When Hopi pottery maker Karen Charley visited the Smithsonian Institution in 2019, she knew that she would be inspired by the workmanship and designs of the pottery made by her community’s ancestors in its collections. She didn’t, however, anticipate finding a bowl from her own grandmother.

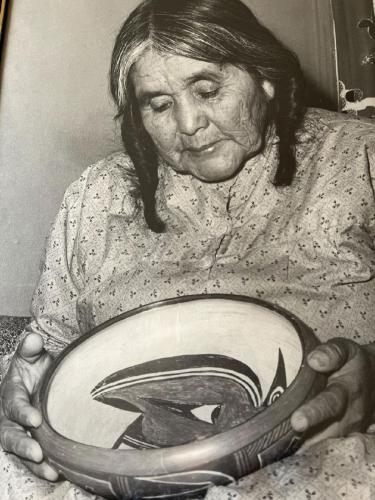

A member of the Hopi Butterfly Clan, Charley learned her pottery making skills from her mother, Marcella Kahe, and by observing her grandmother, Qötsa Mana. Charley recognized her grandmother’s shallow bowl in the collection at NMAI’s Cultural Resources Center by its polychrome design—multicolored sections on white slip. Some of the black or white, round shapes on the bowl may be clouds, common motifs on such pottery as the Hopi people live in an arid climate and hope for rain, Charley explained. She has incorporated similar polychrome designs into the two-handled canteens and other pottery she creates. “We put prayers into them,” she said. “These come out in our designs.”

Charley and the seven other Hopi pottery makers with her were able to visit the National Museum of the American Indian and National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., through the museums’ Recovering Voices program. This initiative provides resources for Indigenous community members to travel to the Smithsonian museums and “supports their efforts to conserve cultural knowledge,” said Recovering Voices Director Gwyneira Isaac. She and Lea McChesney, the curator of ethnology for the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology at University of New Mexico, worked together to bring the Hopi pottery makers to the Smithsonian. McChesney said, “To see how the Hopi potters work, how close they are with the materials, the care that they take along the way—it is so impressive.”

Charley said when she looks at all the tools in her workshop, she worries that the knowledge they hold—even their Hopi names—will be lost if she doesn’t pass it on. Part of her goal in visiting the Smithsonian’s collection was to bring back what she learned to youth in her community, including her own granddaughter. Charley said when she visited the pottery in the Smithsonian, she was energized. “They are so happy to see us,” she said. “I used to feel sad about leaving them, knowing that they were moved from our communities and that they live somewhere else. Now I’m glad these are where they are because they are well taken care of, and if they weren’t there, they might have been lost. It is good for our younger generations to see them.”