Textiles are intimate objects. “They are always with you. From the moment you are born, you are wrapped in a fabric until the moment you leave this world and you are wrapped in another,” said Hector Manuel Meneses Lozano, director of the Museo Textil de Oaxaca (Textile Museum of Oaxaca) in Mexico. Whether it is the rug we step on as we get out of bed or what we chose to wear, these seemingly discreet choices of items, he said, “speak volumes as to who you are.”

Even a scrap of fabric can be a time capsule—a record of the history and culture of an individual, a family or an entire community. Clothing can mark a transition such as a birth, passage into adulthood, marriage or death. It can reflect achieving a particular rank or tell of having fought in battle. A single shell or glass bead can indicate trade between peoples hundreds of miles apart.

Conserving such objects and connecting them with the communities from which they came is essential to the National Museum of the American Indian. From 1999 to 2004, as the museum was preparing to exhibit 4,000 items in its new museum in Washington, D.C., it was also relocating its some 800,000 collection items from the museum’s original storage facility in the Bronx, New York, to its new Cultural Resources Center in Maryland. Among these items were thousands of textiles. Staff had only one year to inventory the complete collection before the move. “Everything had to be done so fast,” said Susan Heald, NMAI’s head of textile conservation.

Heald managed to design a flexible housing system for the new Cultural Resources Center that could accommodate existing and potentially future textiles. However, after 15 years of intensive visitation and collection use, the housings had become worn and some items disorganized. So when the opportunity came to evaluate and address the individual storage needs of the collection’s large textiles, this was a monumental project the museum was glad to take on. With multiple grants from the Smithsonian’s National Collections Program Collections Care and Preservation Fund, by the end of 2022 the museum will have upgraded the “housing” of more than 6,000 textiles.

Complex Challenges

The idea for the project was sparked in 2015 when NMAI Conservator Elizabeth Holford and Museum Specialist Veronica Quiguango were attending to the collection. Quiguango is from a long line of Kichwa weavers in Ecuador and said caring for textiles is a “personal connection to my roots.” On constant vigil, they vacuumed each drawer to remove any dust or stray particles. While doing so, they began to note simple yet effective actions that could be done to help conserve the objects.

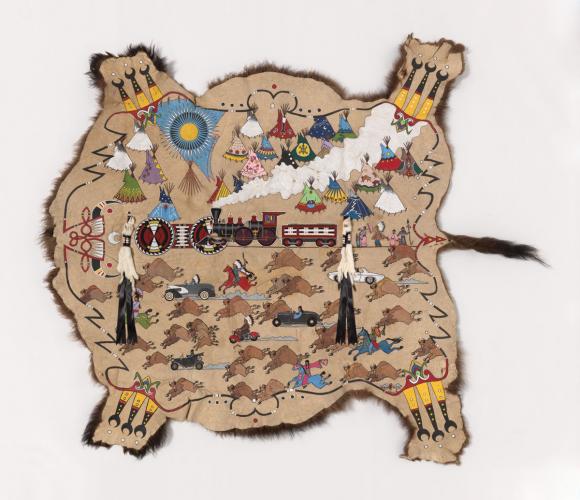

The items in the collection that were targeted for the project were anything with a “flop factor,” explained Heald. “That which has been woven, twined, knitted, knotted and felted textiles as well as clothing and large, flat flexible items made from fur, feathers, skin, bark, reed and rush.”

Addressing the needs of such a range of objects, however, is not easy. As NMAI’s Head of Conservation Kelly McHugh said, “textiles are complex.” They are often made with multiple materials, each of which has individual needs. Metal can oxidize and corrode. Feathers can’t be handled frequently or washed or their natural oils begin to break down and they become more fragile. Animal skins can also dry and then shrink, causing “fur slippage,” meaning the fur will begin to fall off the skin.

The collection team put together a plan, including calculating about how much attention, and therefore time, each object might need. The collection at the Cultural Resources Center is organized by region and then by culture. In 2017, they began with textiles from the Arctic, worked down through those from North and Central America, and as of 2019, made their way to those from South America. This last phase of the project includes textiles found during archaeological excavations, many of which are thousands of years old.

Customized Accommodations

The Cultural Resources Center is kept at a constant humidity and temperature to help preserve the items. However, many are made of natural materials such as cotton, wool and fur, and “organic materials by nature just want to deteriorate,” said Holford. “We are fighting an ongoing battle we are never going to win. The best we can do is slow down the process and make them as comfortable as possible.” Yet the museum doesn’t take an invasive approach. Holford said, “The most passive way of conserving these objects is to create housing systems that are more sympathetic to the items and good handling protocols.”

Contract conservators Nora Frankel and Hannah Muchnick joined the project in 2019 and have taken on much of the hands-on rehousing work. They employed a housing system NMAI collection team members developed in which every screened drawer would be lined with a white, corrugated polypropylene board. Then they created a tray with walls out of Tyvek, a polyethylene material, fitted around each garment or other textiles to capture any small fragments of threads, feathers or fur or objects such as beads that might fall from cultural items over time. A layer of acid-free, sulfur-free cotton tissue paper was sometimes laid underneath very fragile garments and painted textiles for added protection. The team also developed a folding technique for garments that would allow visitors to see important details without unfolding the garment completely yet take up less room in the tray, enabling more items to be stored per drawer.

Some items need special attention. For example, some pieces of fabric had tags still stapled to them that had to be carefully removed and replaced with a sewn tag to keep them from being marred by corroding metal. Also on the agenda is to humidify and flatten bark cloth and other items made from plant fibers that were folded and distorted.

