In April 1918, the last year of World War I, Private First Class Leo McGuire was driving an ambulance to and from a field dressing station near Seicheprey, France, to retrieve wounded soldiers. McGuire was a member of the Osage Nation from Oklahoma and had enlisted when he was 19 years old. On one of his trips, a shell exploded near the ambulance, throwing it from the road. McGuire was knocked unconscious and when he awoke, returned to his duty station on foot. Although suffering from an injury in his back and not yet recovered from the shock, he still tried to return to duty that afternoon, but the medical officers insisted he wait until the following day. For his heroic actions, the U.S. Army awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest award for gallantry. He was the first U.S. soldier to receive this award.

At least 12,000 Native American, Alaska Native and Indigenous members of Canada First Nations served in World War I. Among them were ambulance drivers such as McGuire as well as officers, infantrymen, pilots, sailors, communications experts, nurses, cooks, musicians and others who served. Limited documentation and scattered sources have long made finding and recording their stories difficult, and the details of their service could have been lost to time. However, for the past eight years, the Sequoyah National Research Center at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock has been trying to acquire the stories of all of the known 12,000 Indigenous veterans who served in World War I and make these records accessible to their families, Native communities and other researchers.

Little Rock has a close connection with soldiers of World War I as its Camp Pike (now Camp Joseph T. Robinson) was one of the main training centers for soldiers from Arkansas and Oklahoma. Daniel Littlefield, the director of the research center, said, “That really made a name for us.”

Littlefield was a professor of English at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and the archive grew out of his desire to add Native American writings to his American literature classes. Yet no collection of such writings existed at that time. He and fellow English professor James Parins at the university began compiling a bibliography of Native authors and eventually published two volumes titled “A Biobibliography of Native American Writers.” From the materials they collected, particularly Native-published newspapers, they formed the American Native Press Archives in 1983.

As the archive had no budget, it was run by Littlefield, Parins and volunteers from 1983 to 2006. After securing a space and financial support from the university, the archive was renamed the Sequoyah Research Center in 1999 and then the Sequoyah National Research Center in 2008. Today, it has a staff of two and continues to be helped by student interns and volunteers.

The center has acquired the largest collection of Native-published newspapers and periodicals in the United States and has become the official archives of the Indigenous Journalists Association (formerly the Native American Journalists Association). Journalist Paul DeMain (Oneida)—who started the independent newspaper News From Indian Country in 1986 and served as its editor for 33 years—donated a large collection of his newspapers. The center’s archive is the “legacy of [Native] newspaper publishing,” DeMain said. “It will be able to tell the story [of Indian Country] as told by Indigenous people from as many perspectives as possible.”

Over time, many Native authors and others have donated a wide variety of materials about and by Native Americans to the archive at the center, including books, photographs, personal papers, transcripts of interviews as well as films, music and other video and audio recordings. Littlefield said, “We call it the world’s largest collection of Native expression. If they say it, write it, speak it, film it, sing it, we try to collect it.”

As the archive contained many records about Native veterans, in 2017, the center’s staff decided to create an exhibition about World War I Native American code talkers, the servicemen who used their own language to convey “coded” messages over radio transmissions. Yet they realized they were only one part of a far larger picture. Eventually, they collected and displayed the names of 2,300 Native veterans at the center.

Many Native soldiers of World War I were identified from Indian boarding school publications in the archive. Many of these schools put students through military-style training, including drills and how to handle riffles. “A lot of those guys went right out of boarding schools into the military,” Littlefield said. School publications often listed those who enlisted and published letters they wrote to the schools and their families while serving. One such letter from Robert Big Thunder (Ho-Chunk) was published in the 1919 Chilocco “Indian School Journal.” He describes his combat service, the use of Ho-Chunk language in “code talking” as well as the wounds he received and subsequent convalescence.

In 2019, the United States World War I Centennial Commission asked the center to help provide materials for its website. But once the commission concluded in 2020, the center decided it would endeavor to collect and curate materials about all the 12,000 Native World War I veterans. The center’s “Modern Warriors of World War I” database now has the records of more than 6,200 veterans and is continuously growing. In addition to contributions from families and other institutions, the center has partnered with Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology to obtain many records.

The files have revealed some surprises. For example, several Native veterans were musicians. Many wrote that their regimented training in boarding schools helped them in boot camp and adjusting to military life. Others described visiting historical sites in France that they had learned about in school.

