In her home in northern New Mexico, Kathleen Wall’s table is covered with a canvas tablecloth, on which are spread a menagerie of paintbrushes, buckets and unpainted figures. She squirts water into a small bowl of paint, stirs it with her brush, then applies dark gray paint to her latest creation, a tower of ceramic figures that seem to dance on top of each other. Between daubs that fill in boot cuffs and stars, she blots the brush on the tablecloth or, sometimes, on her jeans. She tried building a studio space off the side of her house, but working there didn’t feel right. She said, “I learned basically at a kitchen table, and I think that’s why I’m most comfortable here.”

Wall, who is of Jemez Pueblo, Laguna Pueblo and Chippewa heritage, continues a matrilineal tradition of pottery making that she learned from her aunts and mother, acclaimed potter Fannie Loretto. All of them worked in their kitchens, fitting in making ceramics between raising children and feeding their families. So, with three children and a husband, Wall does also.

Wall’s Jemez Pueblo is tucked into a red canyon threaded through northern New Mexico’s Jemez Mountains. Dozens of Jemez villages once spread across these mountains, but since Spanish colonists arrived in the 1500s, the Jemez Pueblo people live in one corridor. The name of their pueblo—pronounced “hay-mess”—carries on the Spanish spelling for a tribe that called itself Hemish. Like many of the other 18 pueblos in New Mexico, this one is known for its ceramic artists.

Wall holds onto the landscape to which she has long felt rooted and the practices kept by Jemez Pueblo potters. Every piece begins with clay she collects from cliffs nearby. Then her work reaches beyond these traditions. During the past three decades, she has branched out from her roots as a ceramic sculptor to experiment with different mediums, including bronze, painting, video and photography. But it is clay that always brings her joy.

“This work here heals me when I’m feeling stressed or hurt or just overwhelmed with life,” she said. “If I sit at this clay table and I just enjoy this clay and its healing properties, I do feel better.”

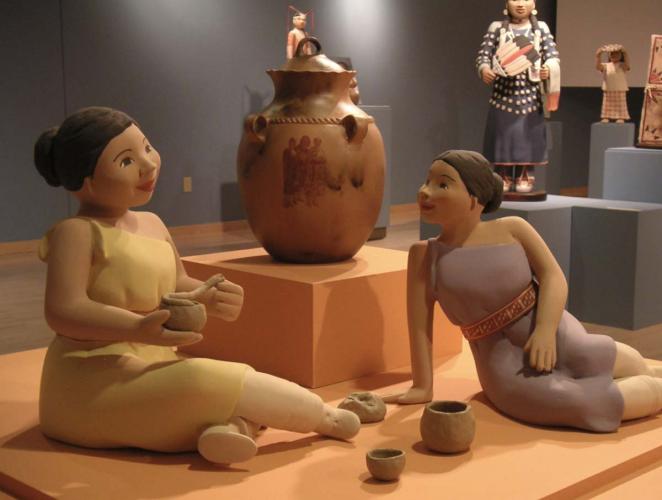

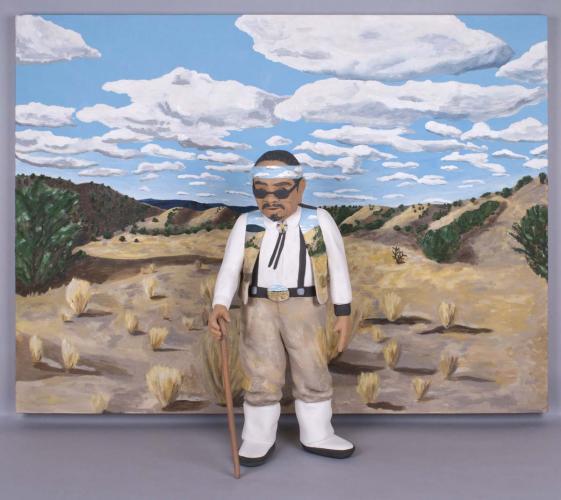

Pottery appears throughout Wall’s home, which was built on land her grandfather gave her so she might always have a place to make her art. A statue she named “Gentle Spirit Holding Pottery and Holding My Culture” sits near a sculpture of an “auntie” she made during a fellowship at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe. (She now calls “Gentle Spirit” her “cover girl” because it was featured on the cover of the Santa Fe Indian Market’s official magazine in 2023.) The auntie stands in front of a topographic painting of her neighborhood that explores how Native people can be so grounded in the place they are from that the two share names, such as that aunt and her neighborhood. A pair of faces she made and her children wore for the Jemez deer dance hang high over the piano, streaked with afternoon light. Storytellers—classic Pueblo figurines of an adult with limbs covered in children—that were made by her mother and aunts line the living room.

