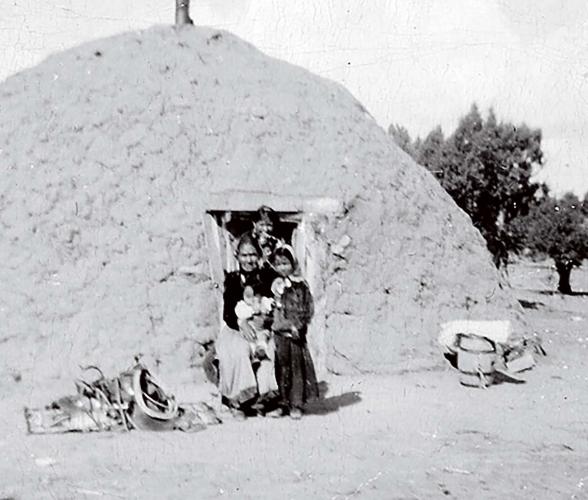

For Diné weaver and globally renowned fiber artist DY Begay, her greatest inspiration can be as close as the dirt beneath her feet or the sight of a mountain in the distance on her ancestral homelands on the Navajo Nation in Arizona. “Tsélání, or ‘the place of many rocks,’ is a stunning valley treasured by my Tótsohnii [clan] relatives and community members,” she wrote in one of her journals. “We have walked these formations while herding sheep, gathering medicinal herbs for ceremonies and plants for dyeing, and collecting drinking water. The Tótsohnii roots are grounded in this valley. Today, I am tracing the footprints of my ancestors as I, too, walk about this terrain, relishing its beauty.”

Born in 1953, Begay grew up on her Navajo Nation reservation in Tsélání, Arizona, within the embrace of her Diné people’s land, language and artistry. This cultural and familial wellspring is the foundation of her intensely personal process that creates vibrant landscapes woven together with memories. Begay’s innovative designs and the stories of her life and those of her ancestors are embedded within. For more than 30 years, DY Begay has been mastering her art, which is showcased in the exhibition “Sublime Light: Tapestry Art of DY Begay”—on view now through July 2025 at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.—and its companion catalog of the same name.

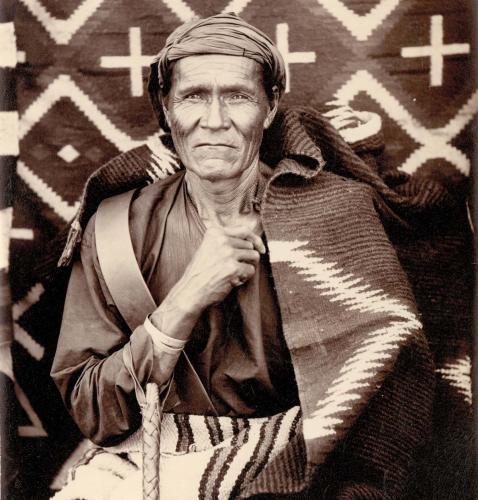

Begay shares a long history with the NMAI. Her relationship with the museum began with its predecessor, the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation (MAI) in New York City, and its historical collections. Having recently married and moved to New Jersey with her husband, Howie Meyer, during the early 1980s, she sought inspiration for her work, as she recalled, in “anything art related.”She found it in the 19th-century Diné “wearing blankets” on mannequins at the MAI. The term “wearing blankets” refers to woven dresses, mantas and robes worn by Diné during the 19th century. Diné robes referred to as “chief blankets” were often traded to other tribes. “I really stopped in my tracks,” she recalled, and then proceeded to investigate why they were there, how were they used, and where they came from.

Many such weavings of that time period were acquired by non-Diné collectors and not seen again by Diné community members. “I never knew that these historical textiles still existed,” Begay said. “I only knew about what my family was weaving and what I was weaving . . . so that was a turning point where I became more focused. . . . The museum was a great source of information. I needed to stay and learn as much as I could and it motivated me to focus on my own weaving, and that’s when a lot of those ideas—my personal journey—started to evolve.”

Following her revelation, Begay became an artist in residence at the MAI, which in 1989 became the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. DY Begay and other Diné weavers co-curated “Woven by the Grandmothers: Nineteenth-Century Navajo Textiles from the National Museum of the American Indian,” an exhibition that opened at the museum’s new venue in Lower Manhattan in 1996.