The center is now digitizing its thousands of records so they can be available through a website, which is expected to be launched in 2026. The goal was “to preserve it, but not take it away from the communities,” said the center’s archivist, Erin Fehr (Yup’ik). While many studies focus on numbers and statistics, the database was designed to humanize the individual soldiers and show the communities from which they came. “So when a great-grandson wants to find out more about his great-grandfather’s service in World War I, he will be able to go onto our website and pull all of the material that we’ve been able to find,” Fehr said.

The collection is open to anyone conducting research but can offer much to Native peoples and scholars. Internships and graduate research opportunities have enabled Native students to help identify, organize and learn from the collections. “I feel like I’ve learned a lot about my ancestors,” said Charlie Smith (Cherokee), a public history graduate student. “This is something I can contribute toward and will help build up my future professional life.”

Choctaw author Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer relayed how a son’s account of his father Tushpa’s faith in God and resilience during the Choctaw Trail of Tears inspired her to write her novella, “Tushpa’s Story.” Sawyer said, “Without the Sequoyah National Research Center preserving and sharing this piece of history, I would never have known about Tushpa, and his journey might have remained lost.”

Judy Allen (Choctaw), executive director of public relations for the Choctaw Nation, used the collection to create a web-based digital archive about Choctaw veterans. She said, “Erin was generous with her time and records so that the World War I Choctaws could be included.” She said the center also provided information that helped the Choctaw Nation request medals of valor for some of its World War I soldiers.

“Our goal is to bring these men to life,” Fehr said, “to show they were humans just like you and I, and that they had families. They had hopes and dreams, and yet they set those aside to serve in the U.S. military.

Native Veterans of World War I

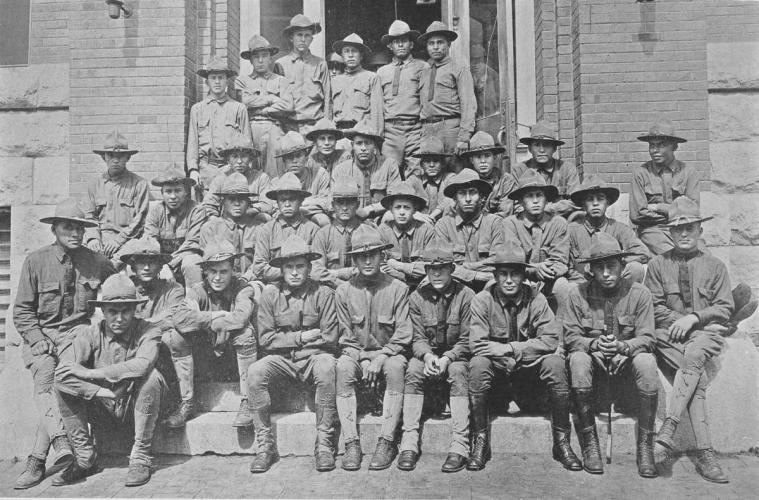

More than 12,000 Indigenous men and women served in a variety of roles in the U.S. military during World War I. They came from communities in Canada and across the United States. Each of their experiences before, during and after their service was unique. Here is a snapshot of just a few of the 6,200 veterans whose stories are recorded in the Sequoyah National Research Center’s collection.

