Leaning into the driving sleet 15,700 feet above sea level, Hugo Escalante buries his head into a woolen shawl as he walks the hills of Picotani, his 200-person village in southeast Peru that is cradled by towering Andes mountains. This and two other nearby Quechua communities, Cambria and Toma, provide up to 20,000 acres of refuge for the vicuña, an animal that has been long been venerated in Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. To this day, it is a symbol of nobility and its wool is an economic lifeline for Quechua and other Indigenous communities in South America.

This animal has narrow legs, a svelte body and the ability to leap with such grace that it resembles an antelope. However, it is a camelid related to domesticated alpacas and llamas as well as its wild cousins, guanacos. Its cinnamon fur is offset by patches of white on its underbelly and chest. The vicuña is often seen holding its head up high, alert to threats. It is territorial to the extreme. With oversized eyes framed by long lashes, it has a penetrating, captivating stare. With a famed resistance to domestication, the vicuña is a regal symbol enshrined on Peru’s national coat of arms, postage stamps, paper currency and coins.

When Escalante looks at the snow-covered pasture, he is relieved as this year the vicuña have a better chance of surviving the dry season. As the traditional summer rains in the Peruvian Andes turn to sleet, then snow, the dusted fields and ancient stone homes look frozen in time. Snowflakes the size of cherries float down and blanket this valley high in the mountains 3 miles above sea level.

“Picotani is an oasis for the vicuña. We have been working with this animal for years,” Hugo Escalante said as he walked toward a skittish wild herd on the outskirts of the community. He described a devastating drought that struck the area in 2023, causing hundreds of the cherished vicuñas to die of hunger and thirst. “The worst is behind us,” he said in between chewing on coca leaves to combat fatigue. This recent snow, he explained, will allow grasslands to sprout and vicuñas to graze on their lands.

Living in this high altitude and cold is a constant battle. Gusts of frigid wind rip through these valleys, through which occasionally can be heard the warbling, high-pitched call of the vicuña. Locals dress in layers, keep gas stoves burning and acclimatize to the harsh life in the altiplano, the plateaus high in the mountains.

The stone homes—some roofed using thatched bundles of grasses—do have electric power, but the residents say it is sporadic. So Picotani runs on the cycle of the sun. This pastoral schedule is focused on the vicuña and the slightly larger alpaca, which has for centuries served as a valuable source of meat, pelts and woolen products, including socks, sweaters and scarves. Even the alpaca stomach is cherished, as once removed it can be cleaned and then filled with milk that later curdles into a coveted cheese. The vicuña was also once hunted for food and fur, but now it is protected.

Farmers have to keep an eye on their herds and so can be seen patrolling their fields. Pumas are an infrequent predator on their animals here, but once spotted, are often shot on sight. Foxes are more common, and frequently they will sneak up to the the alpacas' shelters and kill newborns. “I lost two last night,” fretted Hugo Escalante as he described how the recent snowstorm brought his guard dogs into the house and the foxes out for the hunt. “In the morning the dogs brought me what was left,” he said, lamenting the death of the newborn alpacas.

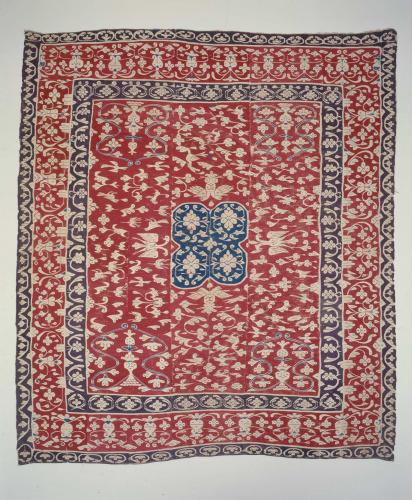

This harsh climate led the vicuña to adapt to the region’s high altitude by growing multiple layers of hair that provide insulation against the cold. As each hair is 20 times thinner than that of a human, this extremely soft fiber has been highly valued since the beginning of the Inca Empire in the 1400s. Woven into ceremonial tunics,“the use of vicuña clothing was in Incan times reserved for clergy and nobility,” said Vanessa Ocaña-Mayor, a Quechua-mestiza weaver and fiber artist who has a master’s degree in sustainable tourism as well as bachelor’s degrees in the fine arts and anthropology.

