows around a central post axis point. The post doesn’t have flexion so you need to remove the core, which allows the wood to move and expand.” Froelick obtained the boards for the back of the poles.

The pole bases have the same horizontal pattern. Bartow completed the pattern on one pole, and community members came to the studio to complete the second one. He explains that the origin of the pleated pattern “is not Oceanic or Northwest Coast or African, but it is South Beach [Oregon]. It [represents] the tides changing on the mudflats, where I dug clams and Booker [his son] and great-granddad dug clams. When you go clam digging, the water makes this shimmer; it vibrates.” Bartow also compares the pattern to the succession of generations. It symbolizes, he says, “the movement down to generations or up through the generations... like little waves.”

Since the Raven is tied to water, Bartow added carvings to that pole of the sun and moon which govern the tides. In working with an old-growth tree, Bartow and Paden discovered knotholes in the wood. Instead of patching them, Bartow carved animals, such as a bird, peeking out from them.

As an accomplished musician, Bartow likens his carving to the creation of music. The carving instruments like “chisels, hammers, [and] knives…creat[e] a rhythm.” A musical cadence emanates from the numerous hand tools in use every day. Bartow and the other carvers have been working with elbow and texture adzes and then crooked knives for detailing. Some of the tools were gifted to them, and others were made to fit their body measurements.

After carving, Bartow added a stripe of red ochre along the front of each pole. The color resembles the red used in North Pacific Coast and Maori carvings. The final step was applying a finishing matte to increase the poles’ resistance to water and corrosion. Over the late summer, the completed poles began their cross-country journey to the East Coast.

When the National Museum of the American Indian opened in 2004, many people referred to the museum project as a “return to a Native place.” It was a homecoming and reawakening of the indigenous presence along the National Mall. While the Bartow sculptures will seem to be a new addition to the Museum, they are carved from a foundation hundreds of years old and from a collaborative effort of old-fashioned strength and wisdom.