In many homes today can be found an archive—a compilation of scrapbooks full of photographs lovingly assembled, caches of cell phone images and boxes of letters, files of other family documents. These preserve memories, connect our present to our past and help tell our stories.

The National Museum of the American Indian has one of the most comprehensive archives of documents and images depicting Indigenous lives across the Western Hemisphere. Its Archives Center serves as the steward of manuscripts, correspondence and other paper records as well as thousands of sound and audiovisual recordings dating from the late-19th century to the present. Yet the most prominent part of this collection is its more than 500,000 photographs. These images—which range from the first daguerreotypes created in the 1840s to digital photos—document Indigenous arts, politics, community knowledge, social and political movements and, just as importantly, views of everyday Native life.

At the NMAI in Washington, D.C., visitors are being offered a glimpse into these lives through “InSight: Photos and Stories from the Archives,” the first exhibition of photographs from the museum’s archives in more than 20 years. This selection of historical and contemporary images combined with stories from family members, Indigenous photographers and the museum’s archivists reveal rich details about the featured individuals and families. “We wanted to show something different than the stereotyped image of Native peoples that was always represented in earlier museums,” explained NMAI archivist Nathan Sowry.

In one 1918 image, for example, a young Chickahominy girl proudly shows off her doll. In a 1951 color photograph, two Iñupiaq women pick flowers on a summer day in Alaska. These scenes could be from any home today. “We wanted to find photos that were relatable,” said NMAI’s Head Archivist Emily Moazami. “We wanted visitors to be able to see themselves in the photos.”

Widening the Lens

George Gustav Heye, who founded the NMAI’s predecessor, the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation in New York, began assembling the archive in 1922 as part of his endeavor to amass a comprehensive collection of Indigenous material culture that represented the entire Western Hemisphere. Heye recognized photography as a powerful medium for documenting his growing object collection and the breadth—but not necessarily the depth—of Indigenous peoples and cultures. Photos served as a record of items in the collection and how they were created or used. Who the individuals were, however, was less important to Heye and those who acquired images and other items for him.

At the heart of the Archives Center’s work today is its partnership with Native peoples, in part to fill in this often missing but vital information. “Telling these stories is a collaboration between the archivist and Native peoples, their families and their communities,” Sowry emphasized. Native people consult with the archivists to document the collections from an Indigenous perspective. They donate materials, correct inaccuracies and share personal histories and community knowledge.

“It’s really about listening,” said NMAI archivist Rachel Menyuk. “When an Indigenous community member comes in, it’s about putting aside this idea that we’re the experts and instead sitting with them and listening to what they have to say.” This creates a deeper understanding of the historical and contemporary lives of Native peoples and, according to Sowry, “helps us tell better stories.”

As part of their work in the archives and on the exhibition, Menyuk, Moazami and Sowry have strived to expand Heye’s perspective and humanize the Native people in the photography collections. The Archives Center houses photographs of important tribal leaders and events but, according to Moazami, the real finds in the collection are the photos by amateur photographers such as missionaries, teachers, anthropologists and collectors. These individuals were often immersed in Native communities. As a result, their photos “tend to show more candid imagery, daily life and a wider swath of people,” she said.

Reuniting Relatives

The Archives Center makes images and documents accessible through a variety of avenues, from blog posts and exhibitions to searchable databases. Native families and communities who can identify people, places or items in the images can then add personal, family and community knowledge to the archival record, which is then preserved for future generations.