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

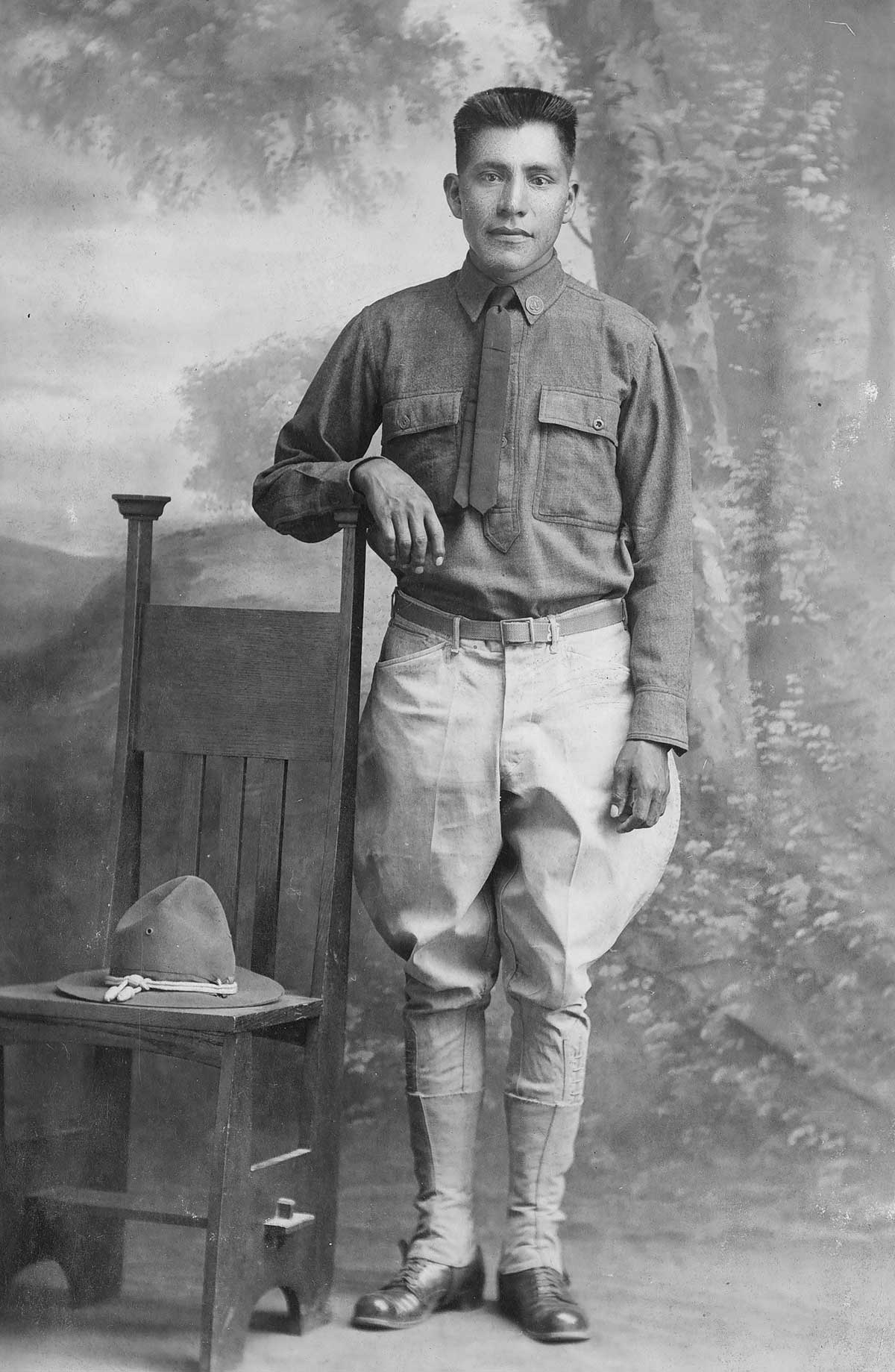

Private Calvin Nahoto Atchavit (Comanche)

Calvin Atchavit was born on June 20, 1893, in Indian Territory, along West Cache Creek near Faxon, which later became Cotton County, Oklahoma. Orphaned while young, he and his brother were raised by their aunts. He was working as a mechanic in Walters, Oklahoma, when he was drafted on April 25, 1918, and began his military training at Camp Travis, Texas.

On September 12, 1918, he was wounded in the battle of St. Mihiel, which was fought between American and German forces in northern France. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross “for extraordinary heroism in action” while serving with Company A, 357th Infantry Regiment, 90th Division, A.E.F. near Fey-en-Haye, France, on September 12, 1918. During the attack of his company, though he had been severely wounded in the left arm, Private Atchavit shot and killed one of the enemy and captured another. In another action, while laying land wire and cutting enemy communications and barbed wire in no man’s land, he became separated from his group. Getting into a skirmish he was wounded in the hip, but he was still able to return several days later with a German prisoner.

He distinguished himself in another battle, aided by his skills relaying messages in his Native language as a code talker. In 1919, the Oklahoma City Times published his picture and reported that the Belgian Government had given him a “WAR CROSS, for talking over the lines when they were TRAPPED BY THE ENEMY. His Comanche tongue helped get messages across that were not understood by the enemy.” Atchavit returned to the United States on June 5, 1919, and was discharged June 16, 1919.

After the war, he and his wife, Sarah Passah, were farmers in Cotton County, Oklahoma. He died on October 9, 1943, at age 50 and is buried at Highland Cemetery in Lawton, Oklahoma. In 2012, the Comanche Indian Veterans Association posthumously awarded Atchavit the Numu Pukutsi (Comanche Contrary Warrior) Award.

