American Indians played a significant role in the coming of the American Revolution in its southern New England hotbed. Elsewhere some Indian nations chose the British side or attempted to stay neutral, but Indians of Connecticut and Massachusetts joined the Patriot ranks in the ferment leading to the Battles of Lexington and Concord as well as Bunker Hill in 1775 and fought throughout the war.

It might seem strange that the American Indians of this region fought in this war at all. In the two bloodiest wars of the 17th century – the Pequot War of 1637 and King Philip’s War of 1675–1676 – the area’s Indian population had taken heavy losses. In the 75 years before the American Revolution, these same Indian nations served the British in colonial wars against France, the wars known as King William’s, Queen Anne’s, King George’s and the French and Indian. Their service resulted in further depopulation. By the Revolution, the Indians’ vast landholdings in southern New England had been reduced to small enclaves.

Yet Hassanamisco Nipmuc, Mashpee Wampanoag, Mohegan, Pequot and Stockbridge Indians sent large proportions of their men to join the Revolution. Southern New England Indian participation continued well past the fighting around Boston. They were present in New York at Saratoga in 1777 and as late as the Battle of Fort Griswold in Connecticut in 1781. Many made the ultimate sacrifice. At least 26 Mashpee Wampanoag served in the Continental Army, 23 of whom served at the Battle of Monmouth in central New Jersey in 1778. According to missionary Gideon Hawley and Indian clergyman William Apes, no more than one Mashpee recruit survived the war.

Why did these Indians enter American military service between 1775 and 1776? These small Indian communities were surrounded by vast numbers of colonists who were fed up with English regulations, taxation and military occupation. The Indians of Southern New England reflected some of the attitudes of their white neighbors, in part because they were economically dependent on these pro-independence communities. The Indians were also heavily influenced by their Baptist, Congregationalist, Methodist and Presbyterian clergymen, who resented British efforts to give primacy to the Anglican Church of England.