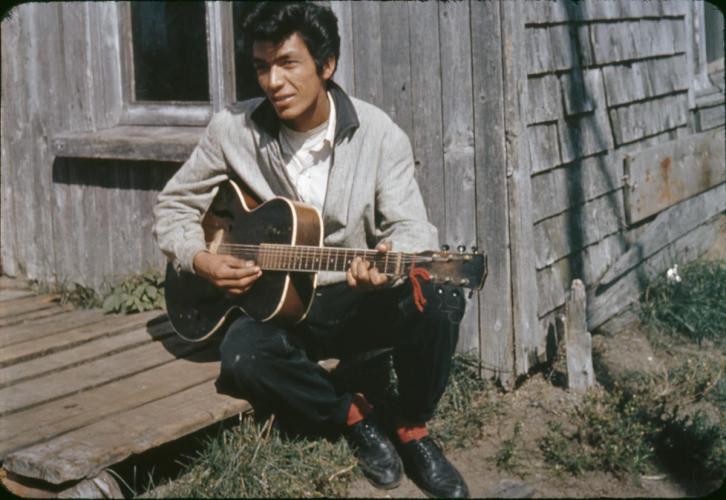

For instance, one photo in the exhibition shows Innu musician Thommy Mestokosho holding a guitar and sporting a sleek pompadour, looking like a 1950s rock n’ roll star. The photo was taken in 1959 by William F. Stiles, a former curator of collections for the museum who spent time among the Innu people in Québec, Canada. Stiles corresponded with Mestokosho from 1964 to 1968. The letters, which are housed in the Archives Center, reveal a personal relationship between the two men. Mestokosho frequently asked Stiles to send him guitar strings, because the shops near his village of Ekuanitshit (Mingan) didn’t sell them.

Nearly 60 years later, Lydia Mestokosho-Paradis came across the photo of Thommy Mestokosho, her grandfather, in a NMAI blog. She noticed his name was misspelled and reached out to the Archives Center staff, who corrected the error in the files. The archivists also sent her copies of the image and letters Thommy wrote. Lydia then shared details about his childhood, his love of music and the playful relationship he had with her grandmother. She thanked the NMAI for preserving Thommy’s letters and his photo. “We are grateful to know that the [museum] was able to keep these precious exchanges demonstrating the life of the 1950s to 1960s of Ekuanitshit. We have a wonderful oral tradition, but having pictures to complement these stories makes it even more wonderful.”

This chance encounter with a photo is just one example of the reciprocal exchanges between the Archives Center and Indigenous peoples. “One of the most rewarding parts of our jobs is when we interact with somebody who discovers a photograph of their relative,” Moazami said. “It’s an honor for us to be able to be a part of that journey for them to be reunited.”

Restoring Identities

One of the most arresting images in the exhibition is a black-and-white photo taken in 1910 of a young Apsáalooke (Crow) girl sticking her tongue out toward the camera. The photo was originally labeled only with the words “Woman in costume.” The archivists were drawn to the image, but not until Menyuk made an accidental discovery in the Archives Center’s cold storage did they start to unravel the mystery of this young woman’s identity.

Sorting through images, Menyuk found an old envelope. Written on the front was the name “Sarah Grandmother’s Knife,” and inside was the original negative. From there, the archivists went down a rabbit hole of genealogical research. They learned that this “woman” was in fact a 10-year-old girl. They traced her life from her childhood on the Apsáalooke reservation in Montana to her marriage to John Gros Ventre and later Harry Don’t Mix (together with whom she had eight children) and finally to her passing from cancer in 1957. The archivists hope that restoring Grandmother’s Knife’s name and family ties will help her descendants find her and add to her story. “Archives are dynamic,” Menyuk said. “They provide a place to find new stories and see new perspectives.”

The stories in this exhibition represent just some of the ways the Archives Center elevates Indigenous perspectives and voices within the photography collections. The NMAI keeps the stories of Native people safe through not only preservation but also accurate documentation. It increases the public’s understanding of Indigenous experiences and helps Native families and communities reconnect with material that documents their heritage. They can then share these materials, add their own knowledge or take knowledge back to their communities. The photo collections have been used to research and revitalize ceremonies, artistic techniques, traditional food production and other lifeways that have changed or faded over time.

This ongoing exchange between the Archives Center and Native peoples centers the archives as a transformative space where Indigenous stories are found, written and rewritten, and shared across locations and generations. Photo historian and the NMAI’s Acting Associate Director of Scholarship Michelle Delaney said, “There are so many hidden gems within the collections. We’re only at the tip of the iceberg when it comes to researching the stories in the archives.” History is made up of more than just big, impactful events. “It’s the everyday moments,” reflected Delaney, “the daily work, the daily joy, and the trials and hardships that give a fuller picture of our past.”

InSight: Photos and Stories from the Archives

The Archives Center at the National Museum of the American Indian stewards more than half a million photographs. The center works to reconnect Indigenous communities with photographs, papers, and audiovisual recordings that document their heritage. Through research and open dialogue with the archivists, Native people share community knowledge and reunite faces with names and family histories.