NMAI curator Cécile Ganteaume said she had the “unique privilege” of observing Begay’s development as an artist from those early days at MAI through the development of the “Sublime Light” exhibition. That Begay evolved her own aesthetic after exploring her medium is significant. “It’s a period where she’s intentionally exposing herself to a long and rich history of weaving as an art form throughout the world. She’s doing this because she’s innately curious,” Ganteaume said. “She’s playing it over in her mind, and it will eventually have an impact on her art. She has embraced weaving as an expressive art form—and a vital one, too.”

Weaving is fine art, and Begay’s innate curiosity about her own medium led her to travel the world to absorb the weaving and dyeing traditions of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists and cultures. Though she weaves on a traditional Diné loom using customary methods, this lifetime of research manifests in her innovative colors, dyeing techniques and designs.

In 2018, NMAI staff approached Begay about a retrospective exhibition of her tapestries. Ganteaume, art historian Jennifer McLerran and art conservator Jeanne Brako joined the project, lending their expertise as the curators for the exhibition. The resulting exhibition and publication do not isolate Begay’s artwork on blank walls and pages but rather places each in the context of the landscape and family memories that brought it into existence. “She conducts her life as an artist,” explained Ganteaume. “As she hikes through Tsélání, she is always attuned to its shifting colors and ready for that moment of inspiration. . . . Her art is about the feelings and memories the colors of Tsélání stir within her.” Whether abstract geometrics or undulating waves, Begay’s tapestries embody her life as a Diné woman in and of her homeland.

“My culture, my weaving tradition has been practiced for hundreds of years to sustain the culture, to sustain our lives,” emphasized Begay. That long history does not limit weaving’s evolution, however. Rather, the acknowledgment that 19th-century white traders tended to dictate design and materials for sales liberates contemporary weavers from conforming to the regional styles of the past. “I didn’t feel obligated, and I didn’t want to be put in a box or be labeled.”

Most important to Begay is the continuation of the art, which she said equates with the continuation of her Diné culture. “Even though we have all these outside resources like technology and transportation, the things that make our lives easier, if I can maintain tradition, I know I will survive. I will never go hungry.” Begay said. She wants people “to understand why we continue to weave, because it’s a big part of our culture—it’s the foundation of our culture.”

Shánídíín Bitahdę́ę́’ Hahóozhǫǫd: DY Begay Bidah Iistł’ǫ́ Baa Hane’

Sublime Light: Tapestry Art of DY Begay

The exhibition “Sublime Light: Tapestry Art of DY Begay” is the first in-depth look at Diné (Navajo) artist DY Begay’s vision and originality. A fifth-generation weaver, Begay’s transformative tapestries reflect her family tradition, her Diné identity, and the natural beauty of the Navajo Nation reservation where she grew up. Beginning with her earliest innovative tapestries through her contemporary work, the exhibition explores Begay’s artistic journey and how her art has been shaped by her unique approach to color, design, materials and sense of place.

Begay’s openness to other art forms and experimentation is a pervasive theme within her practice, but her most profound influence is Tsélání, her homeland on the Navajo Nation reservation. Using tools such as her hand loom, battens and hand-dyed wools, she combines her traditional Diné knowledge with the experience she gained from her global explorations of weaving. The result is her unique interpretations of her homeland and the world around her that are expressive of who she is as a Diné woman and contemporary fiber artist.

The catalogue accompanying the exhibition explores the central themes of her art—family, homeland and experimentation—in further depth through the story of her life. Co-edited by NMAI curator Cécile Ganteaume and art historian Jennifer McLerran, “Sublime Light” is the first publication to chronicle DY Begay’s three decades of innovation and experimentation. Both this book and the exhibition feature outtakes from Begay’s journals, family photographs and imagery from the Tsélání, Arizona, landscape that inspires her work. The first book devoted to Begay’s life and career, “Sublime Light” reveals the evolution of her work through her 80 evocative tapestries that she created between 1965 and 2022.

Following is a selection and adaptation of the vivid “Sublime Light” exhibition featuring Begay’s innovative artworks at the NMAI in Washington, D.C.

Bił Hahoolzhiizhídą́ą́ (Beginnings)

Begay’s artistic style evolved most significantly between 1994 and 2007. She initially worked within the customary Chinle regional style of Diné weaving but beginning with “The Natural” in 1994, she played with its design elements, stretching the terraced forms and incorporating colors from Tsélání. Begay expanded the boundaries of her art form, creating both figurative and abstract landscapes that were increasingly infused with emotion and memory in direct response to her environment.

