First, you enter a world in darkness. Then moving into a dim room, you hear and see rain falling behind a canoe. Across from this is an all-white raven. At the center of the room, you see the bird’s remarkable transformation into a human boy. You will next enter a Tlingit clan chief’s house that has a great bounty of precious objects, including intricately carved glass boxes that glow.

This is just part of the multisensory exhibition “Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight,” which is scheduled to open January 28, 2022, at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. Raven is a prominent figure throughout North Pacific Coast cultures, including in many creation stories. In “Raven and the Box of Daylight,” this trickster is reborn as a human child who manipulates his grandfather, a clan chief, into giving him coveted boxes full of the stars, moon and sun. Releasing them, he brings light to the world.

While many versions of this tale are told, it has never been presented this way before. The exhibition features more than 60 glass objects and sculptures created by international Tlingit artist Preston Kochéin Singletary. Visitors will be guided through Raven’s story by stunning glass pieces paired with projected light, moving imagery and ethereal soundscapes.

The immersive exhibition began as a collaboration between Singletary and the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington. More than three years in the making, when the exhibition first opened in 2018, Rebecca Engelhardt, the exhibitions and collections manager at the museum, said visitors were “gobsmacked by the experience.” This innovative show is not only the artist’s magnum opus but reflects the way in which he has transformed how people view traditional Tlingit art.

A Long and Winding Road

As a youth growing up in Seattle, Washington, Singletary didn’t plan on being an artist. Rather he thought he would be making a living playing guitar in a rock band. But in 1979, at the age of 15, he met Dante Marioni, the son of famous glass artist Paul Marioni. In 1982, Dante helped Singletary get a job at the The Glass Eye Studio in Seattle, where he would be trained in making objects such as vases.

In 1984, he attended his first of many glassmaking workshops at the Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington. His time at Pilchuck would help propel his interest in the glass arts as well as his heritage. He met Isleta Pueblo sculptor Anthony Jojola and Tlingit wood and neon artist David Svenson, both of whom encouraged him to learn more about his Tlingit ancestry and express it through his art.

During the next two decades, he attended workshops at Pilchuck, where he trained with Italian masters such as Checco Ongaro, Pino Signoretto and Lino Tagliapietra as well as American artists Dan Daily and Richard Royal. He also worked at leading glassmaker Benjamin Moore’s studio. In 1993, he traveled to Europe and Japan to observe master glassmakers and then made his way to a design school in Scandinavia. There he courted Åsa Sandlund, a designer who would become his future wife, and worked as a craftsman in residence for six months. He created vessels that reflected the clean Scandinavian style while working on perfecting his Tlingit designs. “I was straddling two different worlds,” he said.

Back in Seattle, Singletary became a distinctive part of the Washington glass studio art scene. He learned and found inspiration from scholars and other Native artists, including Steven Brown, Duane Pasco, Joe David (Nuu-chah-nulth), Ed Archie NoiseCat (Salish), Marvin Oliver (Isleta Pueblo/Quinault) and Shdal’éiw Walter Porter (Tlingit).

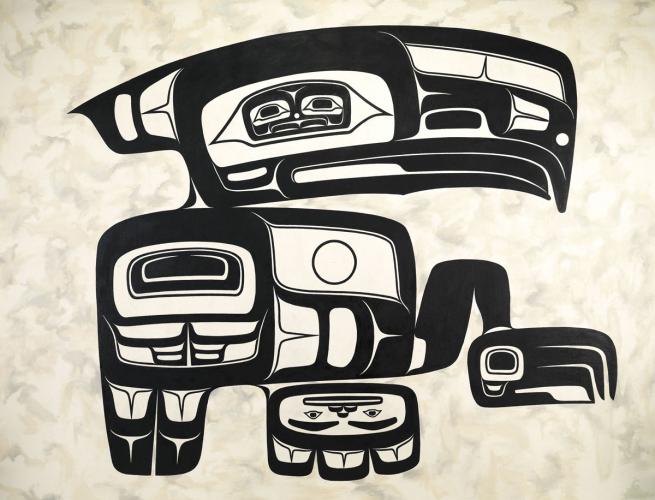

Singletary’s works often feature themes of transformation as well as the iconic animal and human figures, objects or ovoid shapes and faces characteristic of North Pacific Coast art and formline design. Yet some may view such art as not truly Tlingit because his pieces are made from glass rather than wood or other traditional mediums. Singletary disregards such thinking. Native people are “early adopters of every kind of technology,” he says. He and his team are “transforming the culture and forging new paths. And that should be allowed.”