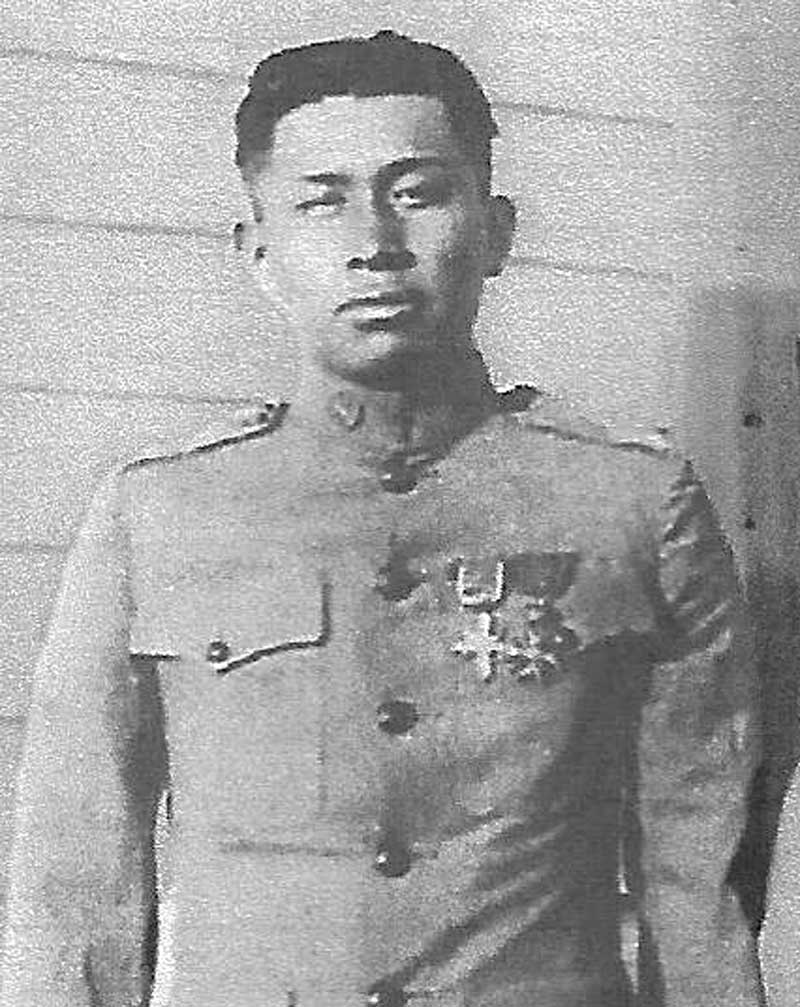

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

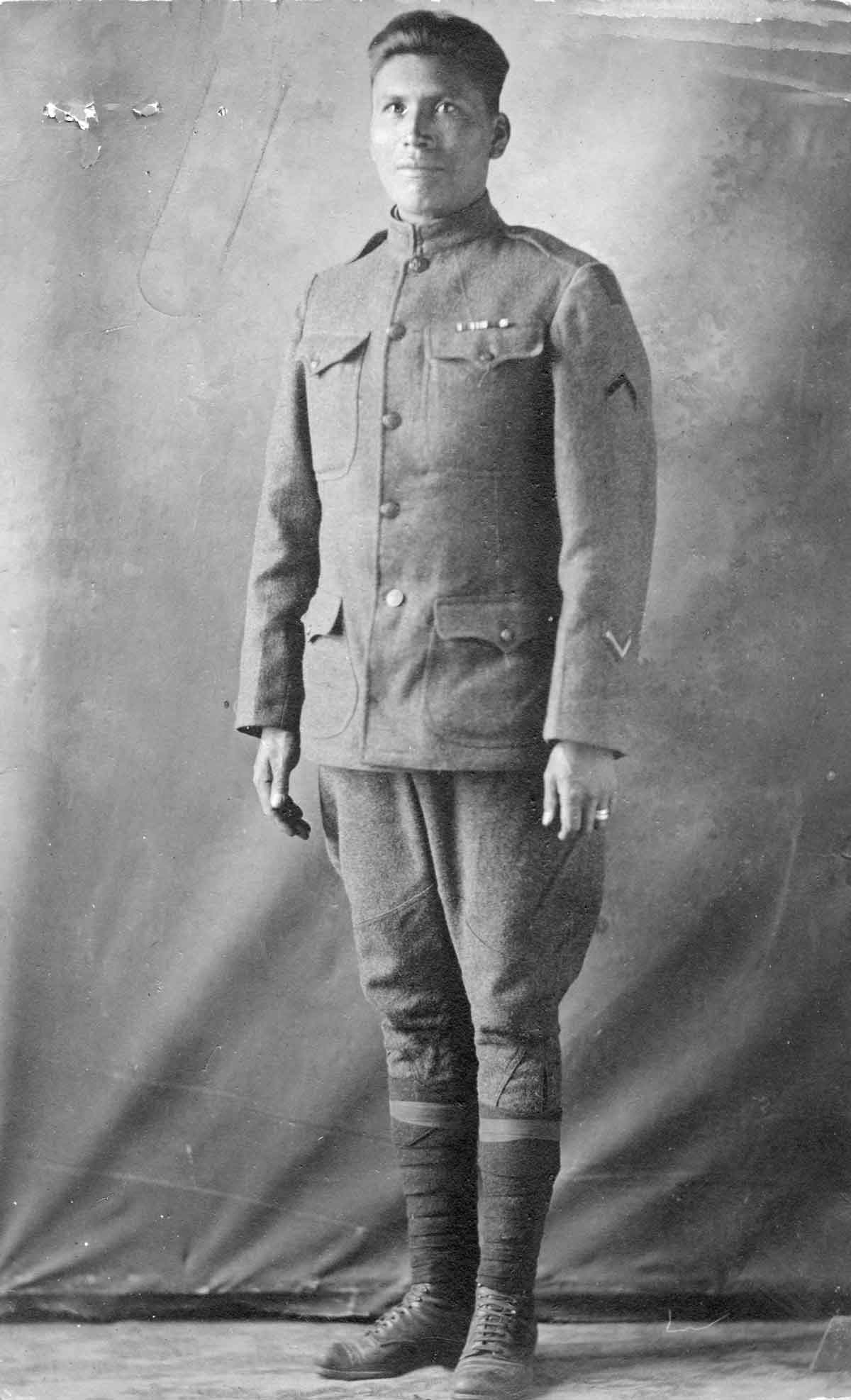

Private Albert Grass (Standing Rock Lakota)

Albert Grass (Hehaka Mani [Walking Elk]) was born February 7, 1897, at Cannon Ball, North Dakota. He was the grandson of Chief John Grass and served as the last Dakota Sioux hereditary chief. He was the first Sioux soldier to enlist in Company I, 2nd North Dakota. Soon a private in Company A, 16th Infantry, 1st Division, Grass gained distinction as a dispatch runner and scout. He also served as a code talker, using his Lakota language. As a 1921 news article in the collection reports, “When Germans cut in on the ground wireless or telephone lines from listening posts, it was Grass and Richard Blue Earth, another Sioux who was killed in action, who communicated in the Sioux language between the outposts and the command headquarters to the utter confusion of the Huns.”

After avoiding German machine-gun fire, Grass was killed while attempting to get water for his comrades by a bomb dropped from a German plane on July 20, 1918, during the Battle of Soissons in northern France. When his body was returned in 1921, his elaborate funeral was attended by more than 3,000 people, including members of the men’s warrior society the White Horse Riders, an American Legion Post and a Catholic church.

