George Morrison (Grand Portage Band of Chippewa) has been called the “grandfather of Native Modernism”; he kept deep connections both to 20th century abstract expressionism and to his home-land on the north shore of Lake Superior.

Morrison was part of that bohemian world of post-World War II painters and beat writers who hung out in Greenwich Village at the Cedar Street Tavern. He also had deep connections to his Chippewa homeland and the ages old Spirit Little Cedar Tree near Lake Superior. As an artist and a Native man, he was the composite of many places: cosmopolitan, urban, activist, world traveler, teacher and intellectual. His world included both the Cedar Tree and Cedar Tavern.

For most Natives, the connection to the land and tribal community informs their worldview and animates the way they live. As important as these traditional, long-standing connections may be to Indians, and contrary to some of the stereotypes about them, they also are connected to a global world with all its complexities. As revealed in the lives they lived and the art they made, many Native artists drew inspiration from the duality of their particular homeland and its deeply personal tribal roots, as well as their worldly experience. This intersection of the Native Universe and the art world is very much in play in two current exhibitions on view at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York.

The Museum, on Battery Park in lower Manhattan, is the first leg of a major national tour of Modern Spirit: The Art of George Morrison. Organized by the Minnesota Museum of American Art and Arts Midwest, with the Plains Art Museum, Modern Spirit includes many of Morrison’s most visually stunning paintings, works on paper and wood collages, and follows his artistic journey and career throughout most of the 20th century. W. Jackson Rushing III, one of the most brilliant scholars and writers working in the Native art field, is the curator. It will be on display here from October 5, 2013 through February 23, 2014 and will continue on national tour through 2015.

Simultaneously in an adjacent gallery, the Museum is presenting Before and after the Horizon: Anishinaabe Artists of the Great Lakes, juxtaposing more than 100 contemporary and modern works with historic, ancestral objects revealing Anishinaabe life in the Great Lakes region. Running through June 15, 2014, it features Morrison along with other notable modern masters. (See Inside NMAI on page 48)

Morrison was born in 1919 in Chippewa City, an Indian village located on the north shore of Lake Superior, about two miles from Grand Marais, Minn. As the third of 12 children (only nine who survived childhood), and growing up in modest circumstances, he got his start as an artist carving pieces of found wood, making toys from castoff objects and junk, and making drawings by copying images from illustrations in books. He spoke his native Chippewa language until he began school. When he was nine, he was sent to the Hayward Indian School, a boarding school run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Hayward, Wisc.

Throughout high school, he worked for the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, mending books and making sets and scenery for plays. He enrolled in the Minneapolis School of Art at age 18. When he was 24, he moved to New York City where in his first years, from 1943 to 1946, he studied at the Art Students League. Five years later, he had his first solo exhibition in New York City at Grand Central Art Galleries.

Morrison embraced the creative artistic and bohemian worlds of New York, spent summers in Provincetown, and was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study in France in 1952. From 1963 to 1970, he taught at the Rhode Island School of Design. Upon his return to his home state in 1970, he taught at the University of Minnesota until he retired in 1983.

As artist Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee) articulates so well, Morrison “never made art with feathers and beads; he did not paint ponies and war bonnets; he did not paint about ‘identity politics’. (He) was an abstract expressionist.” In Morrison’s own words, “I always just stated the fact that I was a painter, and I happened to be Indian.” In the contemporary Native arts field, especially in the fine-arts domains of painting and sculpture, an ongoing polemic debates whether an artist is a “Native artist” or an “artist who happens to be Native.” Morrison certainly made art reflecting both his artistic era and his surroundings. His Native cultural roots were augmented by his training, artistic influences and where he lived much of his adult life. Clearly, his work expressed a profound cultural link to his direct experience on Lake Superior.

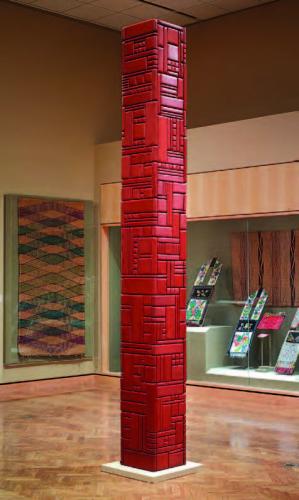

Although his home community was his primary Native place and “bohemian” New York City was where he matured as an artist, he also made Indian connections in New York and made plenty of art at home in the Great Lakes. Working with wood, including driftwood found on different shores, Morrison was a master of the collage and assembly. Artistically, he drew from all sources, yet he was true to his core. He lived in many different locations and always pursued his intellectual and artistic interests wherever he happened to be. He was able to find inspiration from all of the diverse sources, and all of them enriched and informed his work. Morrison’s connection to the land and the water was profound, as was his obsession with the horizon line. The result was powerful, culturally informed work.