The Incident on King Street, March 5, 1770

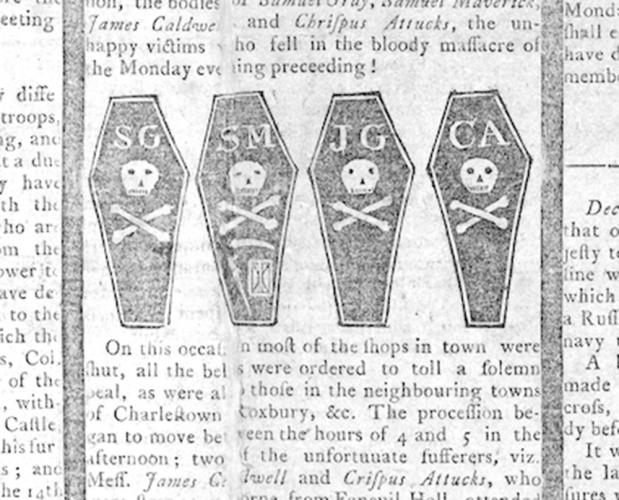

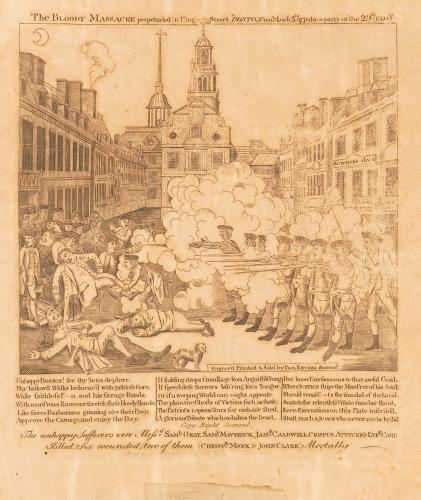

Since the time of the Sugar, Stamp and Townshend acts during the mid 1760s, American colonists were increasingly unhappy with British tax and regulatory laws. Tensions increased when a detachment of British troops was sent to Boston in 1768 to protect and support crown-appointed colonial officials attempting to enforce these unpopular laws. On March 5, 1770, an incident on King Street set American independence in motion. Amid ongoing tense relations between the population and the soldiers, a mob formed around a British sentry and subjected him to verbal abuse and harassment. The mob approached the government building (now known as the Old State House) with clubs in hand. John Adams, even though he later became a leader of the Revolution, served as defense attorney for the British troops put on trial after the incident. In his summation before the jury, which acquitted the soldiers, he called the crowd “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negros and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs [sic].” Although the sequence is still debated, the mob on King Street became increasingly agitated and threatening. Without official orders, the British detachment then fired into the crowd, instantly killing three people and wounding others. Two more colonists died later of wounds sustained in the incident. They became instant martyrs for the cause of Independence.

One of the victims, Crispus Attucks, is now a famous symbol of multiracial participation in the Revolution. He has been hailed by later writers as an African slave and is often labeled the “first Patriot to die in the American Revolution.” But it is highly probable that he was also American Indian.

We know from the Boston Massacre trial testimony that Attucks was a large man, about 6 feet tall, who worked as a sailor and on the city’s docks. He was at the forefront of the mob, brandishing a club and cursing at the British troops. In the racist outlook during the two centuries following the Revolutionary War, a person was considered to be “black, mulatto, or colored” if they carried a single drop of so-called “black blood.” By this standard, Attucks was deemed to be black.

But a recent scholarly book by Mitch Kachun, First Martyr for Liberty (Oxford University Press, 2017), questions this long-held assumption. Kachun concludes that Attucks was probably of mixed Indian and African ancestry and that he was born around 1723. He writes, “The case for Attucks’ Indian ancestors is circumstantial but strong. His hometown of Framingham, Mass., placed him very near Natick a ‘Praying Town’ of Christianized Indians from various Algonquian-speaking groups, founded by the 17th century missionary John Eliot.” The Indians of Natick were longtime allies of the colonists in wars against the French. In Massachusetts, these Praying Towns stretched from Cape Cod to Stockbridge. There were similar communities in Connecticut, New York and New Jersey. An estimated 17 to 21 Indians from Natick fought on the American side in the Revolution.

The Shot Heard ' Round the World

Growing Colonial resistance to the tax laws led to the famous Boston Tea Party on Dec. 16, 1773, during which colonists masqueraded as Indians and threw a cargo of British-taxed tea into Boston Harbor. In retribution the British Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts, also known as the Coercive Acts. This series of acts closed the port of Boston until restitution was made for the destroyed tea. The acts abrogated Massachusetts’ colonial charter and replaced it with a military government.

In April 1775, General Thomas Gage, who commanded the British Army in America, ordered Colonel Francis Smith and his 700 troops to capture and destroy military supplies that were reportedly stored by the Massachusetts colonial militia in Concord and arrest rebel leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock. At sunrise on April 19, the British troops – who the colonists dubbed the Redcoats for their uniforms – arrived in Lexington. On the village green, after the British ordered the vastly outnumbered colonial militiamen to lay down their arms and disband, a shot rang out. Eight Americans lay dead; the British suffered one casualty. About 11 a.m. at the North Bridge in Concord, a British soldier fired the first shot and approximately 100 of his comrades engaged with 400 militiamen. Two Americans and three British soldiers died in the exchange. The outnumbered British regulars fell back from the bridge, rejoined the main body of British forces and slowly made their way back to Boston. The militia then cut off the narrow access roads to and from the city. The war for control of Boston – and with it the American Revolution – had begun.

American Indians from the Praying Town of Natick, only 10 miles from Boston, were present along what later was referred to as “Battle Road.” Three of them were members of the Ferrit family – Caesar and his two sons, John and Thomas. Living in the Praying Town of Natick, they were of Indian, Dutch, French and African ancestry. Although they were described as “mulatto” in colonial records, the fact they gave their residence as Natick, the first and one of the most famous of the Indian Praying Towns, tells us much. According to a town history, they shot at British troops in Concord. Caesar’s occupation was as a coachman. In spite of being 60 years old when he enlisted in the Continental Army, the formal military force established after the Declaration of Independence, he served throughout the war. Nothing about his two sons is known except that when they were at Concord, Thomas was 24 years old and John was 22.

