Virgil Ortiz still remembers the outings he took as a 6-year-old boy with his mother to creeks throughout their Pueblo of Cochiti in New Mexico. There, they would gather clay to mold into pots and storytellers—seated comical human or animal figures. His father was a drum maker and his mother and grandmother were both potters. He remembers giving prayers of thanks to Mother Earth for providing clay, a medium through which they could express themselves. “I was surrounded by art every day,” says Ortiz.

While much of the traditional Pueblo storyteller pottery was later made for the tourist trade, it is forged from a deep history—the Spanish colonialization of areas of the Southwest during the later 1500s and 1600s.

“When the first invaders first arrived into the area, a bunch of the artwork was broken and destroyed, lost. The Indigenous people were accused of sorcery and witchcraft, making all these different types of artworks,” said Ortiz. “The Catholic religion [was trying to] stamp out everybody and convert them into Catholicism. All the Indigenous people were enslaved, and all these different people started moving into the Pueblos.”

After the Spanish governor of New Mexico ordered Pueblo holy men whipped or executed, a Pueblo leader named Po’pay led a successful revolt in 1680, which kept the Spanish out of the state for 12 years. “We fought back,” said Ortiz. “That’s how the Pueblo Revolt took off. It pulled everybody together.”

The Pueblo Revolt’s success was instrumental in keeping many Pueblo cultural teachings, languages and artforms alive. The Pueblo peoples started making pottery again, and Ortiz has dedicated his artistic career to perpetuating its revival.

Ancestral Memories

Robert Gallegos, an avid Albuquerque collector of Cochiti Pueblo pottery since 1975, used to buy art from Ortiz’s mother and grandmother at the family’s booth at the Santa Fe Indian Market. He discovered Ortiz there. “The first time I met Virgil, he was 6 years old. He was making little pottery pieces—little animals and then a couple of years later, his animals became more unusual. They became like small little dinosaurs,” he said. Even at this young age, Gallegos said Ortiz was “thinking outside of the box.”

Ortiz remembers meeting Gallegos. “He asked my parents, ‘Who’s teaching this kid how to do these really different figures?’” Gallegos asked because he had seen something like them in his own collection. He invited Ortiz and his family to visit the collector’s showroom, which had one the largest collection of these pieces from the 1800s. “We flipped out,” said Ortiz. “We walked in and looked up on his shelves and everything that I had been experimenting on were almost exact replicas of what he had.”

“My parents yanked me out of the showroom. They took me outside and they just said, ‘Remember this day because this is something that we didn’t teach you. We didn’t even know these pieces existed,’ ” Ortiz said. “It’s ancestral memory. There’s no other explanation for it.”

The visit changed Ortiz’s view of his art, and inspired him to continue on his journey. “Growing up, I was making storytellers. I was making traditional pots with various elements painted under family designs,” Ortiz said. But then he began to experiment. “My style changed from what I was taught. I was making static pieces that were standing up, and I was painting them like with a fashion sense or just different characters.”

Rather than seeking a higher education, Ortiz said he wished to walk in the shoes of his Cochiti ancestors by creating artwork that reflected the world around him. He drew upon his view of encroaching big city life that he saw in places such as New York, creating comical, and sometimes shocking, figures such as performers or prostitutes.

When Ortiz reached 18, Gallegos asked him to make figures that personally inspired him. One of these was based on a transgender character in the film “The Crying Game” that was two-sided: one side had a male face with female genitalia and the reverse was on the other side. He also made a figure of a Lady of Guadalupe (Virgin Mary) that had a zipper on the middle of the body. Gallegos said when he asked Ortiz “‘What’s the zipper for?’ He said, ‘We are Catholic by day and Indian by night.’ I said, ‘Wow, that’s beautiful.’”

