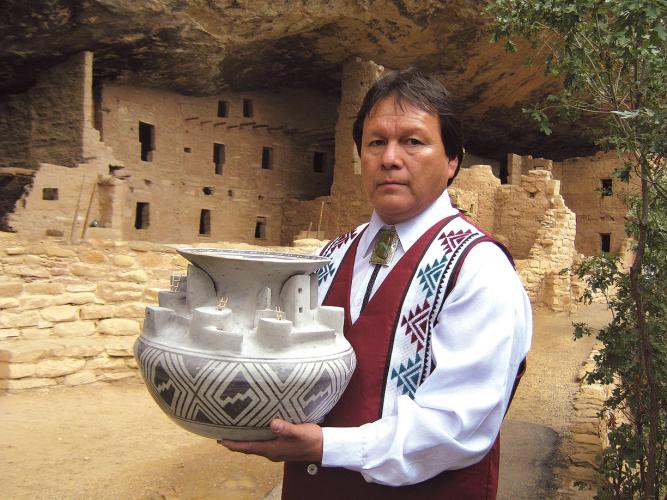

Joshua Madalena made a hard choice in the early 1990s. An accomplished potter and religious and political leader from the Pueblo of Jemez in New Mexico, he decided to devote himself to reviving his people’s ancestral black-on-white ceramics.

The art form had been lost for nearly three centuries. But after a decade of experimental efforts, he successfully rediscovered the process.

Madalena believes that the unique Jemez ceramic pottery is the original art form of his Jemez people (pronounced hey-mess). “It is the pottery of the ancestors. It was the dominant art form of the Jemez people for 400 years, and survived without change during that time,” says Madalena. But when he started his quest, he said, “There was no memory from anyone (within the Jemez community) that I could use as a resource.”

This unique pottery is tempered with volcanic tuff or rock, slipped with white clay, painted with carbon (vegetable) paint and fired in an oxygen-free atmosphere. Archaeological findings show that the pottery was used from about 1300 to 1700 A.D. throughout the Jemez Mountain range and surrounding areas, before being extinguished by Spanish occupation of what is now modern-day New Mexico.

“Contemporary art changes from one generation to the next, but Jemez black-on-white pottery didn’t change for 400 years,” says Madalena. “These vessels were created from miniatures all the way to giant form.

“Our pottery had been gone for 300 years. It needed to be reborn because I needed to find the identity of our people. I needed to find where I stood in this world and where my place was on Earth during these times,” says Madalena, a trained archaeologist. “This culture, these stories, needed to be brought back.”

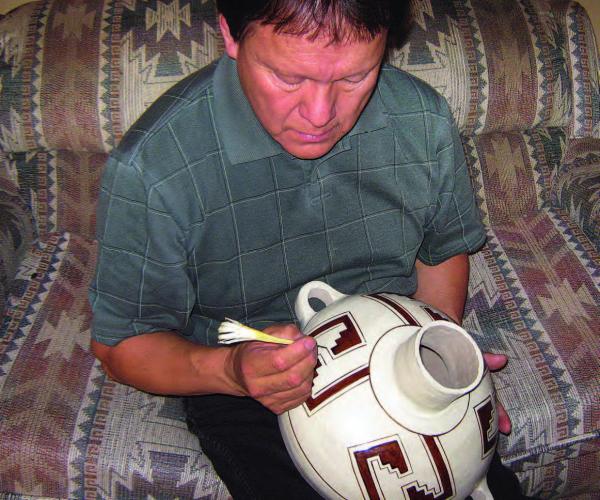

But recovering the process was an arduous and frustrating task, he recalls. “I started visiting museums and collections in Santa Fe and throughout the Southwest in the early 1990s. We had to find the right clay and plants, how long to boil them and so on.

One thing I did was I picked up pieces of old pottery in the different villages and took them up to Santa Fe to the Office of Archaeological Studies to take a look through a microscope. There were experts who could only guess about the process. The most complex part of this whole process was finding the correct proportion of clay and minerals that could withstand the high temperatures of pit fires.

