Walter Lamar was stunned when he heard that a cradleboard made by his great-grandmother Hush se ah was in the National Museum of the American Indian collection. His great-grandmother was his first memory, and he hadn’t seen her since he was about 4 years old. This was the only item of hers he knew to still exist.

Hush se ah was born in 1876 as a member of the Wichita Tribe of Oklahoma. Like many other Indigenous children at that time, she and her younger brother were sent to a government school. But soon after, a fire broke out there, killing him. Hush se ah’s parents brought her home and continued to teach her traditional ways. As a result, she never learned English, and as she raised Lamar’s father, Newton, and aunt Doris, they were among the last fluent speakers of the Wichita language.

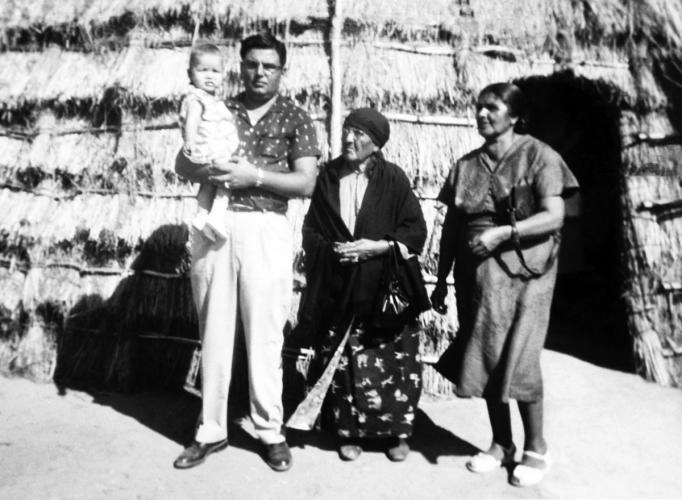

In 1909, Hush se ah’s husband, Wichita tribal member Walter Lamar, sold the cradleboard that had carried their daughter to anthropologist Mark Raymond Harrington, who was collecting objects for the institution that would later become the National Museum of the American Indian. In 2019, during a decade-long project to supplement the museum’s records, NMAI Curator Ann McMullen read a note that “Mrs. Walter Lamar” had made this cradleboard. After reviewing some census information, she reached out to the husband of NMAI Director Cynthia Chavez Lamar, who is also named Walter Lamar, and notified him. He immediately knew this was the name of his great-grandmother, but he didn’t rush to view the cradleboard. He said, “I needed to wait until I was emotionally ready to see it.”

A year later, Lamar, who is also Blackfeet, and Cynthia were guiding a Blackfeet tribal delegation through the museum’s collection at the Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Maryland. It was then Lamar saw the cradleboard for the first time. When he finally touched it, he said, “I just sobbed. I could feel the intense connection and it just coursed through me. It was so real, so palpable.”

Lamar is grateful that the museum has preserved his family’s cradleboard, a tether to the past. “One day, my kids and grandkids will come here and feel that same connection,” he said. “This is our identity. This is our history. This is our heritage.”

Lamar also encourages others, particularly Native language speakers and elders, to search the NMAI collection online (AmericanIndian.si.edu/collections/search) and provide additional information about these items. He said, “This is absolutely critical while we still have our knowledge keepers.”