When Captain George Waymouth explored the coast of Maine in 1605, he made a point of kidnapping five of his friendly Abenåaki hosts and taking them back to England, along with their bows and arrows and bark canoes.

Waymouth was following European procedure, standard from the time of the Vikings. The captives were prized, not only for display and proof of a successful voyage, but as potential interpreters, sources of intelligence and possibly even Christian converts. Yet Waymouth’s group was exceptionally important, although now famous for the wrong reason.

In remarkably widespread misinformation, some historians, and apparently all of the Internet, believe that one of the captives was the famous Squanto, or Tisquantum, the go-between for the Plymouth Bay Puritans 15 years later. Wikipedia compounds the crime by saying the other abductees were members of his tribe.

Both statements are demonstrably false. Tisquantum was from the village of Patuxet, now the site of Plymouth, Mass., some 200 miles south of Waymouth’s landings and part of the Pokanet or Wampanoag federation in what is now southeastern Massachusetts. Its great chief was the Massasoit. The real abductees were eastern Abenaki, part of a federation led by Bashebas, a major figure mentioned in English and French sources, whose seat was near what is now Bangor, Maine. There is no contemporary record placing Squanto anywhere near Maine in 1605. Yet we know the names, and a fair amount of the history, of the Abenaki who were kidnapped. It is their story, full of swashbuckling international intrigue, that concerns us.

Waymouth’s Victims

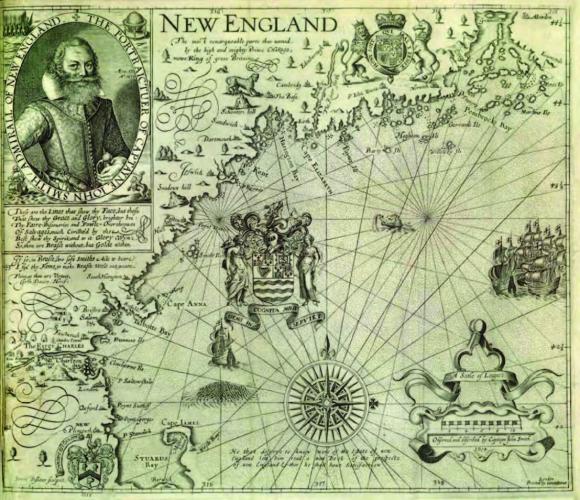

Standard histories give the impressions that American history starts with Jamestown, or Henry Hudson or the Puritans at Plymouth. But North American Natives had been running into Europeans for most of the preceding century. Fishing boats from Basque, French and west English ports had been working the Grand Bank cod schools by the hundreds, calling at the Labrador and Newfoundland coasts. Exploration and settlement attempts dated from the early 1500s and had accelerated after Queen Elizabeth’s break with Spain and the defeat of the Armada in 1588. The coast of New England was already familiar by the dawn of the 1600s. (John Smith, leader of a major exploration in 1614, complained it was becoming too crowded with European shipping.)

One of the most important, but relatively ignored, of the early explorations was the visit of Captain George Waymouth in 1605. The voyage was highly successful for science, less so for profit. It made speedy passage, scouted good harbors and gathered a wealth of intelligence. It could easily have resulted in the first permanent English settlement in North America, except for a major political problem.

The venture was heavily backed by Catholic interests, looking for a refuge for religious exiles. But just as it returned with a promising report, a group of Catholic extremists were plotting to assassinate King James I and most of Parliament. The group had discovered it could rent a storage space in the basement of the Parliament building, and filled it with gunpowder covered with firewood. The infamous Guy Fawkes, he of the ridiculous thin mustache and pointed goatee, guarded the stash and was arrested there November 5, just before the detonation. The explosion of the Gunpowder Plot whipped up an anti-Catholic fervor that quashed support for Waymouth’s follow-up expedition. (One of Waymouth’s main backers was briefly arrested as a possible conspirator.)

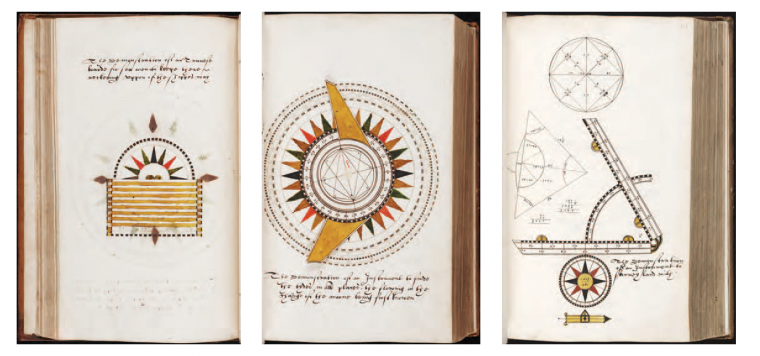

The expedition did have two lasting results, a thorough and competent report by crew member James Rosier and the kidnapping of the five Abenaki tribesmen. The abductions, said Rosier, were in fact a main goal of the trip, “being a matter of great importance for the full accomplement of our voyage.” From first contact in Penobscot Bay, the crew accustomed Natives to coming on board with enticements of gifts and English food. The English and Abenaki traded and exchanged visits for several days. Then, as almost always happened, the mood changed.