Although Morrison avoided a market-driven Native style of art, he had considerable manual skills and knew how to construct and make things that were well crafted and polished. He had both an awareness of material and an interest in nature, especially water. Curator Rushing observes that Morrison was a Native artist doing non-traditional things; he was the first Native artist to respond to surrealism and deeply engage in abstract expressionism. Modern art is very much a tool to express Native content, and he did just that. There is a geometric quality evident in both his paintings and constructed wood pieces. Morrison avoided falling into the realm of the ethnographic. With a strong awareness both of European modernism and the post-World War II New York School, his work was highly structured, yet quite improvisational, which likely related to his interest in psychological investigation and the subconscious.

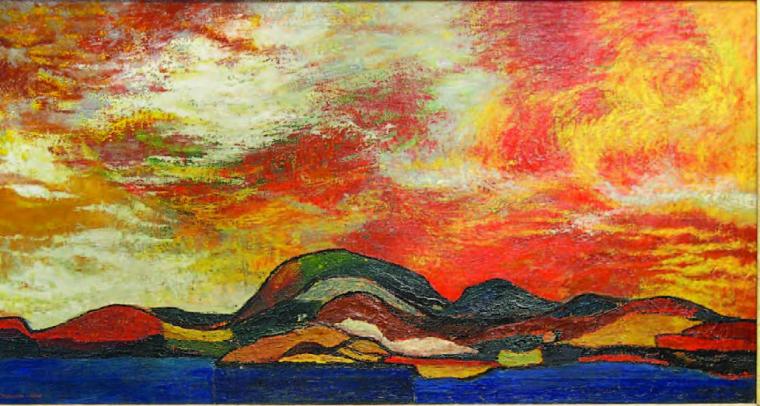

Coming of age as an artist after World War II, during a period when artists challenged what art looked like, and drawing from deep emotional and psychological sources, Morrison incorporated the styles of abstraction, expressionism, cubism and surrealism into his work. Yet, throughout his career, he was deeply engaged socially, culturally and politically with Indian people and concerns. Although there are no explicit and literal Native themes, icons, stereotypes or symbols in his paintings or sculpture, a close look at his body of work makes clear that the land, sky, air and water from his Indian homeland both inspired and informed what he created. The local and the worldly were both important influences (and complementary as well). While his paintings in particular are best understood within the context of abstract expressionism, the Native influences were present in his work throughout his entire career. Joe Horse Capture (A’aninin), associate curator at the National Museum of the American Indian, observes that Morrison’s surroundings were part of him, and his reservation informed his deep sense of place. Morrison had what Horse Capture refers to as a “Native spiritual backbone.” With his particular worldview, he had no need to be either militant or a victor. His contributions were visual, his legacy art.

As curator David W. Penney articulates in his introductory essay “Water, Earth, Sky” for Before and after the Horizon: Anishinaabe Artists of the Great Lakes:

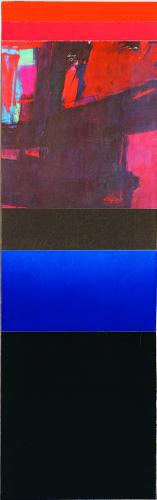

“Morrison created a visual language for painting based upon a lifelong commitment to modernist artistic practice and urbane experience as one of the leading practitioners of abstract expressionism. While worldly in technique (he studied and taught modern painting in universities), his work almost invariably references the sky, water, and shore of his Lake Superior homeland. The Red Rock paintings, named for his studio on the Lake Superior shore, offer introspective meditations on the transient light that shimmers over the elemental substances of rock, water, cloud and atmosphere. Weather- and water-worn driftwood add material and temporal dimension to his conceptual landscapes, arranged to create intricate shoreline topographies visible in Morrison’s many wood collages. Although initiated as a series while in New England, Morrison later said that the origin of the wood collages lay in his homesickness for the Lake Superior shore and his childhood habit of beachcombing, for driftwood. While Morrison eschewed any ‘Indian’ references in his work, was it plan or coincidence that his signature horizon line, the structuring device for nearly all his art, corresponds to the horizontal strata of the traditional Anishinaabe cosmos, which is composed of water, earth and sky?”