Archival images give an intimate view of Indigenous lives across the Western Hemisphere and across time. They show not only leaders and important events but also everyday moments of joy and quiet reflection. In them, people attend social gatherings, pose for family photos, and learn from relatives. Each photo has a story to tell. It’s the rich insight shared by Native people that brings these stories to life.

The following is adapted from the “InSight” exhibition on display at the museum in Washington, D.C.

Made for Sharing

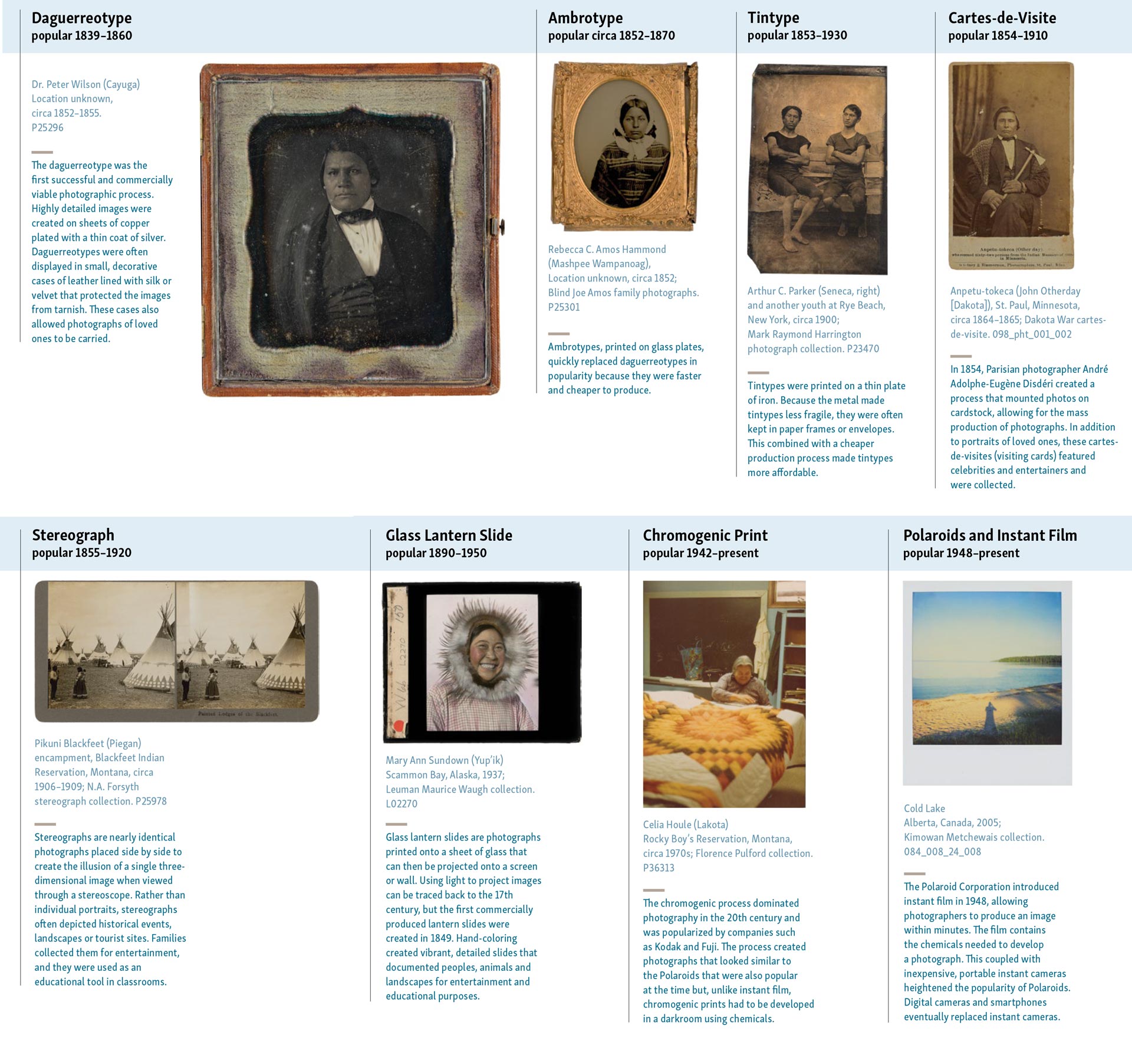

The invention of photography created a new way to record events, people, and places and share experiences. Looking at photographs leads to reminiscing, talking and enjoying memories together. When photographs are preserved and made accessible in an archive, they have the power to be shared across generations.