The Battle of Bunker Hill

After the fighting at Lexington and Concord, the ragtag colonial militia of about 15,000 men surrounded Boston. General Gage had failed to fortify the hills around the city, which was later to prove a decided advantage for the Patriots. However, the colonists lacked a navy and supplies, and they were unable to contest British control of the city. On May 10, 1775, General Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen, leader of the Vermont militia the Green Mountain Boys, surprised the British force at Fort Ticonderoga in New York. Although previously not included in stories telling about the capture of this historic fort, Stockbridge Indian warriors accompanied the American forces. Captured supplies and cannons were then transported by General Henry Knox over the Berkshire Mountains to the Patriot forces surrounding Boston. When mounted on the Dorchester heights, the new colonial artillery forced the British to evacuate Boston in March 1776.

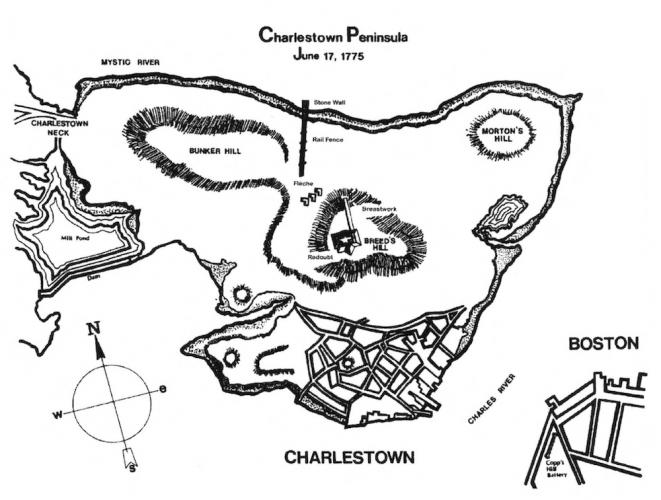

On May 25, 1775, three British generals – William Howe, John Burgoyne and Henry Clinton – arrived to deal with the rebellion. All would fail as military commanders during the Revolution. On June 16, General Artemus Ward and his 1,200-man army of Massachusetts colonists, including 104 “people of color,” marched from Cambridge to fortify Bunker Hill, which was a half mile from Boston and the dominant position on the peninsula. They arrived at a lower position at the foot of nearby Breed’s Hill, which was closer to Boston, and fortified it with an earthen redoubt.

On June 17, British forces began their land and sea operations against the American soldiers. As British ships began bombarding the town of Charlestown, General Howe prepared to land his forces. Howe and the British high command were excessively optimistic, believing that landing two regiments would be sufficient to beat the colonials.

Rather than focusing on the redoubt, Howe opted twice to initiate a frontal attack against the Patriots behind a rail fence, which was on the battlefield, perpendicular to the Mystic River. In preparation for the battle, the defenders had constructed a stone wall, extending the rail fence. In their two frontal assaults at this part of the battlefield, the Redcoats took heavy casualties and their lines of attack were broken. Their bodies were strewn across the battlefield. In a letter to his nephew, published later that year, Burgoyne called the battle “a picture and a complication of horror.”

Before initiating a third attack, Howe brought in fresh troops from Boston, stationed his artillery and ordered a bayonet charge against the central barricade of the redoubt. His third attack succeeded because the colonial forces ran out of ammunition. Exhausted and without supplies, the colonists attempted to fight back, some in hand-to-hand combat. This time British forces overran the redoubt. British grenadiers and light infantrymen pierced the American lines and drove the defenders over and around Bunker Hill.