Gallegos said that in the same way the Cochiti artisans of generations ago might create sculptures of clowns or bearded ladies seen at traveling carnivals, Ortiz is telling the world what he sees as a Cochiti artisan in the 21st century. “A hundred years ago, they didn’t have the voice that they have today. They had to be a little more cautious in how they criticized or made fun of the outside world. But today, Virgil can tell his story and be very direct,” said Gallegos. “When he tells a story, he doesn’t necessarily criticize anybody, he just tells it like it is.”

Ortiz noted an important bit of Pueblo history in that his ancestors were the ones who worked to build the churches of the encroachers. Due to the influence of religious beliefs and church leaders that accused the Cochiti people of witchcraft and sorcery, Ortiz says it’s been a fight to reclaim what was lost so long ago.

“All the Pueblo people built the churches and now we all have churches on the Pueblos. They had to try to sap out all the artwork, all of our ceremonies, or everything about us and our language. And we fought back. So finally, that’s how the Pueblo Revolt took off . . . it pulled tight everybody together. It’s America’s first revolution, it’s called that because of the genocide that happened. Most people do not have any idea of all of our histories because it’s been stamped out.”

An Otherworldly Perspective

In the four decades since he first began to explore his art, Ortiz has expressed himself through many forms, from fashion and costumes to photography and graphic design. He has also combined traditional designs and materials with stories from the future, inspired by when he first saw the original “Star Wars” movie as a child in 1977. He was fascinated by the movie and its characters. “I remembered every single detail. Where they came from, how their ships looked or what they wore, how they spoke,” he said.

The science fiction genre has continued to fuel his imagination. In 2008, he started writing a storyline called “Revolt 1680/2180,” which he has portrayed through a series of works, including jars, busts and now live actors portraying different characters in the story. Together, they depict a dystopian future 500 years after the Pueblo Revolt in which time travelers return to the era of the revolt to aid and record the culture of their ancestors. This epic tale has culminated with the release this year of eight “Recon Watchmen” in full costumes and masks that were fitted for the actors who are portraying them. These Watchmen have joined other characters in the story to protect the Pueblos of the past, preserving and recording traditions so they can survive and be passed on.

Ortiz even has been working on a screenplay to tell the story. “I developed 19 groups of characters that represent the 19 Pueblos that are still left in New Mexico today. Characters like the Watchmen would represent one Pueblo—the Blind Archers, the Translator Army, the Venutian Soldiers, all of these different characters are assigned to the 19 Pueblos.” Ortiz said the project is a way of “telling our future, mixing that with our present day and then also our historic times, and tying them all together.”

Ortiz has exhibited some of the pieces before, as in 2018 at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Center titled “Revolution: Rise Against the Invasion.” However, now he will tell the whole story in four parts at four different venues in Santa Fe, New Mexico, beginning with the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, New Mexico History Museum and Santa Fe Indian Market in August, continuing on to Meow Wolf art venue in September and then in one of the inaugural exhibitions at the the New Mexico Museum of Art Vladem Contemporary in 2023.

Merry Scully, head of Curatorial Affairs and curator of Contemporary Art at the New Mexico Museum of Art, said Ortiz was one of the first artists she considered for this inaugural show at the museum because “his is a work that is so grounded in the history of this location. It is so important and crosses so many boundaries.” The title of his installation in the “Shadow and Light” exhibition at the new museum will be “Leviathan: Plight of the Recon Watchmen.” She explained that the title plays off the landscape. “It’s this idea of artists being drawn here by the light of New Mexico, but also it suggests moral conflict, big issues and cultural tensions,” she said. “These are aspects of his works.”

Scully also said that Ortiz’s work fits well with her museum’s intent to show art that is contemporary as well as tied to tradition and location. “It has its own kind of identity. I find really interesting connections to it from all kinds of places, like manga [Japanese comics] or speculative fiction,” she said. “He certainly is respecting yet pushing tradition.”

Inspiring Future Generations

Ortiz’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris. This year, he received the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture’s Living Treasure Award and published a mid-career retrospective of his works entitled “Virgil Ortiz: ReVOlution.”