The Archives Center stewards photographic formats dating from the 1839 invention of photography to today. As technology improved, formats changed and access to photography equipment became widely available.

Behind the Image

Some photos in the Archives Center are attached to other materials—such as letters or interviews—that enrich their stories. Just a name, location or generic description help identify individuals. Photos with little or no documentation provide only glimpses into the stories behind the images. A sewing circle implies a communal bond shared by women from different Apache communities. A moment between a grandmother and her granddaughter suggests knowledge and skills passing from one generation to another.

The archivists continually work with Native families and communities to add information to the photo collections. It takes time, relationship building and collaboration to tell the real story behind an image.

Many photos in the archives document objects that are in the NMAI’s collection, such as this mortar and pestle. Here, Clara Schuyler watches her grandmother Julia Pahbahmowatong (Ojibwe) prepare food using the mortar and pestle. Sitting on the ground behind Clara is a container made from birchbark and spruce root that is also part of the museum’s collection.

Julia Pahbahmowatong (Ojibwe) and Clara Schuyler, Wasauksing Reserve (Parry Island Reserve), Ontario, Canada, 1928; Frederick Johnson photograph collection. N14452

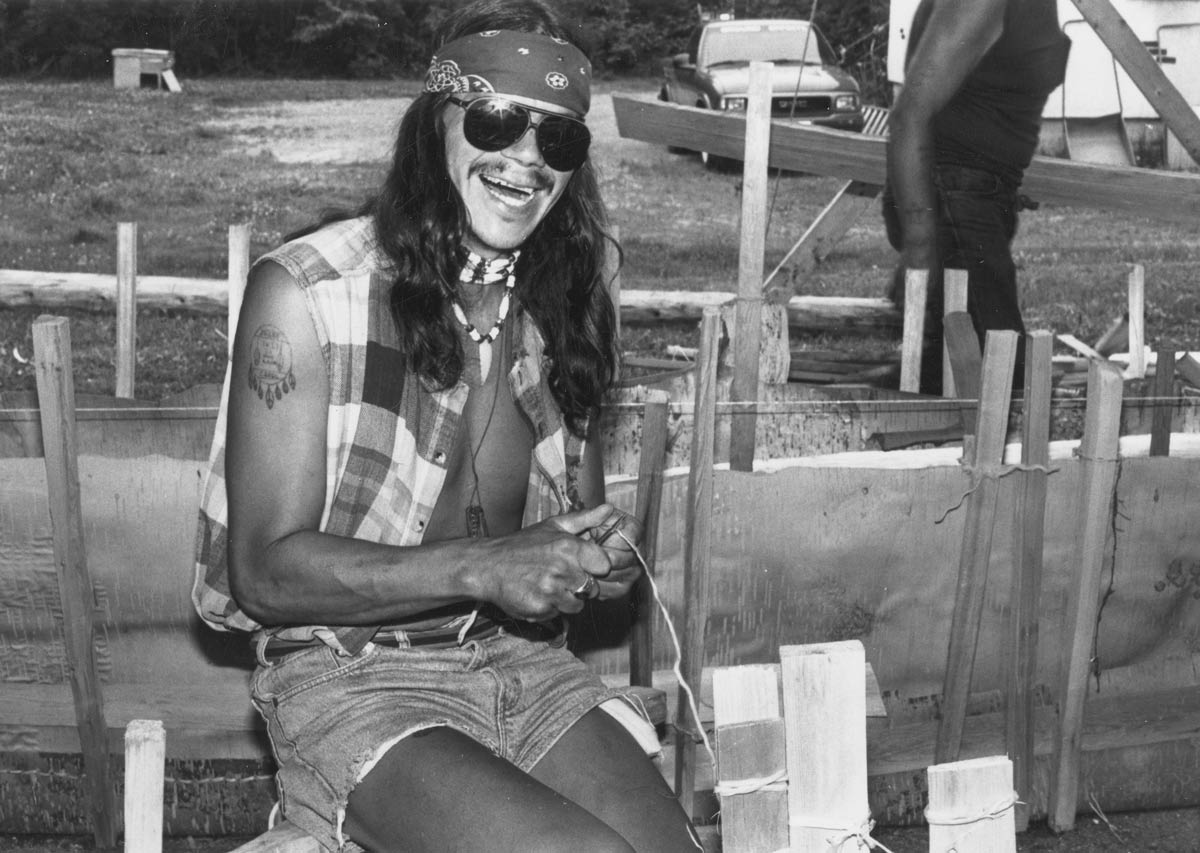

Danny Caplin (Mi’kmaq) splits roots at a traditional birchbark canoe-building workshop hosted by the Ugpi’ganjig (Eel River Bar) Mi’kmaq community. The 16-foot canoe was donated to the NMAI in 1997.

Danny Caplin (Mi’kmaq), Eel River Bar First Nation, New Brunswick, Canada, 1995; Eel River Bar First Nation birchbark canoe photograph and media collection. P26079

Anthropologist and professor Frank Gouldsmith Speck captured this candid photo of a group of Nanticoke school boys playing “bear in ring” during one of his collecting expeditions for the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation. The boy in the center wearing the striped jacket is Roosevelt Perkins.

A group of Naticoke boys. Cheswold, Delaware, 1911–1914; Frank Gouldsmith Speck photograph collection. N01305

Family Reunion

Family portraits are among the thousands of photographs within the Archives Center. Indigenous visitors to the center will sometimes encounter a relative’s image they’ve never seen before. They’ll notice family resemblances, such as the shape of a nose or curl of a smile. When families connect with these images, they often share personal, family, and community knowledge. These stories become part of the archives and are preserved in the image record for future generations.