For the Anishinaabe, the relationship with the material world simultaneously shapes and expresses a distinctive Anishinaabe identity tied directly to place and a way of living. Morrison’s journey was global, yet always richly informed by his cultural base.

In 1985, when Morrison was in his mid-60s, he was diagnosed with a rare lymph system disorder, which he struggled with until his death in 2000. In special healing ceremonies in 1986, he was given two Chippewa names by his tribal elder and distant cousin Walter Caribou: Wah Wah Teh Go Nay Go Bo (Standing in the Northern Lights) and Quay Ke Ga Nay Ga Bo (Turning the Feather Around). How fitting that this exceptional non-objective artist who never made art with feathers was given this particular Native name! In his Red Rock Variation: Lake Superior Landscapes paintings, we viewers encounter the artist’s interpretation of this powerful northern light.

Morrison’s wife, Hazel Belvo, also an artist, confirms that for Morrison, being an Indian was “present in every part of his life and work.” This aesthetic was expressed in everything he did both in his daily life and his art. According to Belvo, Morrison had a richly informed intellectual life, loved reading The New York Times from cover to cover, had an extensive library and always kept updating his reading list. For Morrison, these literary connections were especially important and informed his work. He also was close to his contemporary artist colleagues Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still and Willem de Kooning, who he knew in New York in the 1940s and 1950s. One of Morrison’s large paintings (47" x 79") was hung in the home of Kline and was aptly given the title Red Painting (Franz Kline Painting). Like so many of the artists in his circle, he was interested in depth psychology and the work of Freud and Jung.

Throughout his life, Morrison was politically and culturally active in Native life both in his homeland and away from it. He frequently returned to his reservation and over the years, also served in teaching positions in his home state. He had close Native friends in New York, many who lived in Brooklyn, and he regularly went to Indian dances on 28th Street. In his early 50s – around 1970, the year when he permanently returned to Minnesota – he joined the American Indian Movement and even helped raise funds to support its work.

Looking closely at both his paintings and collages, it is clear that Morrison had a deep connection to his tribal roots, based largely on his direct experiences on Lake Superior and the surrounding sights and sounds. The significance of place is central to his work and daily life. From a formal perspective, he gave painterly attention to particular places. Technically, there was much layering of paint thickly applied on the picture plane, often with the effect of the horizon point extended far into the distance. Morrison was a strong colorist, using complex mixtures of rich and saturated colors, the deep colors present in his home landscape.

In the mid-1970s, he and Belvo acquired land near Grand Portage and built their home and studio, calling it Red Rock. This special place was about 30 feet from the north shore of Lake Superior and was where he continued working, through their divorce in 1991, and the difficulties of illness in his final years. He died in 2000, having returned to his own Native place.

The author acknowledges these two publications and the symposium as sources for this article:

Modern Spirit: The Art of George Morrison, W. Jackson Rushing III and Kristin Makholm, University of Oklahoma Press in cooperation with the Minnesota Museum of American Art, 2013.

Native Modernism: The Art of George Morrison and Allan Houser, edited by Truman T. Lowe, National Museum of the American Indian in association with University of Washington Press, Seattle and London.

Symposium: George Morrison: Art, Life, and Legacy, presented to mark the debut of the exhibition, Plains Art Museum, Fargo, N.D., June 16, 2013 (notes from presentations by W. Jackson Rushing III, Hazel Belvo, Joe Horse Capture, Colleen Sheehy).

The first comprehensive retrospective of a key Native modernist, Modern Spirit: The Art of George Morrison includes drawings, paintings, prints and sculpture that bring together concepts of abstraction, landscape and spiritual reflection in the mind and eye of this important 20th century artist. Half of the 80 works in the exhibition issue from the largest and most important collection of Morrison’s artwork in the country, the Minnesota Museum of American Art in St. Paul, Minn. The other 40 stem from important public and private collections from across the country. The exhibition is curated by W. Jackson Rushing III, Adkins Presidential Professor of Art History and Mary Lou Milner Carver Chair in Native American Art at the University of Oklahoma. Rushing’s teaching and scholarship explore the interstitial zone between (Native) American studies, anthropology and art history.

Modern Spirit: The Art of George Morrison is organized by the Minnesota Museum of American Art and Arts Midwest, with the Plains Art Museum. The exhibition and its national tour are supported by corporate sponsor Ameriprise Financial and foundation sponsor Henry Luce Foundation. Major support is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts and the generous contributions of individuals across the Midwest.