At a rendezvous for trading, a scout for the crew reported a large number of well-armed tribesmen had gathered with no sign of trading furs. Said Rosier, “We began to joyne them in the ranks of other Salvages, who have been by travellers in most discoveries found very treacherous; never attempting mischief, until by some remissnesss, fit opportunity affordeth them certaine ability to execute the same.” (It never seems to cross the Europeans’ mind that their own conduct might have caused the change in attitude.)

The crew turned back and determined to take whatever hostages they could before suspicions spread. The next day, two canoes with three men each came to the ship, including a regular visitor “of a ready capacity” that Waymouth and Rosier had already marked to take back to England. Three came on board. To round up the others, Rosier went on shore with a box of merchandise and a plate of peas; two of the tribesmen sat with him, and the English crew jumped them, wrestling them into the long boat by grabbing their long hair. Waymouth also took their canoes and all their bows and arrows, storing them carefully for the voyage.

By chance, the captives were more important than the English at first realized. Their leader, Nahanendo (also spelled as Tahanendo and Tahando, among others), was sagamore of the region and a close relative of Bashabes, the chief of the Abenaki confederacy. The great chief tried urgently to rescue his tribesmen. As Waymouth continued to explore up the river, Bashabes sent canoes repeatedly, offering to trade large quantities of fur and tobacco. “This we perceived to be only a mere device to get possession of any of our men,” wrote Rosier, “to ransome all those which we had taken.”

Waymouth shortly turned back for England, realizing that his most valuable cargo were the five captives below decks. Rosier turned his efforts to restoring good relations with the bewildered former friends. “Although at the time when we surprised them, they made their best resistence, not knowing our purpose, nor what we were, nor how we meant to use them; yet after perceiving by their kind usage we intended them no harme, they have never since seemed discontented with us.”

Rosier was apparently in charge of their debriefing, and by his account it went very well. He called them “very tractable, loving, and willing by their best meanes to satisfie us in any thing we demanded of them, by words or signes for their understanding.”

“We have brought them to understand some English, and we understand much of their language; so as we are able to aske them many things.”

Among other things Rosier learned their names, although not how to spell them. In addition to Nahanendo, the sagamore, he identified three as “gentlemen,” Amoret, Skicowaros and Maneddo, and a “servant,” Assacomoit. (Variant spelling are listed in the Cast of Characters, see page 34, but none of them remotely resemble Squanto or Tisquantum.) They told him that their homeland, the territory of Bashabes, was called Mawooshin.

The Mawooshin Five

As soon as they set foot in England, it was clear that the Mawooshin Five were a valuable source of intelligence. They became the target of international intrigue. Rosier reports that “some forrein Nation (being fully assured of the fruitfulnesse of the countrie)” was trying to involve Waymouth “in conveying away our Salvages,” a plot “which was busily in practice.” The likely party was Spain; although it couldn’t prevent other countries from encroaching on its claim to North America, it did its best to spy on what they were doing. The still murky plot failed, but Rosier decided to keep secret most of what “his Salvages” had taught him, including a list of 400 to 500 Algonquian words.

Domestic intrigue also intervened. With the collapse of the coalition backing Waymouth, a new grouping of businessmen stepped into the void, obtaining a royal charter for a Virginia Company. The new endeavor had two branches. A London grouping concentrated on a new settlement at Jamestown. West County entrepreneurs from Bristol and Plymouth made plans for “North Virginia,” exploiting the Mawooshin captives.

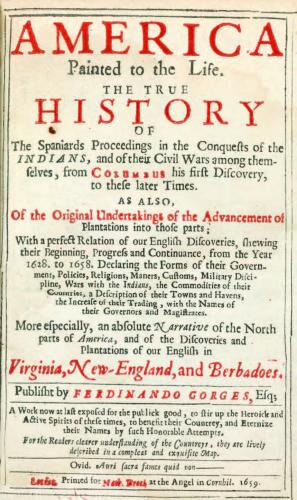

The apparent Spanish plot against “our Salvages” must also have raised concern about the security of Nahanendo and his party. They wound up as “guests” of two of the best-guarded figures in England, the Lord Chief Justice John Popham and the commander of the fort at Plymouth, Sir Ferdinando Gorges. Popham, with a “Hanging John” reputation for severity, had served on the tribunals that condemned Mary Queen of Scots and Guy Fawkes. Gorges, a veteran of European wars, had played an apparent double role in the attempted coup of the Earl of Essex against Queen Elizabeth, saving Popham from the conspirators. Their new association with the Abenaki decisively turned their interests westward.