This photo of a Yup’ik mother with her children was taken by Leuman Waugh, a dentist and photography enthusiast, during one of his research expeditions to study

the dental health of Indigenous communities in Arctic Alaska.

A Yup’ik mother and her two young children in Alaska, 1935–1936. Leuman Maurice Waugh collection, L02288

Sisters Grace and Gail Thorpe (Sac and Fox) were the children of famed athlete Jim Thorpe (Sac and Fox), who, in 1912, was the first Native American to win an Olympic gold medal for the United States.

Grace and Gail Thorpe (Sac and Fox), location unknown, circa 1998.

Grace Thorpe collection, 085_pht_166_009

Coming from a long line of Indigenous artists, generations of the Garcia family have visited the NMAI’s collections and archives over the years. Potter Gloria Garcia (K’apovi [Santa Clara Pueblo]/Pojoaque Pueblo) and artist John D. Garcia (K’apovi [Santa Clara Pueblo]) stand with their young sons, Jason Garcia (Okuu Pin) and John David Garcia Jr. At left are Gloria’s sister Lois Gutierrez and brother-in-law Derek de la Cruz.

K’apovi (Santa Clara Pueblo), New Mexico, 1975

Peter Dechert photographs of Pueblo artists, 440_001_15_00

Joyful Moments

The photographs in the Archives Center tell stories that extend beyond both serious historical events and the borders of the continental United States. From across North, Central and South America as well as the Caribbean, lively images preserve everyday moments of joy, play and friendship. They also show the landscapes and cultures in which Indigenous people grow up.

The frigid temperatures of the Canadian Arctic did not stop these Baffin Island Inuit boys from enjoying their snowy surroundings.

Four boys (Baffin Island Inuit), Padloping Island, Canada, 1950.

Warren Buxton photograph collection, S04853

This smiling young Chickahominy girl dressed in a formal fur hat and coat proudly holds up her porcelain doll.

Chickahominy girl, Virginia, 1918.

Frank Gouldsmith Speck photograph collection, N12619

Power of Portraits

For Native Americans, the power of who to photograph and how once lay with outsiders. During the 19th century, anthropologists, missionaries and government agents were the ones frequently behind the camera. As technology advanced and cameras became widely available, more and more Indigenous people began photographing their families, neighbors and communities. This self-representation and the choice to share such photographs with others—whether through an archive, social media or professional photography exhibition—are powerful forms of self-determination.