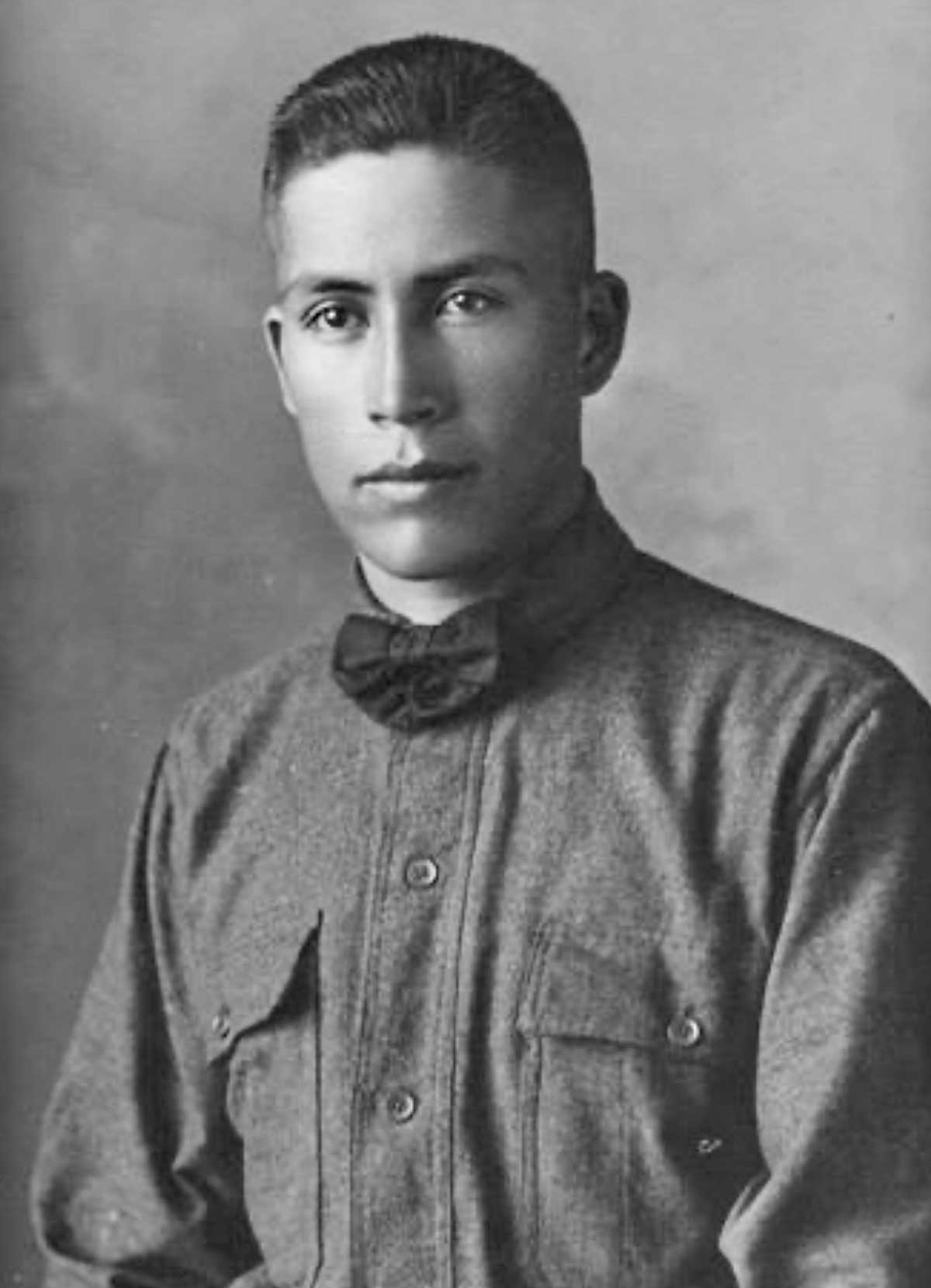

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

Corporal Otis Leader (Choctaw/Chickasaw)

Otis Leader was born March 6, 1882, near Scipio in Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. At the age of 34, after U.S. federal agents mistook him for a “Spanish Spy” in 1917, he wished to show his willingness to defend his country and so enlisted in the U.S. Army. He would serve as a corporal in Company H, 16th Infantry, 1st Division. After an artillery round killed his entire gun crew at Chateau-Thierry, Leader armed himself, flanked two “machine gun nests” and captured 18 German prisoners. He was wounded twice and poisoned with chemical gas twice.

He participated in the battles of Cantigny, Soissons-Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel, Verdun, and the Argonne Forest. While convalescing at a hospital in France after being gassed, he was called upon to continue to serve as a code talker, communicating military messages in Choctaw to those in battle.

In Paris, French painter Raymond Desvarreux chose Leader for the subject of a portrait as the “Ideal American Doughboy.” U.S. General John Pershing called Leader one of the war’s “greatest fighting machines.”

For his outstanding service, Leader received two French Croix de Guerres, two Silver Citation Stars, the Purple Heart with clusters and several other awards. After World War I ended, he worked in several positions for the Oklahoma State Highway Department and was active with American Legion Posts. Leader died on March 26, 1961.

