For more than 50 years, the work of Saulteaux Anishinaabe artist, curator and writer Robert Houle has united Indigenous cultural heritage and design with Western contemporary art practices to examine spirituality, history, cultural appropriation and the ongoing fight for Indigenous sovereignty. He calls the result “transcultural”—a synthesis of Indigenous and Euro-American ways of making and thinking about art.

The first major retrospective exhibition of his work, “Robert Houle: Red Is Beautiful,” opens May 25 at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. Curated by Wanda Nanibush (Anishinaabe, Beausoleil First Nation), curator of Indigenous art at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, “Red Is Beautiful” honors not only the breadth of Houle’s oeuvre but also his singular method of processing trauma and resilience through artistic expression.

Liberating Cultural Heritage

Born in 1947, Robert Houle grew up within the Sandy Bay First Nation in Manitoba. Though he was raised learning the Anishinaabe language and cultural practices of his extended family, his experiences of physical and emotional abuse at his community’s Catholic mission-run residential school—part of the Canadian government’s attempt to assimilate Indigenous people—left deep wounds.

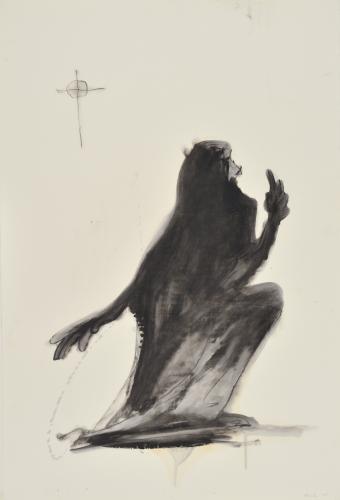

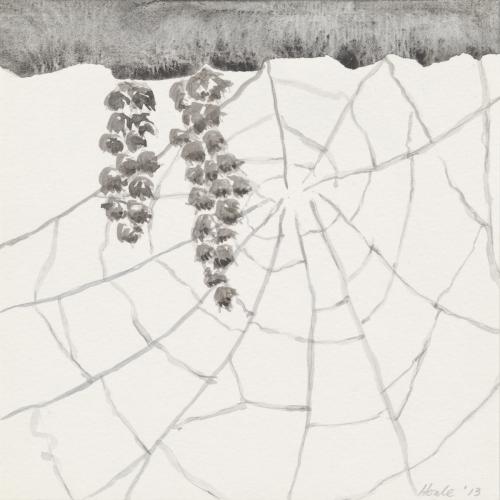

Decades later, he would process his trauma through works such as “Sandy Bay,” which recounts and records Houle’s memories as a way to heal, as well as the black-and-white depictions of his nightmares, seen in “Sister Clothilde,” and their antidotes, dream shamans. In these works that address the past and healing, Robert identifies with “pahgedenaun,” a Saulteaux term he learned from his father meaning “to let [it] go” from one’s mind. “Beauty is a way of tempering a narrative that could be a victimizing narrative,” reflected curator Nanibush on the power of “Sandy Bay.” She said, “It can fill that narrative with hope, it can fill that narrative with empowerment.”

Houle was introduced to art during high school, after which he achieved concurrent art history and art teaching degrees in the early to mid-1970s. During his art history research, he was drawn to the abstract expressionists, particularly the vibrant color works of Barnett Newman. He was further inspired by contemporary Native artists’ uniquely Indigenous approaches, which were rarely displayed in museums and galleries at the time.

In 1977, the National Museum of Man (now the Canadian Museum of History) hired Houle as its first curator of Contemporary Indian Art. Groundbreaking as his role was, Houle recognized that his colleagues remained driven by the same mindset that has characterized the museum field since the 19th century—the erroneous belief that Indigenous people were dying out and museums existed to salvage their remaining cultures. Native contemporary art remained relegated to ethnographic collections rather than being considered fine art created by living people.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Houle witnessed an Indigenous cultural renaissance concurrent with growing political activism. His position afforded him the opportunity to meet contemporary Indigenous artists such as painter Norval Morrisseau (Anishinaabe), who became both an inspiration and a close friend. This cultural resurgence occurred in stark contrast to how Houle saw some museums treating Indigenous cultural heritage items. It was the museum’s dissection of a medicine bundle left under its protection that finally triggered Houle’s resignation after three years in his position there. He then resolved to “liberate” the heritage items he left behind. “How do I do that?” he recalled in a conversation in the Autumn 1988 issue of Muse. “I am leaving. What can I do to breathe life into them, to show that they still matter?,” he said. “Up until last year I concentrated on making parfleches [pouches] and warrior staffs, trying to rehabilitate those objects I left behind.”