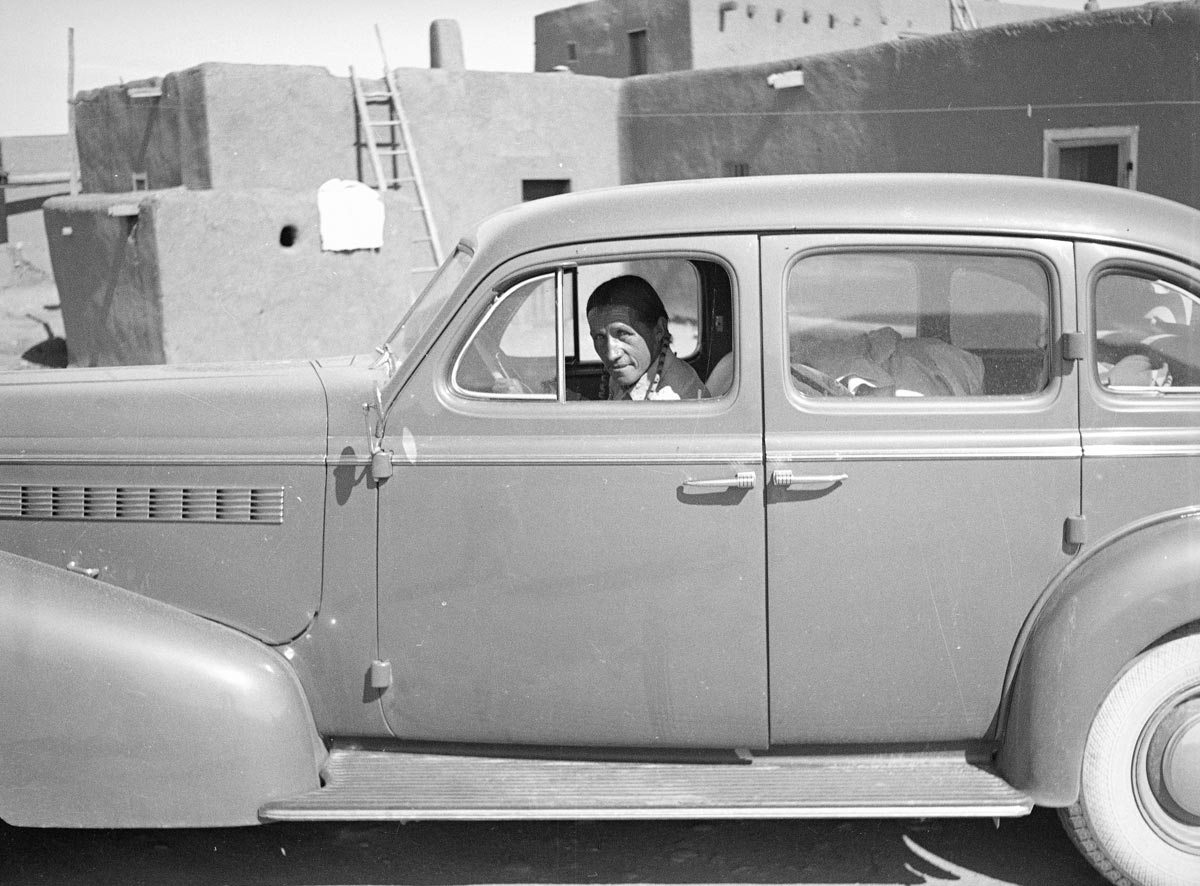

This photo of a Taos Pueblo man sitting in his car with a traditional adobe home in the background captures how the Taos people blended modern conveniences into their culture during the early 20th century.

Taos Pueblo man, Taos, New Mexico, circa 1936–1941; Herbert U. Silleck photographs. N47821

Fred E. Miller took this intimate photo of Points The Gun braiding her hair during his time on the Apsáalooke (Crow) Reservation as a civil service clerk for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He advocated for the rights of the Crow people and was formally adopted into the Crow Nation. He took candid, informal portraits of the community and documented the names and stories of the people during the tribe’s difficult transition to reservation life.

Points The Gun (Apsáalooke [Crow]), Apsáalooke (Crow) Reservation, Montana, circa 1898–1912; Fred E. Miller photograph collection. N13736