The vegetation around Picotani is sparse. Not a tree is visible in the entire valley and plants are rarely more than knee high. Still, this alpine ecosystem provides the local herds grasses for grazing and villagers sources of medicine. Sitting inside the town’s community center with a ball of coca leaves wadded in her cheek, Simona Yawa, one of Picotani's Quechua residents, casually rattled off the names of a dozen plants used to combat fatigue, infections, fertility issues and headaches. She also described the centuries-old practice of gathering muña leaves, which are then ingested either as a mintlike tea to combat altitude sickness or made into a balm to promote healing of colds and congestion. She also said that people in Peru still use the white fibers from the vicuña’s chest for healing ceremonies. The tufts of fibers are burned so that the resulting smoke can be inhaled to strengthen immunity and provide spiritual protection.

An Upward Climb to Recovery

According to the 2020 book “Vicuñas: Survival of the Finest,” an estimated 2 million vicuña roamed the Andean highlands during the 1400s. But following Spanish rule of the region, massive hunting and poaching over centuries whittled that number down.“The vicuña was on its way to extinction because of clandestine hunting,” said Jose Escalante, another Quechua resident of Picotani. “In this area in particular, there was not much interest in the conservation of the vicuña.” By the 1960s, only an estimated 6,000 vicuña remained throughout Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Peru.

The vicuña population was impacted further by a violent group in Peru known as “Sendero Luminoso,” or “Shining Path,” which killed tens of thousands of Peruvians from 1980 through the 1990s. Shining Path members often sought refuge in the southern Peruvian highlands, where they targeted the vicuña for food.

Given the extreme violence of Shining Path, many government offices and functions in the highlands were abandoned. Roads were not maintained and infrastructure improvements were postponed. Farmers were unable to transport their animal products to market, including vicuña and alpaca wool. Some villagers chose to live in caves as a tactic to avoid the bands of Shining Path hit squads. Noted breeders of alpaca and agricultural experts Orlando Barreda and Alberto Pumayala were murdered in 1992 near Picotani. The mayor of one village was executed in the town square.

The lack of government presence allowed bands of poachers to migrate in from Bolivia, slaughter alpacas and vicuña, and then retreat to relative safety beyond the Bolivian border. “In the late 80s, we formed self-defense committees,” said Jose Escalante. “It was difficult. We had not a rifle, and the hunters were well armed. It was difficult to confront them. It took time to earn the respect [of the poachers] and after that, the population of vicuña began to grow.”

The establishment of a nature preserve in Ayacucho, Peru, in 1967 for the vicuña called the Pampa Galeras–Barbara D'Achille National Reserve (named in part after environmental journalist Barbara D’Achille) as well as an international ban on trade of vicuña fiber in 1975 helped the animal recover. In 1992, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori codified the vicuña as property of the national government but transferred the right to shear them to the country’s Indigenous communities provided the animals were not harmed in the process.

The Gathering of the Vicuña

Given that vicuña are fleet of foot and wild, every year a ceremony known as a “chaku” (a nonlethal hunt) is held in villages where the animals live to temporarily catch them. The capture of vicuña is a sacred affair that does not even commence until the completion of a fertility ceremony. This begins with a “wedding” between a female and male vicuña, who are adorned with woven earrings and headdress before being paired at an altar and blessed. “We ask the Pachamama (Mother Earth), our creator, to keep giving us more babies,” said Hugo Escalante. “We always ask for the next year for there to be more births and more fiber.”

During the chaku—a ceremony that is estimated to date to 1200 A.D.—the villagers herd the animals together by using long cords of twine adorned with flapping colorful flags and walking slowly toward the center. From above, the human circle looks like a slow-motion tsunami rolling inwards. The line of encroaching humans looks insurmountable, yet the vicuña try to break through the lines. Some do leap past the startled humans, but these can be quickly herded back toward the center. All are eventually directed toward a chute that leads them into a corral where they can be sheared. Once they are sheared, they are released.