Indians in the Battle

Behind the rail fence was an integrated company of American troops – whites, Africans and Indians – under the command of Captain John Durkee, Connecticut leader of the Sons of Liberty, the secret society organized in 1765 to fight British taxation. The company was assigned to guard the rail fence. In the first two British assaults, Durkee’s company held firm. George Quintal Jr. wrote a study that was published by the National Park Service in 2002 and revealed that at least 15 Indians fought at the battle. Eight were from Durkee’s company: John Ashbow, Samuel Ashbow Jr., Simon Choychoy, Jonathan Occum, Amos Tanner, Joseph Tanner, Peter Tecoomwas and Noah Uncas. According to Quintal, the eight Indians in Durkee’s company at the rail fence, all privates, were Mohegans and Pequots from the Montville-Norwich-New London area of Connecticut. Durkee apparently recruited them after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Samuel Ashbow Jr. was killed at the rail fence, one of three sets of brothers to die during the American Revolution. Simon Choychoy was 21 when he entered military service. Jonathan Occum, a 50-year-old recruit, was the brother of the famous Mohegan missionary Samson Occum and had previously served in the French and Indian War. Amos Tanner lost five brothers fighting in the Revolutionary War; Amos’ brother Joseph in Durkee’s company was apparently one of those brothers who was killed in the war. Peter Tecoomwas, then 26 years old, served off and on throughout the war but seems to have deserted in the late summer of 1780. Noah Uncas, a 32-year-old Mohegan, apparently died from an unknown cause sometime before the end of the war. Three other Indians not in Durkee’s company – Samuel Comecho, John Wampee and John Sunsiman – were also stationed behind the rail fence. Comecho, from nearby Sherborn, Mass., was reported to have died of smallpox later in the war. Although Wampee, a Tunxis from Pomfret, Conn., was not on any official company list, he is reported to have been behind the rail fence, perhaps volunteering his services just before the onslaught. Sunsiman (also recorded as Senshemon and Cinnamon and most likely of Pequot descent) was from the area around northern Woodstock, a northern Connecticut Praying Town known as Wabiquisset that John Eliot founded. Sunsiman later served under Captain Durkee’s command in other battles, including Monmouth Courthouse.

Other New England Indians served the Patriot Army at Bunker Hill. These included Alexander Quapish from Natick; Ebenezer Ephraim, a 27-year-old Hassanamisco Nipmuc from Worcester; Abraham Ephraim from Hopkinton and 20-year-old Joseph Paugenit, a Mashpee Wampanoag from Natick. John Chouen, of American Indian and African ancestry from Worcester County, was also among them. The 5-foot 5-inch private initially served as a minuteman and had enlisted after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Later in the war, records indicate that he deserted. More than half of the Indians of southern New England who were in the ranks of the Patriots at Bunker Hill – Privates Samuel Ashbow Jr., Samuel Comecho, Abraham Ephraim, Ebenezer Ephraim, Joseph Paugenit, Alexander Quapish, Joseph Tanner and Noah Uncas – were to die in combat or of disease during the war.

The battle was a Pyrrhic victory for the British. Approximately half of the British troops in the environs of Boston were casualties at the battle. According to the National Park Service, 268 British soldiers were killed and another 828 wounded compared to 115 Americans killed and 305 wounded. Although the British had routed the Americans, they had taken many more casualties, including losing a large number of officers. The Americans proved that an inexperienced militia was able to stand up to the formidable force of British regulars. In a report to the home government asking for more troops, Howe recognized the fierce determination of the Americans and predicted that the war would be a prolonged one.

But the New England Indians’ decision to join the Continental Army proved to be of no benefit in the long run. After the war their lands were encroached upon by the same Americans with whom they had served in the Revolution. Their so-called ally, the newly established United States, further diminished their sovereignty, allowing states to circumscribe their existence. Several of these nations – the Mohegans. Pequots and Wampanoags – were even denied federal recognition as “Indian tribes” until the 1980s and 1990s. The Mashpee Wampanoags only won recognition as a tribe in 2007 and are currently fighting legal battles to reestablish their reservation. Others such as the Nipmucs and Eastern Pequots have still been denied this status.