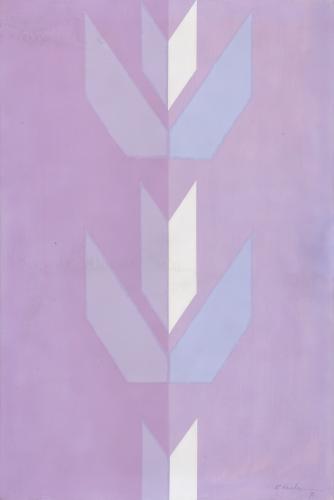

Since that time, Robert Houle has continued to “rehabilitate” museum collections on his own terms: in a blend of what he calls the “spiritual legacy of the ancient ones”—the rich artistic heritage of his ancestors—and Western abstraction. Early works such as his 1972 “Ojibway Motif, #2, Purple Leaves Series” interpreted ancestral beadwork designs into modernist, geometric forms. “Red Is Beautiful,” the first painting Houle sold to a museum, was inspired by patterns on woven bags. “His innovation is that he’s thinking of [traditional Indigenous designs] at the same time he’s thinking of the history of abstraction from a Western point of view,” asserted Nanibush. “He brings that together as something new.”

The Power of Color and Form

As a colorist, his intense palette is representative of his abstract approach yet is infused with meaning derived from his Indigenous identity. “Especially within an Anishinaabe point of view, color has spiritual capacity and it has emotional capacity,” Nanibush observed. Houle uses color to express gender, emotion and memory while resetting imbalances. “Sometimes the color seems to be to me an interaction with the Western tradition. So he’ll throw pink in where … the field might have been uber masculinist. It’s almost like he’s inserting a kind of feminine energy there or at least a criticism of the over-masculinist traditions within Western abstraction.”

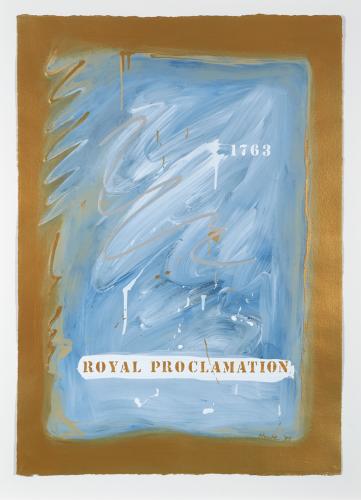

Some of his earliest work while still a student at McGill University evidences his experimentation with color and emotion. Asked in 1972 by a professor to paint love, he drew inspiration from love poems a friend wrote to create a series of pastel, geometric paintings. His 1999 “Palisade I” combines historical significance with cultural symbolism: the vertical green canvases represent the palisades surrounding the British forts captured by Great Lakes First Nations during Pontiac’s War; the color also signifies the green wampum belts used to convey diplomatic messages.

His admiration for the color-field abstractions of Newman and innovation of Morrisseau in part allowed Houle to follow this syncretic path. “Newman was so huge because he could combine spirituality and abstraction,” said Nanibush. “With Morrisseau it’s more about him being Anishinaabe, it’s more about him taking his own people and the art community and doing something on his own, so it’s a different type of permission. It’s permission to talk about our culture in contemporary art and believe that it’s relevant.”

Similarly, Houle’s works based on the parfleche, an envelope often made of rawhide and customarily painted with geometric designs, are dedicated to contemporary Indigenous artists or delve into Houle’s exploration of spirituality. Both his Catholic and Anishinaabe religious upbringing significantly influenced his art and identity. For example, using paint and porcupine quills on paper for his 1983 “Parfleches for the Last Supper,“ Houle rendered Jesus and his apostles into parfleche form.

Taking a Stand

During the 1980s, Houle’s work increasingly critiqued colonial interpretations of history, the appropriation of Indigenous names for commercial purposes and Indigenous peoples’ resistance to continued government encroachment on their land and autonomy. In 1989, First Nations protestors blocked a logging road at the Canadian town of Temagami to challenge logging on tribal lands. In 1995 at Ipperwash, a community on Georgian Bay in Ontario, a First Nations demonstrator was shot to death during a confrontation with provincial police over the government’s occupation of tribal lands. In 1990, the Mohawk community of Kanehsatà:ke protested the expansion of a golf course into First Nations lands. Houle’s large-scale paintings dedicated to these acts of resistance stand to inform the public about First Nations’ experiences of injustice.

The quincentenary of Columbus’s landing in North America, 1992, was cause for many Indigenous artists to publicly rethink colonialism. During that year, Houle co-curated the influential exhibition “Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations” at the National Gallery of Canada. This was the first major exhibition of Indigenous contemporary art from Canada and the United States and placed both contemporary Indigenous art and land’s spiritual and political legacy at the fore.

That same year Houle completed “Kanata,” a monumental work that borrows British-American artist Benjamin West’s 1770 painting “The Death of General Wolfe” to reframe Indigenous peoples’ role in Canada’s founding. He removed the painting’s color except for the adornments on the single Native person in the image and inserted symbolic elements missing from the historical record such as a figure of an Indigenous woman and a Native person canoeing away.

Houle has continued to represent Indigenous experiences in his work, not just as a response to the dominant interpretation but also from a particularly Indigenous point of view. Throughout his lifetime of work, whether through elemental geometric works based on his cultural heritage or processing personal and community history, he adheres to traditional concepts of spirituality and beauty in his art that continue to provoke and inspire our emotions. “My art gives me a lot of strength to critique something, and I knew I had to do that,” Houle commented. “It’s been a way for me to deal with my own personal issues about our country and about our politics and about the way women are treated.”