Many large mats, robes, rugs and tapestries were rolled, which can help prevent them from unraveling or tearing as well as save space. Exceptions include those that were exceedingly fragile or hundreds of years old which were best laid flat. One of these was a potentially 500-year-old, finely woven Inka tapestry recovered from a cave near Lake Titicaca known as the “Temple of the Sun.” Covered in iconic animal and other figures—including a mermaid—the incredibly preserved textile looks as though it was made just a few years ago. As it is a frequently viewed item, rather than having it rolled and unrolled to view the stunning scene of creatures, it will lay flat. “This represents deep history,” commented McHugh. “The complexity of the weave is incredible, and the techniques go way back in time.”

Very large, elaborately decorated items, such as painted robes made from buffalo hide, were also best stored laid out—which means in some cases having shelving to accommodate items that are several feet in diameter. “We learned how to play the Tetris game of collection storage,” Holford said.

Whether a tapestry, a ceremonial dress or an everyday garment, each textile is personal—something the conservators recognize and appreciate. Frankel, a former NMAI Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in conservation, is also a multimedia artist who works in fabric. She said she tends to come at conservation from the maker’s perspective and can often visualize the person who made it from the shape of the clothing or the choice of material. “It is a way to connect to someone through time and space,” she said. For example, “a lining of a vest or jacket, that is just for you. No one else sees it—and people tend to pick bold choices. That tickles me a little bit.”

On a day at the Cultural Resources Center this past May, Muchnick was building a tray to house a Bolivian Ch’uta dance outfit, including a boy’s jacket and pants. As she assessed them, she remarked that the young man must have been about her size. “You get a real sense who wore these garments,” she said. In examining a Shawnee jacket, for instance, she found bits of dried flowers in a pocket, long forgotten by who picked them.

During the rehousing process, every object has been photographed, its information entered into a database and then given its own barcode label secured to its tray. In the case of the rolled rugs and tapestries, each has a photo of the entire item affixed to it on the outside so anyone wanting to see it wouldn’t necessarily have to unroll it, reducing the times it is handled.

Once a textile is prepared and its new housing is complete, where it is stored is just as important. Many Indigenous cultures consider certain objects to be living once created. Some need to see light whereas certain ceremonial or otherwise sacred items that are not to be viewed except by particular people are stored high. A group of Navajo rug weavers came through the center and advised that as many of their weavers are now elders, they needed the rugs placed lower in the stacks to reach them. “This kind of input from the community is so valuable,” said Heald. As the reorganization has optimized storage space, the center has room for any such adjustments as well as for additional items that might come through the door.

Welcoming Communities

The rehousing project will most certainly prolong the life of these textiles in the museum’s care, proving the adage that “a stitch in time, saves nine.” Ultimately, however, the goal of rehousing of these textiles is to increase access to the collection for all the Indigenous communities it represents. During the first phase of the project, in 2018, caribou skin sewers from Nunavut, Canada, visited the Cultural Resources Center and commented about the respect given to their family’s items there. “It makes a difference in how we handle the collection,” McHugh said, “to prevent damage but also as a signifier to our constituency that we are taking time and care for their belongings here.”

Yet not everyone can make the journey to the Cultural Research Center. While the COVID-19 pandemic cut off access to the collection temporarily, it also eventually spurred more access for community members in other countries through virtual consultations. This past spring, NMAI hosted a virtual consult for Dill Yel Nbán, a collective of Yalaltec researchers and others who promote the Zapotec language and culture of the northern mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico. Meneses Lozano, who has been collaborating with the collective on an exhibition to be featured at his museum, joined them on the virtual consultation, which was conducted in English and Spanish. During the meeting, NMAI staff at the museum in New York opened up and climbed into one of the glass cases in the “Infinity of Nations” exhibition to show them an outfit on display. Then staff at the Cultural Resources Center in Maryland zoomed in on the complex embroidery on some delicate cotton "huipils" (blouses), "rebozos" (shawls) and wrap-around skirts. During the session, one of the researchers in Mexico, linguist Ana Alonso Ortiz, exclaimed in Spanish, “The details are so particular. They are very beautiful.”

Recalling the consultation, Meneses Lozano said, “As someone from museums, I was impressed how far museums could go to offer access to items that we care about. Because most of the time museums hold them in storage in areas where it is very difficult to look at them. Or if they are on display, it is hard to see details behind glass. They really outdid themselves.”

During virtual consultations, community members will be able to take photographs and can receive a recording of the session for their records. Local museums also can see items they might consider for loans while NMAI can learn more about the objects’ identity, use or history from community members.

To further the museum collection’s reach into Indigenous communities, Kichwa intern Sammia Quisintuña Chango from Salasaca, Ecuador, recently joined the team. As a fluent speaker of Kichwa, she initially will be reaching out to weavers from Mexico and Ecuador to invite them to engage with their cultural items virtually and develop a shared stewardship of the collection.

As Quiguango translated for her, Quisintuña Chango explained that as she comes from a family of textile makers. She said, “it is in my blood to do this.” Wearing a blouse she embroidered herself with green, purple and blue thread representing animals, plants and water in her country, she said the clothes Indigenous weavers make “reflect the identities of their communities.”

Quiguango agreed, saying, “Every object has a story. It is a matter of finding the community members to unravel that story.”

Quisintuña Chango said she is looking forward to connecting the vast NMAI collection to Indigenous communities. In addition to proper care, many items need to be visited to thrive. “They are our ancestors and they are alive,” she said. Reuniting with them helps “heal us as individuals and as a community.”