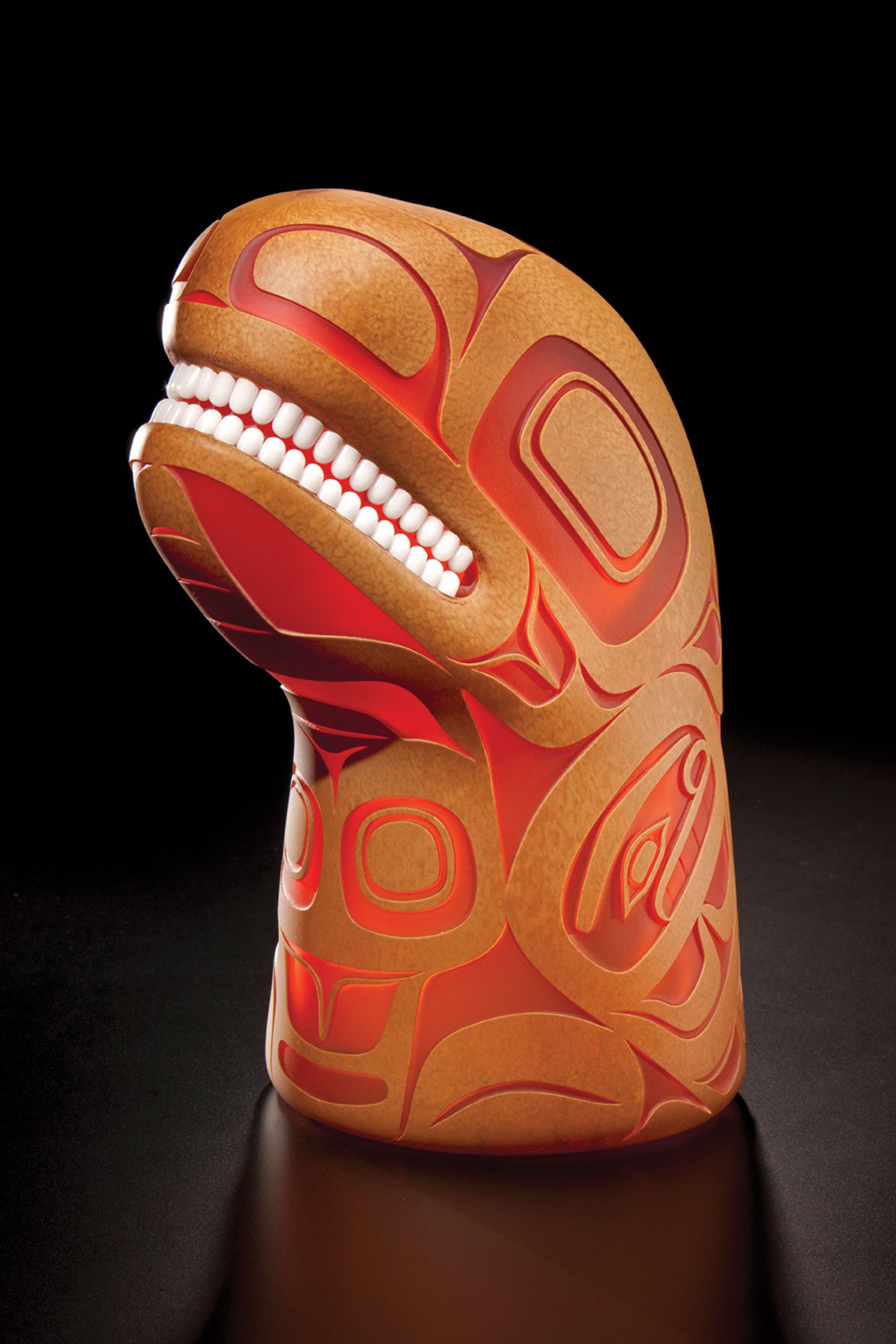

NMAI Curator and Ogala Lakota artist Emil Her Many Horses was impressed by Singletary’s innovative use of glass when he first saw his works at the Santa Fe Indian Market a couple of decades ago. When NMAI was preparing for its opening in Washington, D.C., in 2004, Her Many Horses commissioned Singletary to make a large raven head holding a sun in its beak for one of its inaugural exhibitions, “Our Universes.” (This artwork would later inspire Singletary to create a similar piece for the “Raven and the Box of Daylight” exhibition.) In 2011, NMAI in New York would go on to host Singletary’s “Echoes, Fire and Shadows” exhibition that was also originally created for the Museum of Glass. This mid-career survey featured a great range of Singletary’s works, from glass vases and large figures to an object close to his heart, a Martin guitar painted with his formline designs.

When Her Many Horses saw Singletary’s “Raven and the Box of Daylight” at the Museum of Glass, he was floored by the sheer number of pieces the artist had produced for the solo show as well as their quality and knew he wanted the exhibition at NMAI. “Preston has perfected his art and his designs,” he said.

His pieces are now showcased in museums around the country. He has also received many awards and recognitions, including the Rakow Commission from the Corning Museum of Glass and an honorary doctorate of arts from the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. “It has been a pleasure to work multiple years with Preston and watch him grow as an artist.” says Engelhardt. “He continues to build upon an amazing body of work.”

Singletary—who says he is “a musician trapped in a glassblower’s body”—also feeds his hunger for music by playing bass guitar in his funk rock band, Khu.éex.’ The band, whose members are Tlingit, Haida and Blackfoot, tells stories and sings songs about Indigenous issues in Native languages.

A Collaborative Art

Unlike many other artforms that are created by individuals, “glassblowing is kind of a team effort,” says Singletary. This is particularly true for his glass pieces that are several feet tall and can weigh hundreds of pounds.