“Around 1990 I realized I was honing my weaving skills but neglecting my passion for color and design. ‘The Natural’ flourished from this place in my weaving evolution. Sketching guided me. This was the first tapestry in which I embedded hints of colors from the landscape. It began my transformation into a new realm.” —DY Begay

“The Natural,” 1994; wool and plant dyes; 27.3"× 46.4". Private collection of Peg Maher and Bill Morgan. Photo by Walter Larrimore for NMAI

Tséláníjį’ Atsíná’iiłkees (Evoking Tsélání)

Tsélání, DY Begay’s ancestral homeland, exists for her as both an external and internal space. She experiences the land physically and within her mind, then reinterprets these spaces within her art.

“I can hear my neighbors calling to the sheep and I can see heaps of dust as the sheep race to the corral for their breakfast. These moments remind me of the stories about my great-great-great grandmother, Asdzą́ą́ Tótsohnii, who had over one hundred head of sheep and goats, and I’m sitting here visualizing the dust her sheep must have kicked up.” —DY Begay

“Tsélání,” 2000; wool and plant dyes; 37" × 55". Private collection. Credit: Photo by Walter Larrimore for NMAI

DDah Iistł’ǫ́ Yitł’óh Baa Hane’ Bee Bi’doolzį́į́’ (Mastering the Language of Weaving)

In pursuit of mastery, Begay has explored historical and contemporary weaving and dyeing practices as inspiration. Her designs are never static. She varies her creations between geometric, figurative and abstract tapestries.

“I’m inspired by colors from washes [dry stream beds] that I walk daily. [One] particular day we received some rain and the moisture restored and enriched the tired hues and soil designs. These land formations are dynamic movements—juxtaposing waves, like in the ocean. These natural events ignite my creative energy.” —DY Begay

“Natural Two,” 2010; wool and plant dyes; 33.7"× 50.2". Collection of Jürg and Christel Bieri. Photo by Walter Larrimore for NMAI

Begay took this image to capture the hues of the sandy clay soil of her Tsélání homeland. Photo by DY Begay

Like other Diné women, Begay will sometimes wear a biil (a two-panel woven dress) on special occasions. Wearing one, she says, grants her “protection, beauty, pride and recognition by the Holy Deities.” Biil doó Beeldléí: Asdźaní Bi Éé’” (woman’s garment), 2005; wool and plant dye; dress: 22.4". × 37.4"; manta: 25.5"× 43.5"; sash: 3.5"× 87.5". 26/6724. Photo by NMAI Staff

Ał’ąą Át’éego Nidaashch’ąą’ígíí Ayóo Atah Na’iiłnáh (The Emotive Power of Color)

DY Begay’s handling of color—a critical element of her creative process—is often experimental. She has used green dyes from lichen she sourced in Corsica and shades of red and purple from cochineal insects in Peru. Her work with dyes, whether traditional to Diné weaving or not, fuels her creative process. Geometric or abstract, Begay’s compositions demonstrate her focus on the volume, placement and interaction of color.

“Cheyenne Style was my first attempt to incorporate the bright colors and the geometrical designs inspired by my exploration of Plains designs. Parfleche artists believed that the uniqueness of this art emerges from the power of drawing. I kept that in mind as I incorporated the notion and the power of drawing with threads.” —DY Begay

“Cheyenne Style,” 2000; wool and plant dyes; 44.2"× 30.5". Private collection of Michael P. Morgan. Photo by Walter Larrimore for NMAI

“Cheyenne Style” was inspired by the geometric designs found on Diné chief blankets and possible (soft, multipurpose leather) bags, such as this one from the NMAI collection. Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) possible bag, circa 1850–1880; hide, glass beads, hide thong/babiche; 20/8711. Photo by NMAI Staff

Shánídíín Bitahdę́ę́’ Hahóozhǫǫd (Sublime Light)

In capturing the sublime beauty of dusk and dawn, DY Begay evokes within her weavings Diné values of giving thanks and prayer.