Wall still digs clay and the volcanic ash, which is needed to temper pottery against the heat of the kiln, from the same hillsides as her mother and grandmother. Then she wets, dries, sifts and shapes the clay as her mother and aunts taught her. Once the clay is dried, she smooths it with sandpaper and a wet sponge. Finally, she will adorn her figures with patterns that she learned in part by copying a book of designs her grandmother made for an aunt who then tutored Wall.

This knowledge has been priceless to her as an artist. As someone who depends upon her art to survive, she said what might have helped her business the most was what she learned by observing her mother selling her work. As a youth, Wall tagged along while she visited a line of shops, learning how to ask for the buyer, how to talk through pricing and inventory, and, crucially, how to see their responses as a business choice rather than a reflection of her work. “Growing up and having to deal with rejection, it didn’t affect me, I think, because of those upbringings,” she said. “That was vital for me to hang on to this art.”

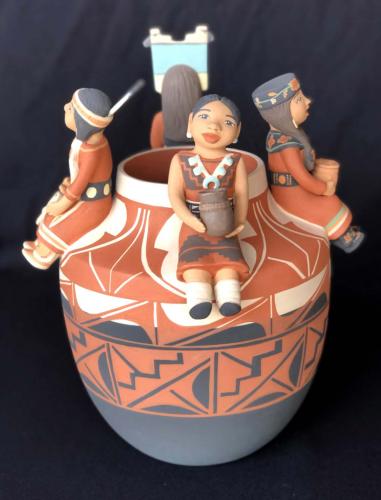

As a young potter, Wall was working on a storyteller figure and the clay dried before she could attach any babies. A price of a work had often depended on the number of babies: a “six-baby storyteller”—a tedious and difficult addition—would cost more than a “three-baby storyteller,” for example. In spite of not being able to attach any, she headed to see one of her repeat buyers anyway. “I walk into the shop, and I have a no-baby storyteller,” she recalls, laughing. “I was quite nervous. But he loved them!”

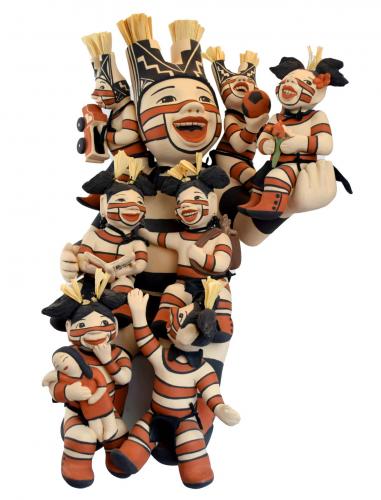

Maybe it was the smile on the artwork that closed the deal, she said. The type of solo figure that has since become her signature is the “Koshare” clown. Koshare is a significant Jemez spiritual figure she frequently depicts with a star in hand, a nod to the traditional Jemez celestial calendar and its requirements of respect, time and reciprocity. People who know her work often call her figures “whimsical” for their jubilant expressions and wide smiles, which she said just effortlessly and unconsciously appear.

She made a piece for the 2024 Santa Fe Indian Market that has four figures, Indigenous women from different tribes representing language, history, culture and traditional knowledge. The Pueblo woman symbolizes history: to her belt is tied a knotted rope that represents Popé, the leader of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt in which the Pueblo tribes united against the Spanish. The Anishinaabe girl holds sweetgrass, which denotes traditional knowledge—in this case, knowing how to gather the grass so some would grow back next year.

“If you’re from Jemez Pueblo, you can almost recognize who she’s sculpting. She just brings to life what’s happening now—wearing your apron because you’re cooking or you’re going to be taking food to the kiva where the men are dancing,” said Mona Perea (Jemez Pueblo/San Ildefonso Pueblo). She is the artist services coordinator for the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts, which runs the Santa Fe Indian Market. “Her work is in living color,” said Perea. “It’s what our people are looking like today and what they’re doing today.”