The local residents treat the animals with care during these roundups and do not brand them. “We always trying to protect this species. We are a strong believer in this ceremony.” said Pedro Mullasaca, the Quechua president of Picotani.“The vicuña brings us together. We should value it more,” he said. “For our community, this is much more than just fiber.”

The land from which the vicuña must be rounded up is vast, and evaluating each vicuña to determine if it is healthy enough to be sheared is time-consuming. “The [Picotani] community has thousands of vicuña,” explains Alejandro Tejeda, a Quechuan community member who has worked on various projects for Picotani, including water conservation initiatives for vicuña pastures. Tejeda explained that for every thousand vicuñas, only about a third are eligible for shearing. Some are pregnant, while others are too skinny. Unless the animal’s coat is robust, shearing may cause it to freeze as it would be unable to shield its core temperature from the region’s bitterly cold wind.

During the chaku, celebratory meals that might include alpaca ribs grilled over coals are held between tasks. While the shearing process is completed in one day, the event may last several. Then the women in a community will spend weeks removing burrs, dirt and other imperfections from the sheared fibers. The work is meticulous, and a full month of cleaning leads to just about 2 pounds ready for market.

Given the amount of effort necessary to celebrate and protect the vicuña, Mullasaca is worried his people's traditions could be lost. “There are some youth who are interested, but not with the enthusiasm or the spark we have,” he said. “We have to work with the preschoolers, the elementary and the high schoolers so that they have a deeper understanding of the vicuña.”

A Delicate Market

The ban on international trade of vicuña wool was lifted in 1995. Protection of the vicuña soared in the late 1990s, when the Peruvian government spearheaded an international bidding process that encouraged luxury clothing brands to make their best offers for the animal’s wool. Italian luxury brand Loro Piana won the bid with an initial five-year commitment to buy all the vicuña wool that communities produced, invest $1 million in the machinery needed to process it as well as market any resulting products. Today, fine vicuña wool is among the most coveted fibers on Earth. Compared to the finest cashmere that is about 19 microns thick, the vicuña is just 12 microns yet still strong. As weaver Ocaña-Mayor explained, “It is unmatched in texture, luster and tensile strength.”

Sold around the world by high-end brands such as Louis Vuitton and Ermenegildo Zegna, a single vicuña fiber jacket or shawl can cost thousands of dollars. Vicuña baseball caps (which were recently made famous when used by actors on the television series “Succession”) are selling out at $600 each.

Every year, Tejada said that Picotani receives tens of thousands of dollars from its sale of vicuña fiber. All the money must be spent on community projects, such as a schoolhouse for the children or watering holes for the wild vicuña. Individuals such as Yawa keep their personal finances afloat through their herds of alpaca, each worth about $300. “If I need a thousand dollars, then I sell three alpacas,” explained Yawa, who estimated her current stock of alpaca at roughly 200 animals.

In Picotani, the economy isn’t necessarily dependent on a monetary system. Neighbors trade supplies, lend animals for breeding and share the costs of feed and transport. In March, scientists visiting from the National Agrarian University–La Molina in Lima provided local leaders with an ominous evaluation: the highlands were overgrazed and needed time to recover. For those living this pastoral tradition, this was unwelcome news, as they seek to increase the density of vicuña near the community.

Poachers also continue to be a threat, said Mullasaca. They shoot the vicuña, skin them and leave behind the carcass. Often they kill 10 to 20 vicuña per raid, which explains the written signs posted around the perimeter of Picotani that warn intruders they face armed patrols.

These challenges, however, have not weakened the community members’ commitment to the vicuña or their faith in Pachamama. “Be it the grasses, the vicuña, our own food supply, we thank her [Pachamama] for bringing these living things into existence,” said Yawa. “The vicuña has always been present in the different episodes of our life, and we have a deep conviction to conserve the vicuña.”