The process of creating glass works depends much on their size, but they all start with designs he has drawn. For smaller pieces, colored glass at the end of a steel pipe is melted in a furnace that can reach temperatures up to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit until it reaches a liquid state. Colored powders are sprinkled on top in layers as the pipe is continually rotated, then taken in and out of the furnace, blown into and rolled again so the piece keeps its desired shape. When the piece is ready, the artist’s assistant will take a bit of melted glass and as the glass blower stops rotating the piece, adds this “punty” of glass to the piece’s end. At precisely the right moment, the pipe is tapped and the piece breaks away, leaving the piece attached to the punty. The artist will keep the piece malleable and shape it in the furnace’s “glory hole” until it is ready to be separated from its punty base. It will eventually be transferred to an “annealing oven,” where it cools for hours, or in the case of some larger pieces, days.

Singletary carves the designs on his pieces by using a high-pressure sand-blasting tool that removes layers of colors. He draws his design on a portion of thick green rubber that he lays over the piece to guide the tool and protect what he doesn’t want to cut away. This reductive process is repeated until he completes the design on the work.

Large sculptures and other pieces may be shaped by pouring molten glass into a mold that is designed by the artist and then polished. To make these, Singletary works with glassmakers in the Czech Republic, where kilns of immense size are available.

Throughout the process, he has the help of assistants, many of whom work with him in his Seattle studio. He also leads glassmaking demonstrations at the Museum of Glass’s hot shop, where he has collaborated with several other well-known glass artists. Engelhardt says of Singletary, “He is an incredible artist to work with. He brings great people to the table.” Singletary says he enjoys helping other artists “realize their own ideas in glass. It challenges me.”