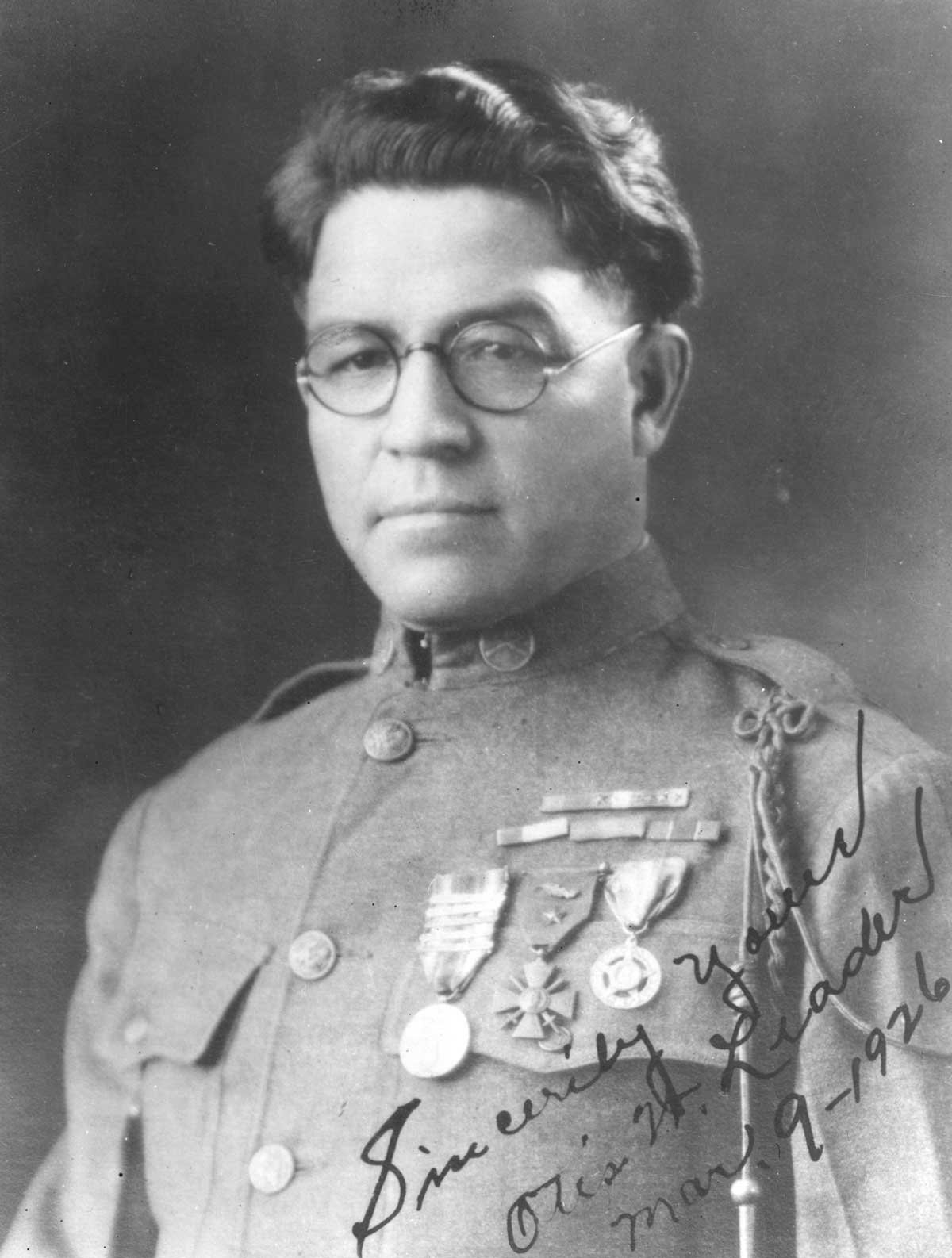

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

Musician 1st Class Guy Maktima (Hopi)

Guy Maktima was born on October 27, 1891, and grew up in Mishongnovi Village on the Hopi reservation in Arizona. As a high school student, he attended the Sherman Institute, an Indian boarding school in Riverside, California, where he was a noted long-distance runner, a member of the cross-country team and tried out for the 1912 Olympics.

He later graduated high school from the Phoenix Indian School, where he enlisted in the Arizona Army National Guard’s 1st Infantry, Company F. From May 13 to October 26, 1916, he joined 28 other American Indians for border patrol duty at Naco, Arizona, to search for Mexican revolutionary Francisco “Pancho” Villa, who was being pursued by General John Pershing.

In 1918, his unit was activated for service in World War I. The company was reorganized and became the 158th Infantry Band, which included five other American Indians and Maktima, who played trombone. They served in France from August 1918 to April 1919. Playing throughout the French countryside, Maktima and his fellow Native soldiers were thought of as curiosities as many French had never seen American Indians before. On Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, the band performed at many celebrations. The next day, Maktima was promoted to Musician 1st Class. That December, the band performed for U.S. President Woodrow Wilson at the American ambassador’s house in Paris.

In April 1919, he returned to New York and was honorably discharged on May 3, 1919. He died on December 16, 1985.

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

Private Robert Frank “Chief Rekwoi” Spott (Yurok)

Robert Spott was born in 1888. He came from the Yurok village of Requa (Rekwoi) in northern California. Within six months, Spott went from peaceful fishing on the Klamath River to fighting in the trenches of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in France. He served as a message courier in the U.S. Army’s 111th Infantry Regiment, 28th Division, and later in the 40th Division.

Spot received the French Croix de Guerre with Palm for rescuing a wounded French general. Later he was poisoned by a chemical gas during a battle in Bordeaux and was hospitalized for a year in France following the war.