In 2020, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe recognized Wall with a Living Treasure award, which included the opportunity to feature her work at the museum. That exhibition, entitled “A Place In Clay,” assembled her “Harvesting Tradition” pieces, which explore traditional harvesting, gathering, hunting and growing through a series of hand-built clay figures and acrylic and earth-pigment paintings; a couple of her “Corn Dance” figures, and a trio of “Koshare Stars” figures.

“I was just blown away by the way that she was able to express really complicated ideas in really beautiful and accessible ways,” said Lillia McEnaney, who curated the exhibition. The Koshares had to be there, McEnaney said: “They are just her signature—that is what she kind of burst out onto the scene doing and she’s made such a mark in the contemporary Native artwork through that, and it’s really using those pieces as a way to expand her practice by keeping that foundation.”

Wall is also a member of the Pueblo Pottery Collective, which has more than 60 members from 21 tribal communities. The group co-curated a traveling exhibition “Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery,” which was displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from July 2023 to June 2024.

On an afternoon this past February, Wall was at her table putting the last touches on a free-standing statue of Koshare clowns carefully balanced on one another’s shoulders, reaching for the stars. It had to be balanced. It had to be hollow. And to finish, it would need tiny touches of paint, small flourishes such as corn husks and a separately built basket of stars. That piece, “Koshare Stars, Celestial Bodies,” headed to the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market, where it won second place in the Native clay works division in the juried competition.

“I feel like, if I don’t challenge myself, nobody’s going to challenge me. I could sell a million tiny little clowns—I could make the same thing over and over and over and over, but if I don’t challenge myself, I’m not growing as person. I’m not fulfilled,” she says. “This, for me, is challenging. Wanting to do this piece to begin with has been festering in my head—how am I going to do it?”

Her work strides out into the world through markets such as the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market and Santa Fe Indian Market, where she’s been recognized in the Best of Show and Best of Division categories. She loves that her pieces go into homes, bringing their energy to where people live. But those pieces also give her the gift of time to take on other challenges as an artist. Lately, that has meant pursuing a Master of Fine Arts from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe.

To complete her master’s degree, she is creating video collages that play over clay components. The work visually represents difficult concepts, such as how Indigenous people can feel they must balance Native and non-Native perspectives throughout their lives, or the lingering disconnections and trauma stemming from federal policies such as the Indian Child Welfare Act, which removed American Indian children from their families to be fostered by non-Native families. She tries to make the losses visible, as in paintings of her grandmother and great-grandmother with a traditional Anishinaabe pattern of flowers typically filled with color instead left blank for lost Native identity.

“I’m ever-evolving. .... I hope I always want to do something else,” she says, then gestures back to the sculptures on her table. “But I don’t think I’ll ever veer too far away from this work [in clay].”

McEnaney also worked with Wall on a public art piece in Santa Fe called “Activating Oga Po’ogeh Land Acknowledgement.” That multimedia sculpture paired metal frames with concrete, multicolored ears of corn and video installations depicting community members walking across Oga Po’ogeh, the traditional Tewa name for the village where Santa Fe now stands. She said it was created to speak to the need for land acknowledgments and reparations efforts as well as to heal dispossessions.

“Kathleen is always pushing herself in new directions when she could easily just kind of pass by doing the amazing work she’s always done,” said McEnaney. “She’s always pushing herself to think differently and create differently and make impacts in different areas.” While Wall’s work may center around Jemez clay and pottery, McEnaney said the fact that she is “moving into multimedia work, video work, installation work is really exciting and will hopefully give a lot more recognition and new audiences.”

The film collages may not much resemble the Koshare clown sculptures. But that work returns, as all her work does, to terms she crafted to better express these ideas: inherited belonging and land identity. The video work is as grounded in her homeland as is her pottery. She said, “It’s just that the video installations reference and represent that landscape in other ways, while the pottery comes from the earth itself.”

Wall said her pottery is “my heart-and-hands work. It’s what comes out of me without worrying about everything else, “ she said, “the diaspora and all these things that do consume me sometimes. This kitchen table contains … a joy that illuminates.”