Gorges was very taken with his house guests, whom he called Maneday and Assacomet. (These are clearly two names from Rosier’s account. The confusion about Tisquantum/Squanto comes from one sentence in a late memoir, in which Gorges or a posthumous editor inserted the Wampanoag’s name in the list.) He praised the Abenaki for “great civility farre from the rudeness of our common people” and talked with them at length about their homeland. “And the longer I conversed with them, the better hope they gave me of those parts where they did inhabit, as proper for our uses.”

Their information included “what great Rivers ran up into the land, what men of note were seated on them, what power they were of, how allyed, what enemies they had, and the like of which in his proper place.” This intelligence fed into a briefing paper now known to historians as “The Names of the Rivers;” it was found in a cache of 17th century English state papers in the early 1900s and revisited as a fresh source as late as 2007. The Mawooshin Natives were very likely induced to be forthcoming by the hope of returning home. Both Gorges and Popham attempted to make good on the promise.

The Richard Affair

By the end of the next summer, in August 1606, the two Abenaki lodged with Gorges sailed from Plymouth on a ship called the Richard, captained by Henry Challons and bound for “North Virginia,” their home Mawooshin. (The account printed in Purchas His Pilgrimes in 1625 spells their names Mannido and Assacomoit, but they are still clearly the people in question.) Popham and Gorges, with a group of West Country investors, stocked the ship with 12 months of supplies and men willing to stay in America. It was their bid to beat Jamestown as the first permanent English settlement in North America, and the Abenakis’ chance to go home, but it ended in a complex diplomatic disaster.

The trouble began when the captain ignored Gorges’ instruction to take the direct northern route used by Waymouth. (Gorges argued that the Indian passengers could serve as pilots along the Maine coast.) Like more timid mariners, Challons sailed south to the Canaries and then west to the Caribbean before coasting North. The route was much longer and fraught with delays. After adventures in the West Indies, the Richard headed north in a great storm, and on a foggy morning in November suddenly found itself in the middle of a Spanish fleet. With three sails to the windward and more ships emerging from the mist to the lee, Captain Challons had no chance to flee. As Spanish fire shredded his mainsail, he hove to and instead sought to explain himself to the Spanish admiral.

Even though Spain was then formally at peace with England, the Spaniards were in no mood to listen. A boarding party armed with swords and half-pikes roughed up the English sailors. Assacomoit took the worst wounds. He was stabbed “most cruelly several places in the body and thrust quite through the arme,” reported John Stoneman, pilot of the Richard. Panicked and baffled, “the poor creature” had tried to hide under a locker. As the Spaniards stabbed at him, “he cried still, ‘King James, King James, King James his ship, King James his ship!’”

Assacomoit had apparently been misinformed about the extent of the English monarch’s influence. The Spaniards seized the ship’s supplies as spoils. They divided the 30 crewmen among their own vessels and took them back to Seville, commencing months of protests, lawsuits and pleas for the release of the English, and the Abenaki.

Gorges wrote an over-optimistic letter to Captain Challons in March, urging him not to accept a settlement of less than 5,000 pounds for damages. “For you knowe that the journey hath bene noe smale Chardge unto us that first sent to the Coast and had for our returne but the five salvadges whereof two of the principall you had with you.” But as the affair dragged on, Challons and Gorges lost touch with the Abenaki. “The Indians ar taken from me and made slaves,” Challons replied in June. Weeks later, the captain wrote Popham that he was forbidden to speak “with the naturals.”

“They will eyther Convert them or by Famine Confounde them for they ar almost Starved already.”

As months dragged on, diplomats at the highest levels debated free access to the Indies and the Richard’s crew complained from the prison in Seville that they had been forgotten. But there were hints of a deeper game behind the delay, with the Abenaki as a prize. Stoneman, the pilot, wrote that after three months he won some freedom for his mates as the Spanish realized the extent of his experience in “North Virginia.” As a veteran of Waymouth’s expedition, he might have been a target of the earlier plot that Rosier had mentioned. As a captive, he was now under intense pressure. “The Spaniards were very desirous to have me serve their state, and proffered me great wages, which I refused to doe.”

