When Paula Peters was in first grade, her teacher told her class about the “first Thanksgiving.” This version of the tale was similar to what teachers across the United States had been telling for decades: this was the first time Pilgrims, who had come to this country from England to seek religious freedom, shared a meal with friendly Indians. These Native Americans were the Wampanoag people, and Peters thought with pride: “Hey, that’s great. They’re talking about my ancestors.”

But then the teacher said, after their famous meal, “all the Indians died of a horrible plague.”

“Wait a second,” thought Peters, “we’re still here!” She knew from her family stories and cultural practices that Wampanoag people such as her were still living in her community of Mashpee as well as those of Aquinnah, Assonet, Chappaquiddick and Herring Pond in what is now Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island.

That teacher’s misconceptions were hardly unique. The “traditional” Thanksgiving tale taught in American schools and repeated annually over the remains of holiday turkeys goes something like this: Pious English Pilgrims sailed across the Atlantic in 1620 and landed at Plymouth Rock in December. The Pilgrims nearly starved, until they encountered American Indians who taught them how to grow corn, beans and squash. In the fall of 1621, the grateful Pilgrims invited the Indians to the first harvest celebration, which, thanks to President Abraham Lincoln’s attempt at national unity in 1863 amid the country’s Civil War, became known as the country’s Thanksgiving holiday.

Well, not exactly. Who is represented in written history often depends on who is writing it, and the standard story of the “first Thanksgiving” has generally been told by non-Indigenous peoples. The actual story of the Wampanoags’ encounter with the colonists is much more complex, with some devastating outcomes.

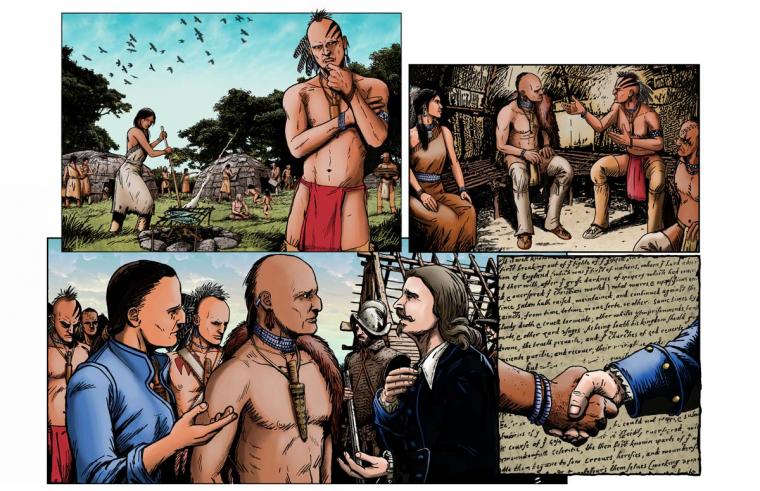

To help educators tell a more complete and accurate portrayal of this time in history, the National Museum of the American Indian’s education initiative, Native Knowledge 360° (NK360°), collaborated with members of the Wampanoag Nation to create an educational resource entitled “The ‘First Thanksgiving:’ How Can We Tell a Better Story?” Its lessons feature engaging illustrations and videos that include reflections from Wampanoag people about this historic event and how their views of it have been absent from the narrative.

They reveal, for example, that written accounts do not describe the colonists landing on a “Plymouth Rock” but rather coming ashore on a muddy Cape Cod. The Wampanoag people and neighboring Native nations were interacting with European explorers, traders and enslavers for nearly 100 years before English colonists settled at the Wampanoag village of Patuxet in 1620. After careful observations and negotiations, they did decide to help the English travelers. In the fall of 1621, after hearing shots from guns the English were firing in celebration of their harvest, about 90 Wampanoag men came to see what was happening. They then left and hunted for deer to contribute to the feast, to which, contrary to colonial paintings that portrayed Native women attending, only men were present.

“The event was more about diplomacy than a feast,” said Nichelle Garcia (Winnemem Wintu), an education specialist at the NMAI. The Wampanoag people were devastated from 1616 to 1619 by the “Great Dying,” a wave of infectious disease brought by earlier European traders and fishermen that killed approximately 90 percent of the Indigenous population along the Northeast Coast, including about 75 percent of the Wampanoag in the north and coastal villages. This left the Wampanoag people more vulnerable to attacks by the neighboring Narragansett Nation. When the colonists wanted to farm on Patuxet, the Wampanoag negotiated to allow them to use it. Only the English renamed the village “Plimoth” and claimed it as theirs.“The English were not sailors or traders,” said Garcia.“They were colonists, planning to stay.”

The Wampanoag Nation eventually signed a mutual protection treaty with the colonists, which the colonists saw as a guarantee the Wampanoag people would protect them while granting them more power. Even so, the treaty was short-lived and more colonists continued to move onto Wampanoag lands.

Linda Coombs, a knowledge keeper for the Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe and the program director of its Cultural Center, served as a consultant for the NK360° resource.“Both the Wampanoag Nation and colonists held harvest celebrations,” said Coombs. “But the Wampanoag people had and still have a deep knowledge of tending to the land and a reciprocal relationship with all living beings.”

“They have daily and seasonal rituals of giving thanks, not one holiday,” added Garcia.“Expressing gratitude to the world that sustains you is a way of life.” The Wampanoag give thanks to the natural world from which they draw sustenance year-round as they hunt, fish or gather traditional foods such as the cranberries they celebrate during their fall Cranberry Day festival.

The museum’s free online resource about Thanksgiving is what “teachers were looking for,” said Peters. She and her son, Steven Peters, founded SmokeSygnals, a media and museum exhibit production company. She, a Wampanoag historian, helped review the online resource and he produced video for it. The resource was created for third to fifth grades but can be adapted for sixth to 12th grades. The resource is inquiry based, meaning the students are given a set of questions and the sources to research their answers. “The goal is asking students to think about what they’re studying and come to their own conclusions, not telling them what to think,” said teacher Susannah Remillard, who tested the lessons with sixth graders and teaches the “Earthkeepers” class at Nauset Middle School in Orleans, Massachusetts.

“Hearing and understanding American Indian history from Indigenous perspectives provides an important point of view to the discussion of history and cultures in the Americas,” said Remillard. The lessons reflect “a long, thoughtful and deliberate process by NMAI to make these materials accessible for teachers, and this gives us confidence for use in the classroom—that’s a real gift.”

These teaching resources “make it easier to teach the real history. It will also help us understand our own history,” said Peters. “It’s different now, but there’s still a lot of work to be done.”