Looking back at the beginning of Ortiz’s career, his sister Mary Ortiz remembers when she returned home from college and first saw that her brother had started making figures in the ways of their Cochiti ancestors. “This all came from his imagination. It was really cool because of that connection back to the past,” Mary Ortiz said. “He was encouraging us to start doing standing figures, so basically we started doing that.”

In recent years, Mary’s two daughters have also become pottery makers, and now one of her granddaughters have become interested in creating with clay. She said given that the pottery making of her ancestors was once stopped, seeing this live on is encouraging: “I just would like it to continue, for the younger ones to get involved, for it to pass on from generation to generation.”

Ortiz is also glad his family tradition is thriving. He hopes his legacy will be that he helped perpetuate the pottery making traditions and culture of his Cochiti people and that others will be aware of their history. “I won’t ever feel successful until I leave this realm and the pottery tradition stays alive and the world knows about the Pueblo Revolt.” He also wants to inspire other Indigenous artists. He said he wants “to be able to lift them up, help them continue on their dream, and let them know everything is possible.”

The Recon Watchmen

During the 1600s, the Spanish had colonized parts of the Southwest. In 1680, a Pueblo leader named Po’pay led a successful revolt against them, pushing them out of the Pueblos they had begun to occupy.

“Po’pay Onyx,” Revolution Series, 2021; high-fire clay and glazes; 19.5” x 12” x 17”. Photo Courtesy of Virgil Ortiz