Reshaping a Classic Story

To create “Raven and the Box of Daylight,” Singletary truly needed a large cast of talent. First, he and guest curator Miranda Shkík Belarde-Lewis (Zuni/Tlingit) looked at five different versions of the Raven story as told by four Tlingit storytellers. A group of Tlingit speakers translated the original tales. One of the stories was from Tlingit mythologist Walter Porter, who Singletary initially asked to curate the exhibition. However, Porter died in 2013 before they could begin to work on the project. So Singletary asked Belarde-Lewis, a former NMAI curatorial research assistant who is now an independent curator and assistant professor of North American Indigenous Knowledge at the University of Washington, to take on the task.

Singletary also enlisted visual artist Juniper Shuey to design the moving imagery and direct the lighting of Singletary’s creations. “The space and the environment influence how you view the objects,” he says. For example, in the room that is the clan chief’s house, light seems to pour out of the ceiling onto the grey and black “transformation hat,” projecting its formline designs onto the surrounding stand. In the following room, after Raven brings light to the world, projected scenes show birds flying into the sky and other animals in the forest. Sounds of nature mixed with human voices speaking in the Tlingit language can be heard. The light and sound “follows your journey,” Shuey says, and the combined effect accentuates the experience.”

Singletary and his studio artists created dozens of pieces for the exhibition while trying to maintain a lucrative business by making other pieces to sell. Some of the largest pieces had to be created in the Fire Art Studios in Portland because it had a larger kiln.

The end result was well worth the combined effort. Singletary has broken glass ceilings of how Tlingit art is perceived, and “Raven and the Box of Daylight” has educated a broad audience about North Pacific Coast cultures. Yet Belarde-Lewis says that what everyone takes away from the experience is their own interpretation: “We give the bones of the story. But what it means, we can’t tell you.” She does hope that visitors will learn to “appreciate old stories, whether that is Raven’s stories or just thinking deeper about their own. Experiencing other people’s stories is a fundamental way of recognizing each other’s humanity.”

Singletary is now looking to create “pop up” exhibitions at other museums around the country as well as art for public spaces in Seattle. Incorporating Tlingit culture into his art and working with other Indigenous artists around the world “has become one of the most fulfilling things I could have done. It connects me to family and the community. I learned so much by thinking about the art, the histories and the stories,” Singletary said. “It is just such an enriching process for me, to be a kind of ambassador of glass to the Indigenous community.”

Raven and the Box of Daylight

Weaving a Story

The story of Raven releasing or “stealing” the daylight is one of the Tlingit peoples of southeast Alaska’s most iconic stories. The basic storyline is similar across Tlingit communities, but distinct variations make each version unique to specific villages and individual storytellers. Each telling emphasizes different aspects of the same story, creating a unique treasure for the families, the communities and for all Tlingit people. The story you are about to encounter is a blend of these voices woven together. The specific details that influenced the version told here helped shape Singletary’s glass art and his vision for this ambitious endeavor. This exhibition adapts the ancient story, bringing it into the present, so we can imagine what Raven went through to bring light to the world.

The Tlingit name for Raven is Yéil. The story of Yéil ka Keiwa.aa (Raven and the Box of Daylight) unfolds through four areas: Along the Nass River, Transformation, Clan House and World Drenched in Daylight. The underlying messages of Yéil ka Keiwa.aa are about not only light entering the world, but also the values of forgiveness, family over possessions and accountability for one’s actions.

—Miranda Shkík Belarde-Lewis (Zuni/Tlingit), Independent Curator

The following is excerpted from “Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight” exhibition, which was organized by the artist, Preston Singletary, and Museum of Glass in Tacoma, Washington. It is guest curated by Miranda Belarde-Lewis. The multisensory visitor experience was designed by zoe|juniper.

Before here was here, Raven was only named Yéil. He was a white bird and the world was in darkness.

At nearly 3 feet tall, this totem pole encapsulates the story of the Raven, who receives the box of daylight from his grandfather, the clan chief below, and releases the sun. Yéil ka Keiwa.aa Lákt (Raven and the Box of Daylight), 2016; cast lead crystal, kiln-cast glass; 32.75” × 9.75” × 6 in”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

Along the Nass River

Yéil (Raven) decides that he will try and do something about the darkness, for himself and for the world. As he follows the Nass River, he encounters the Fishermen of the Night.