“My travel [in Peru] inspired ‘Palette of Cochineal.’ My dye experiments unveiled rich and unimaginable colors in my tapestry.” —DY Begay

“Palette of Cochineal,” 2013; wool and plant and insect dyes; 48" × 33" Gift of the Heard Museum Council in honor of Werner Braum, the Max M. & Carol W. Sandfield Philanthropic Fund of the Dallas Jewish Community Foundation as recommended by Norman L. Sandfield, and the Bruce T. Halle Family Foundation at the recommendation of Diane & Bruce Halle and in honor of Harvey and Carol Ann Mackay, Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona. Photo courtesy of Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

Sunset from Begay’s hogan in Tsélaní, circa 2009. Photo by DY Begay

Ła’ Asdzį́į́dóó Saad Bee Ha’oodzíí’ (A Singular Voice)

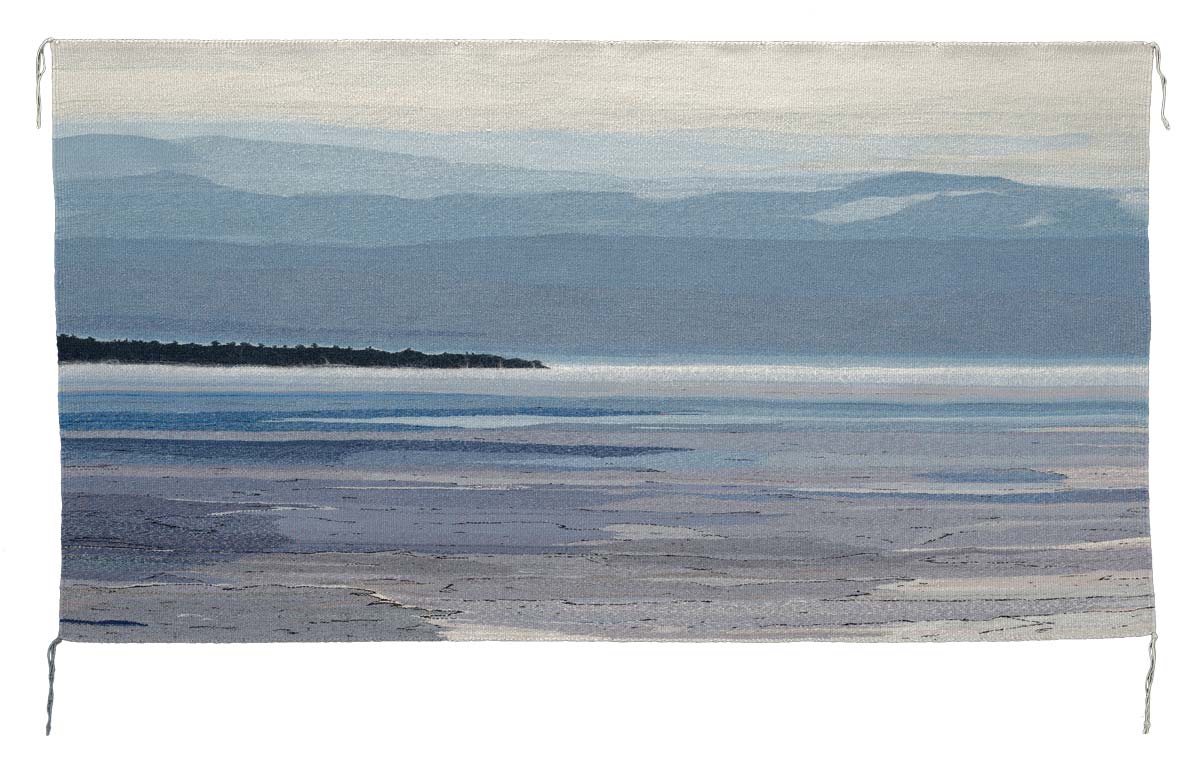

In creating “Winter in the North,” Begay accepted the challenge of depicting a northern environment foreign to her. Though she rarely depicts realistic landscapes, Begay not only captured the essence of an icy winter day but also the clear contours of a wave-swept shoreline at the edge of a misty, deep lake.

“My work largely focuses on abstraction and interpreting what unfolds in my surroundings of landscapes, the horizons or subtle transformations of clouds and sky color and reflective imagery.” —DY Begay

“Náhookǫsjí Hai (Winter in the North)/Biboon Giiwedinong (It Is Winter in the North),” 2019; wool, mohair, cotton, silk and linen, and plant dyes, 57"x 31". Collection of Minneapolis Institute of Art, The Jane and James Emison Endowment for Native American Art, Collection No. 2019.41. Photo courtesy of Minneapolis Institute of Art

Begay created this composite photo as reference for her work “Náhookǫsjí Hai (Winter in the North) / Biboon Giiwedinong (It Is Winter in the North).” Photo by DY Begay