“The clay was melting at about 1000 degrees when the pit fires were getting up to about 1800 degrees. I had to go through about a decade of trial and error before I thought the pottery was ready to go out into the public,” says Madalena, who currently resides in the Jemez Pueblo about 50 miles northwest of Albuquerque.

“I wanted to make sure that the public would be purchasing authentic, bona fide pottery of the Jemez people,” he adds. “This form of pottery had been lost for over 300 years and one of my biggest concerns was making sure it looked like the old vessels. I was able to accomplish that. What was once oppressed is now living again.”

It was an accident that finally resuscitated this ancient, traditional art form, Madalena says. “I was firing pots, and the large ones cracked, and it was sad. I had been working (on the pots) for about a month. I started throwing the hot dirt on top of all the pots. The next morning I went out to uncover the smaller ones, and I couldn’t believe it.

“They held together and it was the first time that I had seen a contemporary black-on-white that came out almost perfect. I feel like I solved a whole puzzle that had been missing for 300 years.

“Things happen,” he says, “and if something is meant to be, if it’s meant to happen then in some way or some form you’re given a gift by the spirits.

“You had your utilitarian wares, but the black-on-white pottery was designed with a sacred animal or our sacred mountains, valleys and canyons – our sacred places of worship. So the black-on-white pottery actually tells a story. It was the individual potter’s way of interpreting their times and the activities going on in their life,” says Madalena.

After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and the Spanish reconquest of the Southwest, Jemez black-on-white pottery was one of the casualties of Spanish oppression. Spain tried to suppress the traditional way of life of American Indians and especially the people in the Jemez region. They targeted the Native language and traditional religion, so it was taken underground. The language was spoken and the religious practices were performed in secret.

“For me to say that this pottery was authentic, my whole belief was that it was bringing back a culture that was once oppressed by another religion. This pottery is an identity for our people, for our culture and our survival,” says Madalena.

“That’s one of the things that really kept me going. It’s not something that we stopped. It was not our choice. Someone else forced us to stop doing this art.”

He continues, “Back in history it wasn’t just a form of art, it was a way of life. We used the pottery for storage of our food and for cooking purposes. It was an important issue for me to bring it back and I knew I was very close. I imagined that if I could bring back this art form that it could be utilized as part of our traditional way of life again.”

But Madalena also wants to bring the art form to the broader mainstream culture, as a means of furthering Jemez preservation. “I wanted to make it available for public purchase because of my background in archaeology,” says Madalena, who is also trained in archaeological law enforcement. “We were fighting against the looting of archaeological sites.

“We were also trying to fight against the black market. So, if we were successful in bringing back Jemez black-on-white pottery the general public would be able to purchase it over the counter.”

Madalena says that when he was growing up he did a lot of reading, and discovered that a lot of the Jemez history wasn’t written. During his research he noted that a lot of information about the ancient Jemez villages wasn’t accurate.

“It was usually non-Indian archaeologists who were documenting and identifying different information. That concerned me. I wanted to educate the general public that the Jemez people and the empire that our ancestors built in the Jemez Mountains were dignified,” he says.

Madalena was awarded the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Allan Houser Legacy Award at the Santa Fe Indian Market in 2012 for his contributions to the Native art world. In addition to his three one-year terms as Governor of Jemez Pueblo (in 2010, 2012 and 2014), he also served as Superintendent of the Jemez State Monument from 2005 to 2008.

“We have these laws and legislation in Congress that affect the indigenous way of life. We have laws in place today that protect archaeological sacred sites and places – places of worship that are still utilized today,” he says. “I believe that we as Native people have been very successful here in this region at establishing ourselves and holding federal agencies accountable of taking care of our land. We definitely have input.”

Madalena’s public career and his artistic work have been all of one piece. “One of the things that all pueblo leaders do,” he says, “is we try to fix the wrongs of the past.”

Madalena’s new website is www.ancientsart.com.