As Yéil approaches the canoe, the Fishermen greet him with their paddles standing straight up in welcome. The Fishermen tell Yéil of Naas Shaak Aank-áawu (the Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River): that he is a wealthy man, that he and his family live in a house filled with wealth, and that he has a beautiful daughter who drinks from the river every day. They tell Yéil the man has many treasures in his Clan House, including beautifully carved boxes that house the light.

Projected scenes, such as this one behind the salmon, canoe and its paddles on the Nass River, allow visitors to experience Raven’s world. Nass Héeni (Nass River), 2018; kiln-formed glass; steel feet; 5’ x 29’ x 14’. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

The white raven is a spiritual being. Visitors can follow his journey throughout the exhibition. Dieit Yéil (White Raven), 2018; blown, hot-sculpted and sand-carved glass; steal stand; 19.5” x 10” x 14”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

Transformation

Yéil knows he will not be welcome in his raven form and devises a plan to transform himself to a tiny speck of dirt. His plan is to float down the river into the drinking ladle of the young woman, Naas Shaak Aank-áawu du Séek’ (Daughter of the Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River). That is how he will sneak into the Clan House.

Yéil turns himself into a piece of dirt and falls into the water. He floats into the young woman’s ladle as she dips it into the river for a drink. Her servants test the purity of the water by dipping a feather plume into the ladle. Yéil in dirt form is discovered and thrown away. Yéil notices the color of the ladle is similar to the color of hemlock boughs. On his second try, he transforms himself into a hemlock needle and floats into her ladle again.

Yéil is ingested by Naas Shaak Aank-áawu du Séek’ and she becomes pregnant with Yéil. The family questions the Immaculate Conception, but ultimately accepts it. When it is time for the young woman to give birth, the servants line a shallow pit with fine furs in preparation for the high-ranking baby to be born. Naas Shaak Aank-áawu du Séek’ struggles and cannot give birth. A wise woman is summoned, and she notices the fine furs. She knows the finery is making the birth difficult and orders them removed. The furs are replaced with a more humble lining of moss and Old Man’s Beard from the trees, and Yéil T’ukanéiyi (Raven Baby) is born in human form.

Yéil T’ukanéiyi grows into a precocious and precious human boy.

Hoping to be ingested by a clan chief’s daughter and be reborn as a human boy, Raven turns into a speck of dirt, which can be seen as a small blue ball inside a drop of water dangling from a feather that stretches nearly 2.5 feet tall. Héen Alts‘ak (Feather Pulled Through Water), 2017; hot-sculpted and sand-carved glass; steel stand; 29.5” x 6” x 8.5”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

The Raven has more success as a hemlock needle and the daughter becomes pregnant. This statue shows the face of the raven baby on her belly. Below it is the moss on which he will be born. K‘anashgidéi Yā-x Koowdzitee (Humble Birth), 2018; blown, hot-sculpted and sand-carved glass; steel stand; 49.5” x 19” x 19”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

Clan House

Yéil K’átsk’u (Raven Boy) is the beloved grandson of Naas Shaak Aanáawu (the Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River). Naas Shaak Aanáawu spoils him, giving all he asks for; his grandfather cannot deny him. Even though he is given everything he desires, he tires of being a human and decides it is time to leave.

Three carved boxes contain Naas Shaak Aank-áawu’s most prized possessions: the stars, the moon and the daylight. Yéil K’átsk’u asks for the boxes and is told he cannot have them. He cries and cries for the box of stars and eventually his grandfather relents. Naas Shaak Aank-áawu gives his grandson the box of stars, which he immediately opens. The stars slip through the smoke hole in the Clan House and take their places in the sky.