Spott went on to serve as the chairman of the Yurok Tribal Council and president of the California Indians Association. He also became an anthropologist and worked closely with Alfred Kroeber, with whom he was lead author on the 1942 publication “Yurok Narratives.” Spott is responsible for much of the early ethnography about the Yurok people.

Spott would continue to be a leader in his Native community for several decades. He died on August 28, 1953, in Crescent City, California.

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

Musician 2nd Class Isaac Sequajaw Willis (Little Traverse Ottawa)

Isaac Sequajaw Willis was born December 10, 1897, near Charlevoix, Michigan bordering Lake Michigan. He attended Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania from October 1913 to June 6, 1917. Willis enlisted in the U.S. Navy in Philadelphia the next day at the age of 19. He served on the USS Kentucky, a training ship designed for coastal defense that operated along the East Coast.

Having played music at Carlisle, Willis served as a Musician 2nd Class. While in the Navy he wrote several letters to Carlisle School Superintendent James Francis Jr. to thank him for sending him issues of the school’s “Carlisle Arrow and Redman.” Willis tells him about other former Carlisle students in service and even apologizes for missing the 1918 graduation due to his military service. Willis also commented on the excellent food and clean quarters as well as his joy in crossing the Atlantic Ocean. He noted how well the musicians were treated by the other sailors and that the captain sent them a box of candy. In his letter he wrote, “I will never regret joining the Navy.”

Willis was honorably discharged September 11, 1919. He died April 29, 1957.

During World War I, at least 14 Native American women are known to have served as nurses in the Army Nurse Corps and the American Red Cross in France and the United States. Information about many of them is archived at the Sequoyah National Research Center.

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

2nd Lt. Ruth Cleveland Douglass Counihan (Mille Lacs Chippewa)

Ruth Cleveland Douglass was born March 28, 1893, in Brainard in northern Minnesota, and later attended Pipestone Indian School at Pipestone in southwest Minnesota. She enlisted as a nurse for the U.S. Army on January 16, 1918. She spent eight months at Camp Pike in Arkansas before being sent to Bazoilles-sur-Meuse, a commune in France that was being used as an evacuation hospital. After spending 10 months in France she returned to the United States, where she worked at General Hospital at Fort McPherson, Georgia, for 15 months and then at Station Hospital in Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, in September 1920.

Douglass experienced many challenges during her service. On the third day of her voyage to France on the USS Leviathan, an influenza epidemic broke out. By the time they reached France, 80 soldiers and two nurses had perished. She later worked in pneumonia, surgical and other wards, and following the Armistice, helped decorate and distribute Christmas presents and wine to convalescing soldiers. Tending wounded in France, Douglass recalled, “The first thing a nurse puts on in the morning is a ready smile. The boys responded splendidly.”

Douglass wrote about her time in service in 1919: “I am not a regular Army Nurse, but came in as a War Emergency Nurse.” She commented, “Contrary to public opinion, the emergency still exists.”

Douglass married Patrick Sheahy on March 13, 1922. After his death she married James F. Counihan on June 26, 1930. She died on January 13, 1965, in Portland, Oregon, at the age of 71.

Courtesy of Sequoyah National Research Center

2nd Lt. Lula Leta Owl Gloyne (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians)

Lula Leta Owl was born December 27, 1891, in North Carolina. She graduated from the Hampton Institute, a university historically dedicated to educating Black and Native American students, in 1914. She then obtained her nurse’s training at Chestnut Hill Hospital School of Nursing in Philadelphia, graduating in 1917 and becoming the first Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians registered nurse.

Owl was a nurse on staff at St. Elizabeth’s Episcopal School on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in South Dakota when a call went out for nurses to serve in World War I. She volunteered for overseas duty, but unable to pass the seaworthy exam due to extreme seasickness, was sent to Camp Lewis, Washington, where she served for the duration of the war.

Owl was the only Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians officer in World War I, serving as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps. She secretly married Jack Gloyne in 1918 (even though it was forbidden, as she was an officer and he an enlisted man). The couple went on to have four children.

After the war, Gloyne served as a U.S. Indian Health Service field nurse in South Dakota, North Carolina and Oklahoma. She was also instrumental in the founding of the first hospital for her Cherokee people in 1937. In 1943 she was declared a “Beloved Woman” (Ghigau) by her tribe, a prestigious Cherokee title historically bestowed on women who demonstrated exceptional leadership or contributions to her community or great heroism in battle. She died April 17, 1985, at age 93. In 2015, she was inducted into the North Carolina Nurses Association Hall of Fame.