Seville merchants and officials asked him to make “descriptions and Maps of the Coast and parts of Virginia,” he wrote, “which I also refused to doe.” In and out of prison as the pressure increased, Stoneman finally received a warning from a friendly Dutch merchant. The Dutchman had learned from a local judge, said Stoneman, “that the Spaniards had a great hate unto me above all others, because they understood that I had beene a former Discoverer in Virginia, at the bringing into England of those Savages.” Because he wouldn’t enter their service or give them any useful information, they now planned to put him to torture. Rather than “stand to their mercie on the Racke,” Stoneman and two of his companions fled from Seville the next morning, leaving Challons, the rest of the crew and the Indians behind.

With these stakes in play, it seems unlikely that the Spaniards had simply seized Maniddo and Assacomoit for galley slaves. In fact, they had already indicated to Challons that they planned to convert, or reconvert, the Abenaki. It is very likely the Spanish government also meant to exploit them for intelligence, as the English had done.

What did finally happen to these two of the Mawooshin Five? Gorges reports that he finally “recovered” Assacomoit, possibly when the Spanish released the rest of the crew. His “old servant” returned to his household and helped him debrief a new captive, the famed Epenow from Martha’s Vineyard. Gorges adds a convincing detail: the two had difficulty understanding each other at first, since they spoke different dialects, albeit of the same language. In 1614, according to Gorges, Assacomoit sailed with the ship that returned Epenow to Martha’s Vinyard, but that is another story.

We simply don’t know what happened to Maniddo. But perhaps some day a debriefing file will emerge from the depths of the Spanish archives with news about his fate.

Return to Sagadohoc

The seizure of the Richard was a major loss for Gorges, but Lord Chief Justice Popham was determined to push forward. Shortly after Challons sailed, Popham dispatched his own ship to resupply the projected colony. Challons wasn’t at the rendezvous, so the ship explored the coast and chose a site, Sagadohoc, for the colony.

This expedition, led by Thomas Hanham and Martin Pring, was highly important but we know little of its details. The travel anthologist Samuel Purchas said he had prepared Hanham’s journal for publication but left it out to save space. It has since disappeared. We can deduce, however, that Hanham had returned Nahanendo home.

The colonial expedition proper, led by Captain George Popham (nephew of the Chief Justice) and Raleigh Gilbert (son of the famous Humphrey) arrived in Maine the next year, 1607. Nahanendo (or Nahanada, in its account) was waiting to meet them. Skicowaros (or Skidwarres) arrived with Popham and Gilbert and translated for them.

In the year since his homecoming, Nahanendo had regained his leadership position in his tribe. He now played a crucial, if ambiguous role, in relations with the new settlement. George Popham reported to King James that Nahanendo had spread word among the Natives about the King’s virtues, so that “among the Virginians and Moassons [Mawooshins] there is no one in the world more admired.” Nahanendo apparently was fighting a propaganda campaign against the local deity Tanto, “an evill spirit which haunts them every Moone.” Tanto’s adherents were warning the tribesmen not to have dealings with the English.

But Nahanendo was playing a double game in his own dealings with the colony, or so Gorges ultimately concluded. Nahanendo and Skidwarres promised rich trade with the Bashebas, and produced several high-level relatives of the chief, but a face-to-face meeting with the great chief never happened.

Reporting to the King’s minister in February 1608, in an apology for the poor return from Sagadohoc, Gorges blamed the Abenaki returnees. “They shew themselves exceeding subtill and cunning, concealing from us the places, wheare they have the commodityes we seeke for, and if they find any, that hath promised to bringe us to it, those that came out of England instantly carry them away, and will not suffer them to com neere us any more.”

If Nahanendo had learned in England that the settlers needed to show a profit to make the colony last, he had calculated shrewdly and successfully. Three deaths eliminated the colony’s leadership, those of Justice Popham in England, George Popham in Maine and the older brother of Raleigh Gilbert, which gave him an inheritance to go home to claim. Discouraged by the poor payoff, internal dissension and a bitingly cold winter, the Sagadohoc settlers packed up and went home. The Popham interests continued to send ships to trade, but for a while longer the Natives controlled the terrain.

Did the Abductions Work?

The strategy of kidnapping Natives might have reached a peak with the Mawooshin Five, but it showed itself to be double-edged. Waymouth’s captives did provide extensive information and linguistic skills that smoothed contact with the English. Ten years later, John Smith listed as one of his colonizing assets “my acquaintance with Dohoday [another permutation on Nahanendo], one of their greatest Lords, who had lived long in England.” But the Abenaki also learned significant lessons about the English. Above all they learned what the English wanted from their settlement at Sagadohoc, and how to frustrate it.

As Europeans were rapidly learning, a significant portion of their repatriated abductees, like Epenow, emerged as implacable and well-informed enemies. Although perhaps not as subtle as Nahanendo in attacking the economics of the colonial ventures, abductees up and down the coast became the core of resistance to the intruders.