Naas Shaak Aank-áawu is furious with his grandson. He scolds him and Yéil K’átsk’u becomes inconsolable. His crying breaks his grandfather’s heart and he forgives his grandson for what he has done, but the boy still will not be comforted. The boy moves towards the box containing the moon. His grandfather hesitates, but forgives his grandson again. He gives Yéil K’átsk’u the box with the moon.

Naas Shaak Aank-áawu du Séek’ (Daughter of the Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River), the boy’s mother, does not think her son should have the box and she argues with her father. As they argue, Yéil K’átsk’u opens the box. He plays with the moon and then releases it. The moon silently slips through the smoke hole and takes its place in the sky. The sun is the final treasure. Naas Shaak Aank-áawu protects it fiercely, but Yéil K’átsk’u eventually succeeds in releasing the daylight.

Large pieces such as these clan house panels and posts can weigh hundreds of pounds and take days if not weeks to cool once fired. Naa Kahídi (Clan House), 2008; Kiln-cast and sand-carved glass; water-jet cut, inlaid and laminated medallion; screen 109” x 122” x 2.5”. Two house posts; each 81.75” x 32.5” x 2.5”. Collection of Museum of Glass. Photo by Russell Johnson and Jeff Curtis, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

The Clan House is full of precious objects that show the Nobleman’s wealth, such as this seal sculpture. Deenáa (Fur Seal), 2010; blown and sand-carved glass; 13.75” x 7” x 9.5”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

Light shining from above on this “transformation hat” shows its designs clearly on its stand. S’aaxw (Hat), 2018; blown and sand-carved glass; 6.75” x 16.5”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

The boxes are illuminated within with lights that make them glow. Behind the boxes, projected images of clouds and other scenes add to the ambience. Altogether, more than a dozen projectors were used throughout the show. Dis Lákt (Box with the Moon), 2018; kiln-formed and sand-carved glass; neon lighting; steel base; 20.5” x 30.75” x 18.75”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

In the Clan House are the chief’s most precious objects, carved boxes containing the stars, the moon and the sun. Keiwa.aa Lákt (Box with Daylight), 2018; kiln-formed and sand-carved glass; neon lighting; steel base; 16.5” x 35.75” x 14.75”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

World Drenched in Daylight

As the stars fill the sky and as the moon takes its place, light begins to fill the earth. When the sun takes its place in the sky, bringing daylight to the world, it is frightening to all those who have been in darkness. The people are able to see the world around them for the first time and are startled. Those wearing animal regalia run to the woods and become The Animal People. Those wearing bird regalia jump into the sky and become The Winged People. Those wearing water animal regalia become The Water People. Those who remained strong (and stubborn) become Human People.

Yéil (Raven) decides it is time to leave and transforms back into bird form. Naas Shaak Aank-áawu (the Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River) is devastated that his treasures have been released into the sky. He is so angry that he gathers all the pitch in the Clan House in a bentwood box and throws it into the fire. He catches Yéil as he tries to escape out of the smoke hole and holds onto his feet. Raven is covered in the soot and smoke of the fire. He is transformed from a spiritual being into the black bird we know today. His color marks his sacrifice; his physical form is forever changed for bringing light into the world.

The story climaxes with the Raven releasing the sun. His human grandfather, fed up with his tricks, holds him over a smoke hole, turning him black. Gagaan Awutáawu Yéil (Raven Steals the Sun), 2008; blown, hot-sculpted and sand-carved glass; 9.5” x 26” x 9.5”. Collection of the Museum of Glass; gift of the artist. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

Balance is important to the Tlingit world. When the light comes to the world, animals disperse into the sky, woods and water and people are divided into two moieties, under which are several clans designated by animal crests. Here are just two of the many noble leaders of those clans in the exhibition, Salmon Woman from the Eagle moiety (pictured here) and Thunderbird Man of the Raven moiety (next slide). Xaat Sháa (Salmon Woman), 2018; blown and sand-carved glass; 27” x 14” x 14”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass

Xeiti Kaa (Thunderbird Man), 2018; blown, hot-sculpted and sand-carved glass; 26” x 15.5” x 15.5”. Photo by Russell Johnson, Courtesy of Museum of Glass