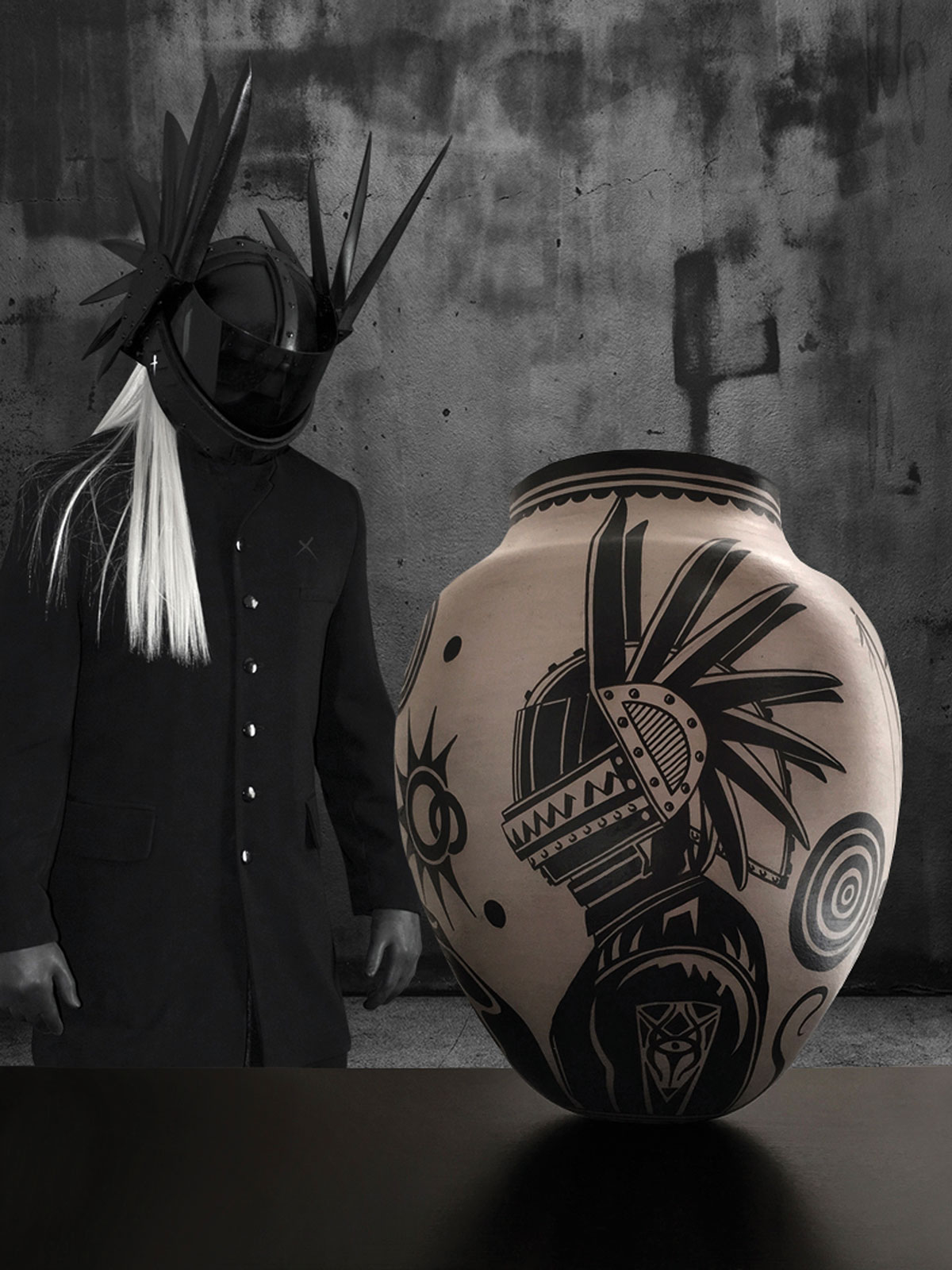

Ortiz’s “Recon Watchmen” from the year 2180 are watching over the past, present and future of the Pueblo peoples in New Mexico. During the past two decades, Ortiz has been creating a combination of ceramic pots and busts as well as masks and costumes that depict 19 groups of characters representing the 19 Pueblos in New Mexico. One group is the “Aeronauts,” depicted here in full costume and on a traditionally made Cochiti pot.

“Aeronaut” character in costume and on vessel, 2018; Cochiti red clay, white clay slip, black pigment (wild spinach); 18” x 14”. Photo Courtesy of Virgil Ortiz

This past year, Ortiz has made full costumes and masks of his Watchmen characters in anticipation of filming his screenplay “Revolt 1680/2180.” Ortiz said, “It is not just a story of persecution and revolt but also a story of resilience.” The Watchmen—led by their matriarch dressed all in white—conduct covert surveillance of Earth to detect any movements of a Castilian army toward the Pueblo lands. In this scene, they have driven out the invaders and have recovered artifacts (the ceramic busts) from the battlefield.

“Recon Watchmen” donning masks, helmets adorned with Stargate crests and Ha’pons (war shields), which have LED lights that can glow. The characters stand with three ceramic busts from the series. Photo by Kamden Storm

In Ortiz’s story, the Recon Watchmen aid the Puebloans in rebuilding their traditional life on new sacred ground that the invaders once destroyed. These and the other ceramic busts of the Watchmen have been excavated from our future and their past. The beads on their heads represent microchips that have recorded the culture, language and traditions of the Pueblo people, including pottery-making techniques.

“The rebellion remains a significant part of New Mexico Pueblo history, and I have always felt it my duty to cultivate and share it with the world,” Ortiz said. “It is important to pay respect to the past to advance into the future.”

“Corvis” (foreground) and “Grus,” Recon Watchmen series, 2021. High-fire clay, glazes and glass beads; Left: 14” x 8” x 11”, Right: 14” x 8” x 12”. Made in collaboration with bead artist Elias Not Afraid (Apsáalooke). Photo by Kamden Storm

Each Watchman has a mask made of latex, silicone and resin that is custom-fitted to the model’s face and painted with design accents. Their weapons are crafted from wood and metal, Their attire is made from silk fabric and bear Ortiz’s signature designs.

“Ceeyon” and “Shutah,” Recon Watchmen series, 2022. Photo by Isaiah Vigil